We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

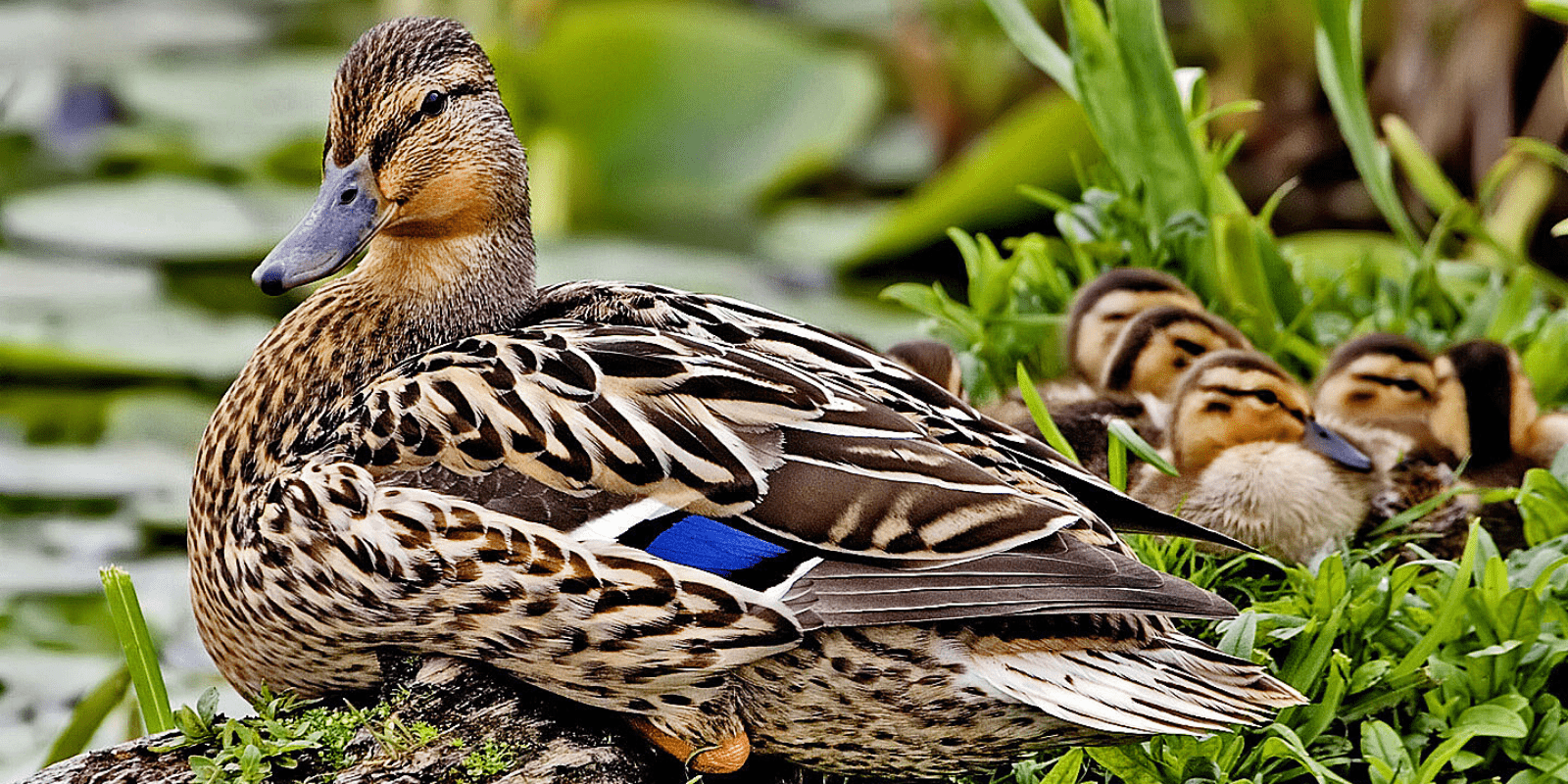

The Slow Revival of America’s Grizzlies

This post was written by Sterling Miller, senior wildlife biologist with the National Wildlife Federation. Before joining NWF, Sterling spent 21 years as a grizzly bear researcher in Alaska. He immobilized 1,000 animals during that time, in an effort to estimate the density of bear populations.

The pattern set by Lewis and Clark of shooting at every bear seen continued for more than 200 years, and by the mid-20th century grizzly bears had been eliminated from 98 percent of their former range south of Canada. Gone were the grizzly bears of Mexico, Arizona, California and the Great Plains. Grizzly bears survived only in Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, and in some of the wild areas along the continental divide between these two parks.

When Congress passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973, grizzly bears were one of the first species selected for protection under the Act, which remains the best law in the world for conserving endangered species. Under the protection of the Endangered Species Act and with the assistance of the states of Montana, Wyoming and Idaho (where grizzly bears still remained), the downward slide in grizzly bear population was reversed. The Yellowstone population was sufficiently secure to be proposed for delisting under the Endangered Species Act and management authority returned from the federal government to the states. Farther north, along the Continental Divide and into Glacier Park, populations also expanded, and within the last few years grizzly bears have once again begun to venture onto the Great Plains along the Missouri River—not too far west from where Lewis and Clark first encountered them.

Grizzly bears are one of the most difficult animals for conservationists to save because they have very low reproductive rates and require a vast area to sustain a viable population. Additionally, grizzly bears can become adept predators on livestock, which are easy prey compared to wild animals like the elk and bison they prey on naturally. Even more problematic, grizzly bears occasionally (although very rarely) attack people, usually because the people are not behaving correctly in grizzly bear country. Lurid tales of such attacks, however infrequent, create an impression of an exceptionally aggressive and dangerous animal—a stories that don’t mesh with the facts. For example, more people are killed and injured in Yellowstone Park by bison than by grizzly bears, and far more people die in the park from traffic accidents and drowning than at the paws of grizzly bears.

Worse, in places like Alaska—which used to have sensible management of grizzly bears and other predators—have become focused on encouraging hunters to kill as many grizzly bears as they can in the hope of reducing populations and thereby increasing the number of moose and caribou available for hunters. The current attitude toward grizzly bears in Alaska is akin to attitudes that existed 100 years ago in the 48 US states and poses a threat to the largest population of grizzly bears in North America.

Grizzly bear populations are out-of-the-woods in a few areas thanks to conservation efforts, but much remains to be done.