We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Benefits of Prescribing Nature

Guest post by Daphne Miller

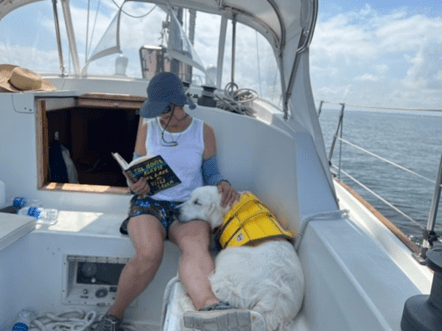

“I have a StairMaster right in my own basement, but honestly it’s been there for years gathering dust and making me feel guilty,” says Miriam, one of my patients. “It wasn’t until I started walking the three-mile trail in the park near my house that I got serious about exercising. I do it now rain or shine. I love the fresh air. The best part is that I get a great workout and don’t even mind sweating.”

At this point, I have heard enough variations on Miriam’s story that I have started to make formal “park prescriptions.” The prescribing instructions are considerably more detailed than ones you might get with a medication; they include the location of a local green space, the name of a specific trail and, when possible, exact mileage.

It turns out I am not alone. I’ve begun hearing about doctors around the country who are medicating their patients with nature in order to prevent (or treat) health problems ranging from heart disease to attention deficit disorder.

Eleanor Kennedy, a cardiologist in Little Rock, helped create a downtown “Medical Mile” with the support of local funders and the U.S. National Park Service’s (NPS) Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program. “If my patients feel that they can get outdoors, they are more likely to be consistent about exercise,” she told me. “Whether you are waddling, walking or running, going out and exercising will help build your confidence, flexibility and adaptability.” And it will also be good for your heart—a particular benefit in Arkansas, where rates of heart disease and stroke, as well as obesity and diabetes, are among the highest in the country.

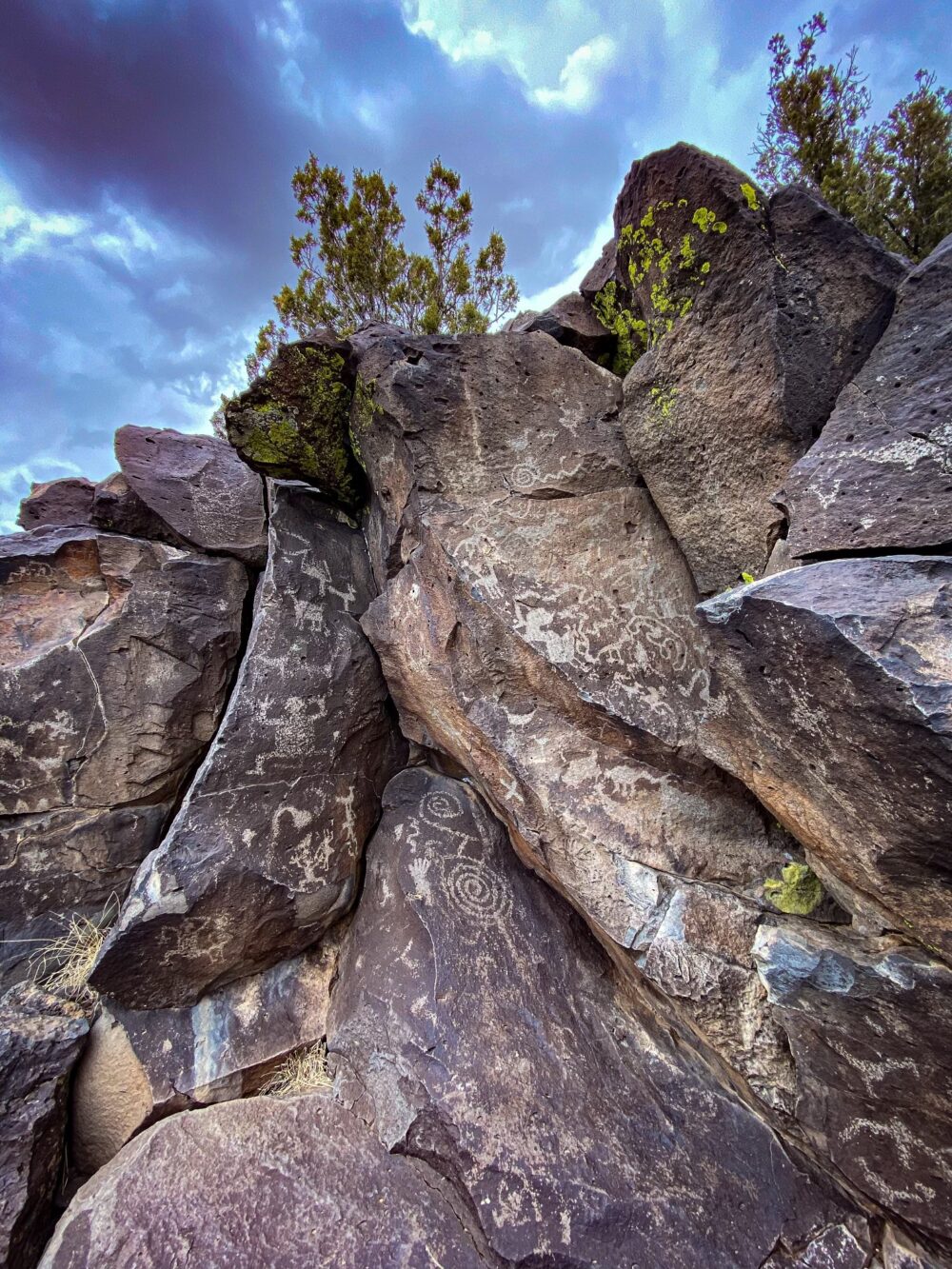

Other physicians, from New Hampshire to Texas, are sending their patients out to wade through streams and walk on beaches and trails. Last year, the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico, launched its Prescription Trails program to target the high rates of diabetes in the community. The program, partially funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, includes a trail guide that physicians can hand to their patients.

“Of course, this is not the only answer to the obesity epidemic,” says Michael Suk, an orthopedic surgeon and former health adviser to NPS, “but it sure is a good start. All these insurance companies focus on prevention, but no one thinks of the free public land resources that we have at our disposal.”

Richard Louv, the author of the best-selling book The Last Child in the Woods who coined the term “nature deficit disorder,” is all for these prescribing patterns. “I think that physicians can do more [to get people out into nature] than any other professional,” he says. Louv’s book and website cite dozens of studies documenting the positive impact that wilderness outings can have on mental and physical health. The fact that the American Academy of Pediatrics invited him to deliver the keynote address at its 2010 annual meeting indicates that the larger medical community is starting to recognize the therapeutic value of time spent in the woods.

Fortunately, the custodians of nature are also on board. Howard Levitt, chief of interpretation and education at Golden Gate National Recreation Area, a NPS site in California, loves the idea of park prescriptions. In the near future, he and his colleagues hope to create a prescription “tool kit” for doctors, possibly in partnership with a large health organization such as Kaiser Permanente. “I see this as a mutually beneficial arrangement,” says Levitt. “We know what parks exist to do and … doctors want to care for their patients.”

Rick Potts, NPS’s chief of conservation and outdoor programs, echoes Levitt’s enthusiasm. “Science is validating,” he says, “what moms have known for generations: Being outside is good for your health.”

Potts, who comes from rural Montana expects support from NPS Director Jonathan Jarvis. “We all see that the role of national parks in the 21st century is evolving. They are becoming more critical to our well-being as a society.” As Potts continued talking, using such terms as “affordable prevention services” and “increasing access,” he sounded more like a government official discussing health reform than one explaining park systems.

In fact, it’s not too much of a stretch to think of our national park system as an integral part of our health care system; the NPS already is offering wellness services that are free and accessible to all, regardless of pre-existing conditions. And according to Suk, the NPS wants to expand that access by supporting public open space developments such as Little Rock’s Medical Mile in communities around the country.

So don’t be surprised if, at your next visit to the doctor, you are handed a trail map and itinerary along with your lab slip. In fact, if you are not offered one, you should demand it. And once you set foot on the trail, how hard should you exercise? I like what Dr. Kennedy tells her patients: “Hard enough that you can still talk in sentences but not in paragraphs.”

Daphne Miller is a family physician and an associate clinical professor at the University of California–San Francisco. Read about the America’s Great Outdoors initiative.