We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Is Less Always More?

Is a species more likely to persist in one large habitat? Or, several small habitats?

Last week, while attending the 2015 International Conference on Ecology and Transportation (ICOET), the SLOSS concept appeared again and again – a catalyst for experimental design, modeling query, and just good ol’ fashion debate. Still residing within its comfortable application of addressing habitat fragmentation, the SLOSS concept was referenced in its controversial ability to formulate solutions for restoring wildlife connectivity formerly degraded by transportation networks.

Breaking Up

In the United States, the landscape is fragmented by over 3.9 million miles of public roads. Roads are a major fragmenting force for several species, especially for those with high habitat requirements, like grizzly bears. Roads can drive population fragmentation by simple barrier effects, where high traffic volume may completely discourage a species from crossing – limiting their availability to seek food, water, and shelter. In some cases, roads can completely isolate wildlife populations, which reduces genetic diversity and can threaten a population’s persistence.

Deadly Encounters

In addition to driving habitat fragmentation (no pun intended), roads can also be deadly for both wildlife and humans. Wildlife-vehicle collisions are a big problem on U.S. roads. In 2014, State Farm insurance received over 1.25 million claims resulting from wildlife-vehicle collisions which totaled over $1 billion in vehicle damage.

These collisions are also costly to wildlife. For example, more than half of ocelot mortalities in Texas are due to vehicle collisions, which have decimated the population here to less than 100 individuals.

Providing Connections

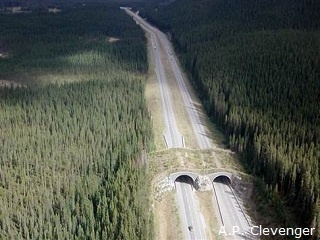

Since France constructed the first wildlife crossing in the 1950s, several European countries have joined in on the use of crossing structures to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions. Wildlife crossings have also become increasingly common in Canada and the U.S. In particular, wildlife crossing overpasses have gained the most recognition given the magnitude of their size and their innovative designs that honor the landscape. In comparison to wildlife underpasses, wildlife overpasses are both larger and costlier. So how do you decide which crossing structure is the best investment?

Return to SLOSS

Here in lies the debate that is SLOSS. Is it better to have a single large wildlife crossing or several small wildlife crossings? After having sat through a variety of presentations at ICOET on the subject of wildlife crossing design and their efficacy for reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions, I began to realize why the SLOSS concept sparks such a debate – there is no universal answer.

Whether your objective is to provide habitat connectivity for multiple species or one species in particular, the design and frequency of wildlife crossing structures needs to be methodically tailored to the given landscape context. Some studies suggest that several small crossing structures can reduce intraspecific predation and the monopolization of crossing structures by territorial species.

Furthermore, as land use demands change to meet the needs of a growing population, the implementation of both types of wildlife crossings will become imperative for safeguarding wildlife.

Making Connections – Both Large and Small

NWF’s Northeastern Regional Center is also busy keeping wildlife on the move. In collaboration with two dozen public and private entities who together form the Staying Connected Initiative, the Northeast Climate Adaptation Team is working to restore habitat connectivity in the Northern Appalachians, which spans 80 million acres across New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and two Canadian provinces.

Images collected in this study will help identify road segments throughout Vermont that are critical for wildlife connectivity. More specifically, the study will find where roads act as a barrier for wildlife movement and how roads actually facilitate the movement of wildlife across habitats. Over time, this work can provide recommendations for the enhancement or replacement of particular culverts that will provide dual benefits – for wildlife connectivity and public safety (i.e. increased flood resiliency and a reduction in wildlife-vehicle collisions).

Through an unprecedented partnership with state and local transportation officials, this work will lead to a reduction of vehicle-wildlife collisions and an increase in habitat connectivity across bisecting highways throughout the Vermont – giving wildlife populations a fighting chance to remain resilient in a rapidly changing climate.