We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Deepwater Horizon: The Disaster That Keeps on Harming

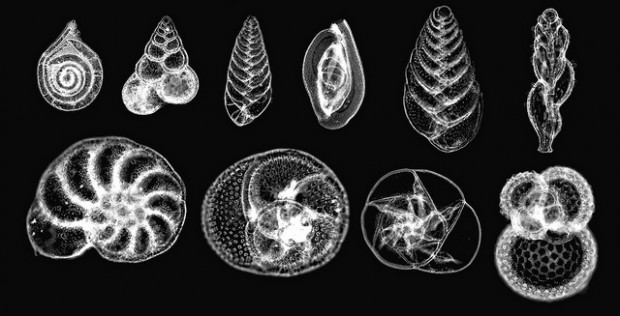

The devastating (but not wholly unexpected) results of a University of South Florida (USF) study suggest the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster is ongoing in the Gulf of Mexico. Foraminifera — microscopic organisms that are the bread and butter of clam and seaworm diets — suffered a massive die-off in oiled areas.

Remember the plume of dispersed oil that stretched from the wellhead and settled in the deep underwater canyon just south of the wellhead? It turns out the foul feature caused an oily sediment blizzard. Analysis of core samples taken from the canyon where the sediment blizzard came to rest showed the record die-off.

As the oil was flowing, David Hollander at USF was one of the first scientists to find that subsea dispersant application led to the plume of oily water. At the time, I was staffing Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL) who sits on the Senate Oceans Subcommittee. Hearing what researchers like Hollander were finding, Sen. Nelson was gravely concerned about the impacts of dispersed oil particles on the Gulf food-web. He filed the Subsea Hydrocarbon Imagery and Planning (SHIP) Act to require the government to track the plume and develop a plan to clean it up. SHIP was never enacted.

Hollander was right to be concerned three years ago. Summarizing the results of the USF study, Hollander says, “Everywhere the plume went, the die-off went.”

Gills serve fish the way lungs serve humans: they allow for oxygen to enter the bloodstream and remove carbon dioxide. In essence, they “breathe.” Healthy functional gill tissue has a uniform, parallel, accordion appearance. Louisiana State University researchers compared the gill tissue of killifish in an oiled marsh to those in an oil-free marsh. The results? The gill tissue from killifish in the oiled marsh was a mangled mess.

Reports that microscopic organisms and bull minnows were harmed by the disaster three years ago suggest there are more impacts to come. It took years after the Exxon Valdez oil disaster for the Pacific herring population to crash. Harm at the bottom of the food-web manifests incrementally. We may not know for years how top predators like tuna and dolphin will fare.

This week, BP began its defense in the Deepwater Horizon trial. One thing is clear: BP would like the American people and the Judge to believe the disaster is over. There is no doubt: BP will present a court case rivaling its public relations case in the court of public opinion. Gulf wildlife aren’t buying it. Neither should Judge Barbier, and neither should we.