We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Zero Discharge & Virtual Elimination of Toxic Chemicals in the Great Lakes: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

Note: This blog was originally posted on the Canadian Environmental Law Association website on April 12, 2021 and can be accessed at https://cela.ca/guest-blog-zero-discharge-virtual-elimination-of-toxic-chemicals-in-the-great-lakes-yesterday-today-and-tomorrow/

John Jackson is Canadian Co-chair, Toxics-Free Great Lakes Binational Network. Michael Murray is U.S. Co-chair, Toxics-Free Great Lakes Binational Network and Staff Scientist, NWF’s Great Lakes Regional Center.

Yesterday

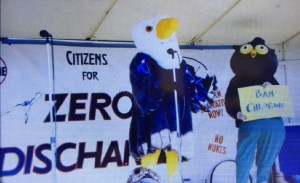

Nearly two thousand people gathered in Windsor, Ontario, in October 1993 for a spirited International Joint Commission (IJC) biennial meeting focused on zero discharge (ZD), virtual elimination (VE), and the sunsetting of the use of certain toxic substances in the Great Lakes basin.

Five hundred of these were grassroots activists from across the Great Lakes and St Lawrence River basin from Duluth to Québec City who rallied in support of the principles of zero discharge and virtual elimination. Hundreds of other attendees (in particular from industry) argued a different view in the “Great Lakes Chlorine-Free Debate” and other events held at the IJC meeting.

This particular debate and the vehemence of particular perspectives throughout the event were the products of several factors:

- Scientific studies and synthesis reports by academic, agency, and nongovernmental organization (NGO) researchers documenting devastating negative impacts on wildlife as a result of persistent toxic substances in the Great Lakes basin, as well as increasing concern about potential risks to people around the Great Lakes, including as summarized in Theo Colborn’s 1990 book Great Lakes, Great Legacy;

- The incorporation of ZD and/or VE goals into legislation in both Canada and the United States, as well as their addition in the revised Canada- U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA) in 1978; and

- Tours of the Great Lakes highlighting these concepts by Greenpeace and Great Lakes United (Greenpeace 1985, 1988 & 1991, Great Lakes United 1986)[1], summarized in the Great Lakes United report “Unfulfilled Promises”), and publications by environmental groups, including “A Prescription for Healthy Great Lakes: Report of the Program for Zero Discharge” (1991) by the National Wildlife Federation and the Canadian Institute for Environmental Law and Policy[2].

The IJC Commissioners stepped forward calling for implementation of programs consistent with the ZD and VE provisions in the Agreement, including through approaches identified by the Virtual Elimination Task Force in 1993.

In biennial reports, the IJC called for a timetable to implement ZD, including a Zero Discharge Demonstration Program for Lake Superior (1990); a timetable to sunset the use of chlorine and chlorine-containing compounds in the industrial sector (1992); and the addressing of radioactive materials under the same principles as other persistent toxic substances (PTS) (1996).

Today

Today, while some progress has been made, governments, industry, NGOs, and others have collectively not adequately followed through on work on toxic chemicals in the Great Lakes consistent with ZD and VE principles. This means that we have not seen the reductions in uses, releases, and environmental levels of these chemicals many envisioned three decades ago. We believe the reasons for this situation include the following:

- Application of ZD and VE principles to a relatively limited number of persistent toxic substances;

- Application of these principles mainly to substances one-by-one, rather than applying them to a whole class of similar substances at the same time;

- Insufficient attention to toxic chemicals that may pose threats for other reasons, such as continual loading into the ecosystem;

- Inadequate implementation in specific programs, even when overarching goals of particular agency commitments reference ZD and VE principles;

- Failure to move beyond a focus on zero discharge from industrial and municipal sources rather than a broader vision of zero use of toxic chemicals, including in products; and

- Failure to explicitly address disproportionate impacts of toxic chemicals in Indigenous communities, communities of color, and low-income communities.

Many of the issues listed here are reflected in longstanding rules and programs implemented by agencies, where in spite of higher-level ZD and VE principles, the actual operative rules and programs allow toxic chemical releases from facilities, as long as amounts are within particular limits, or environmental levels are below particular thresholds. In many cases, new science on individual chemicals shows so-called “safe levels” for fish, wildlife or people are lower than previously thought.

Furthermore, most risk assessment approaches to chemicals have assumed exposures (and effects) associated with individual chemicals, rather than the wide range of toxic chemicals released and present in the environment, chemicals which in some cases can interact with each other or other stresses to cause increased harm.

The combination of the thousands of toxic chemicals in commerce in the two countries (including hundreds of new chemicals entering the market every year), the excessive burden of toxic chemicals already in the Great Lakes environment, and the potential for long-range transport of some chemicals from other regions argues for a reframing of our approach to chemicals management in the Great Lakes basin.

Tomorrow:

To effectively address the ongoing threats from toxic chemicals in the Great Lakes, we will need to draw on the bedrock principles of ZD and VE and identify innovative policies and practices to pursue in the basin.

Such actions are needed to address the plethora of toxic chemical threats in the region, ranging from chemicals long-addressed but still contributing to fish consumption advisories and risks to fish and wildlife (e.g., mercury and PCBs) to many chemicals of emerging concern, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that have long been used but have only in the past decade been the subject of increasing research, monitoring, and policy attention.

Going forward, we believe chemicals policies and activities in the Great Lakes should emphasize several key principles, including the following:

- A more explicit commitment – in practice – by the U.S. and Canadian governments to the zero discharge and virtual elimination principles for addressing toxic chemicals as laid out in the GLWQA;

- More emphasis on considering classes of chemicals for policy (and potentially regulatory) action in both countries, as for example recently argued for PFAS;[3]

- A broader vision of the concept of zero discharge, in particular aiming for virtual elimination of problematic toxic chemicals in uses and processes;

- A more systematic embrace of green chemistry and green engineering principles;

- More aggressive and well-funded implementation of coordinated programs by both the U.S. and Canada through Annex 3 of the GLWQA, with an enhanced emphasis on ZD and VE principles; and

- Explicit efforts to address toxic chemical threats to Indigenous communities, communities of color, and low-income communities.

Next year will mark the 50th Anniversary of the original signing of the GLWQA. Now is the time to draw on historic principles and progress, lessons from current and past work, and new exploration by governments, academic researchers, industry, NGOs and the broader Great Lakes community on innovative approaches to tackle ongoing threats from toxic chemicals, and contribute to restoring and protecting the Great Lakes ecosystem.

[1]Great Lakes United’s Water Quality Task Force. Great Lakes United Unfulfilled Promises. A Citizens’ Review of the International Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (February 1987). https://cela.andornot.com/archives/media/docs/FONDS%20GLU/SERIES_GLU_publications/ITEM_Unfulfilled%20promises%20A%20citizens%20review/Unfulfilled%20promises.pdf

[2] A Prescription for Healthy Great Lakes: Report of the Program for Zero Discharge (February 1991). A joint project of the National Wildlife Federation and Institute for Environmental Law and Policy. https://cela.andornot.com/archives/media/docs/FONDS%20CIELAP/SERIES%20Hazardous%20and%20Solid%20Wastes%20and%20Toxics/SUBSERIES%20Publications/ITEM%20A%20prescription%20for%20healthy%20great%20lakes/A%20presciption%20for%20healthy%20great%20lakes.pdf

[3] Kwiatkowski, C.F., et al. 2020. Scientific basis for managing PFAS as a chemical class, Environ. Sci. Tech. Lett. 7, 8, 532;543. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00255.