We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

12 Things to Know about Mistletoe

Often used as a symbol of renewal because it stays green all winter, mistletoe is famed for its stolen-kisses power. But the plant also is important to wildlife, and it may have critical value for humans, too. Extracts from mistletoe—newly used in Europe to combat colon cancer, the second greatest cause of cancer death in Europe and the Americas—show signs of being more effective against cancer, and less toxic to humans, than standard chemotherapy.

Here are some mistletoe facts that may give you new respect for a plant that, until now, you might have considered as just an excuse to limber up your lips:

- There are 1,300 mistletoe species worldwide. The continental United States and Canada are home to more than 30 species, and Hawaii harbors another six.

- Globally, more than 20 mistletoe species are endangered.

- All mistletoes grow as parasites on the branches of trees and shrubs. The genus name of North America’s oak mistletoe—by far the most common species in the eastern United States—is Phoradendron, Greek for “tree thief.”

- Ancient Anglo-Saxons noticed that mistletoe often grows where birds leave droppings, which is how mistletoe got its name: In Anglo-Saxon, “mistel” means “dung” and “tan” means “twig,” hence, “dung-on-a-twig.”

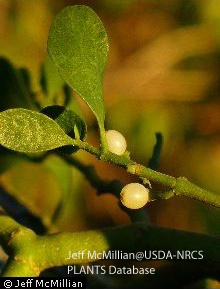

- Mistletoes produce white berries, each containing one sticky seed that can attach to birds and mammals for a ride to new growing sites. The ripe white berries of dwarf mistletoe, native to the western United States and Canada, also can explode, ejecting seeds at an initial average speed of 60 miles per hour and scattering them as far as 50 feet.

- When a mistletoe seed lands on a suitable host, it sends out roots that penetrate the tree and draw on its nutrients and water. Mistletoes also can produce energy through photosynthesis in their green leaves.

- As they mature, mistletoes grow into thick, often rounded masses of branches and stems until they look like baskets, sometimes called “witches’ brooms,” which can reach 5-feet wide and weigh 50 pounds.

- Trees infested with mistletoe die early because of the parasitic growth, producing dead trees useful to nesting birds and mammals. A mistletoe-infested forest may produce three times more cavity-nesting birds than a forest lacking mistletoe.

- A variety of birds nest directly in witches’ brooms, including house wrens, chickadees, mourning doves and pygmy nuthatches. Researchers found that 43 percent of spotted owl nests in one forest were associated with witches’ brooms and that 64 percent of all Cooper’s hawk nests in northeastern Oregon were in mistletoe. Several tree squirrel species also nest in witches’ brooms.

- Three kinds of U.S. butterflies depend on mistletoe for survival: the great purple hairstreak, the thicket hairstreak and the Johnson’s hairstreak. These butterflies lay eggs on mistletoe, and their young eat the leaves. The adults of all three species feed on mistletoe nectar, as do some species of native bees.

- The mistletoe’s white berries are toxic to humans but are favored during autumn and winter—when other foods are scarce—by mammals ranging from deer and elk to squirrels, chipmunks and porcupines. Many bird species, such as robins, chickadees, bluebirds, and mourning doves, also eat the berries.

- The kissing custom may date to at least the 1500s in Europe. It was practiced in the early United States: Washington Irving referred to it in “Christmas Eve,” from his 1820 collection of essays and stories, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. In Irving’s day, each time a couple kissed under a mistletoe sprig, they removed one of the white berries. When the berries were all gone, so was the sprig’s kissin’ power

Happy Holidays!

Like what you read? Please consider making a donation to support our critical conservation work.