We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Brooklyn Students Build Beaver Dams

In December 2017, Diane Corrigan – a wildlife enthusiast and early childhood science teacher at PS 179 in Brooklyn – came upon an article about how a family of beavers were “wreaking havoc” in the Staten Island neighborhood of Richmond. The beavers, allegedly felled 600 trees in the woods around Richmond Creek to build their lodge; they also built a dam in the Creek, which caused water levels to rise and periodically flood streets adjacent to peoples’ homes.

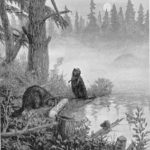

Beaver dams and lodges are protected under the law and it’s illegal to disturb them. So when concerned residents called the city to complain about the beavers, Department of Environmental Protection officials came out during the day and cleared a two-foot hole in the dam. The beavers – known for being skilled engineers – repaired the hole overnight. At the time of this writing, the fate of the Staten Island beavers is unknown.

This human-wildlife conflict with New York State’s official animal piqued Corrigan’s interest. She decided to use it as a teachable moment with her first graders, not only to help students learn about beavers and the many wild animals we share our city with, but to explore an important question: Can wildlife and humans co-exist in densely populated urban areas like NYC? These are critical issues that conservationists are increasingly grappling with.

After watching the video about the Staten Island beavers, Corrigan’s students became concerned about their safety: what would happen if the humans didn’t want them there? Would the beavers have to look for a new place to live? Where would they go if they had to move? Could humans find a way to let them stay in Richmond Creek?

Beaver pond levelers were successfully used in two beaver ponds in Utah to prevent flooding of a Walmart parking lot without disturbing the beavers – a win for wildlife and humans. Could this be tried in Staten Island? These are the kinds of questions that PS 179 Principal, Bernel Connelly, wants Corrigan’s students to explore in the classroom.

“Ultimately, we want to raise generations of children that understand and respect wild animals,” says Corrigan. “But a lot of my students don’t have interactions with animals, so studying them is one way they get to relate to them,” she says. Corrigan happens to be a fan of beavers and has been teaching her students about them for years. This year, she read her first graders books about beavers, used PBS Learning Media resources and a Wild Kratt episode that showcases the elaborate architecture of beaver lodges.

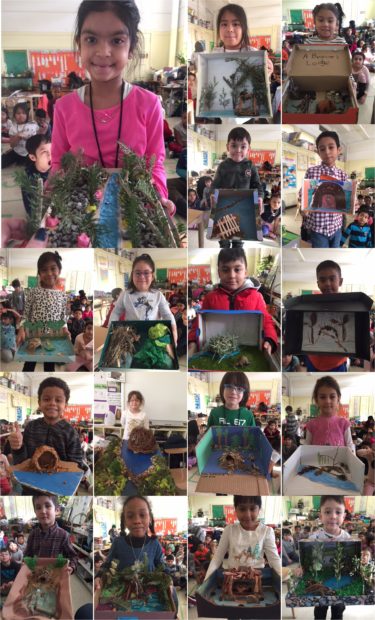

In December 2017, Corrigan gave her students an assignment: If you were a beaver and had to build your home, what would your lodge and dam look like? Corrigan left the assignment open-ended and the results were extraordinary. “The kids really enjoyed the assignment and the parents did too,” says Corrigan.

“People ask me why I teach my first graders about beavers every year. They’re cool and are a lot like humans,” she says. They’re mammals with a good sense of hearing, smell, and touch. They use their hand-like front paws to carry things, spread mud on their lodges, and eat food just like we do. They have been seen rolling up lily pads and eating them like burritos. “On their hind legs beavers can be as tall (4 feet) and weigh as much (70 pounds) as a first grader,” says Corrigan. And although many people consider them a nuisance, they’re actually a keystone species that provides many ecological benefits. Beaver ponds, for example, improve water quality, create habitat for many other species, reduce erosion, and recharge groundwater reserves.

Beavers were abundant in NYC, or New Amsterdam, in the 1600s before European settlers almost wiped them out in the early 1800s as a result of trapping, fur trading, and deforestation. Now encroaching development and human intolerance is making it hard for them to find places to live in NYC.

In January 2018, one of Corrigan’s first graders sent a picture of herself standing in front of an empty beaver enclosure at a zoo during a family trip.

What would happen if beavers disappeared from NYC? A July 2017 report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences offered a devastating statistic: 50% of the individual animals we once shared this Earth with have already disappeared.

So what can we do? The National Wildlife Federation’s California Regional Center has launched a campaign #SaveLACougars, to build the world’s largest wildlife crossing, over the busiest highway in the U.S., to provide safe passage and habitat connectivity for mountain lions and other animals in the highly urbanized landscape near Los Angeles. In NYC, NWF is partnering with teachers like Corrigan to help educate thousands of students about how to protect and preserve pollinators and other wildlife, restore their habitat, and make spaces for them where we live.

In the book Water: A Natural History (1996), Alice Outwater writes that in Native American legends, the beaver helped the Great Spirit create the Earth, make the seas, and fill both with animals and people. We must have reverence for the beavers, and all wild animals, once more, in Staten Island and beyond.