We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Wildlife Could Be The New ‘Homeless, Tempest-Tossed’ As Climate Change Shifts Habitats

According to an article in the online edition of last week’s Science News, climate-change-induced species disruption and environmental displacement is causing major headaches for officials who monitor the movements of non-native invasive wildlife. That in addition to the headaches facing the species themselves.

As climate changes, some environments are becoming hostile to the flora and fauna that long nurtured them. Species that can migrate have begun to move into regions where temperatures and humidity are more hospitable. And that can prove a conundrum for officials charged with halting the invasion of non-native species

In some ways, this resembles the discussion about what makes a plant a ‘weed’ in an urban environment, where actual native plants are usually nowhere to be found.

One problem: What’s native? Species move at will as conditions change. What’s native in one century may be gone five generations later. Newly arrived species, meanwhile, may be environmental refugees.

Questions like this have taken on heightened importance with the dawning realization that some of the consequences of climate change are here now, and changing the idea of what makes a species suitable for a given environment.

National Park Service Director Jon Jarvis:

“Policies that are currently in place view those [immigrants] as exotics,” Jarvis says — invading homesteaders that should, at all costs, be evicted. But such species may be on the move simply “because this is their last refuge,” he points out. “So we have to rethink that policy and how we respond to new species that are coming into our parks.”

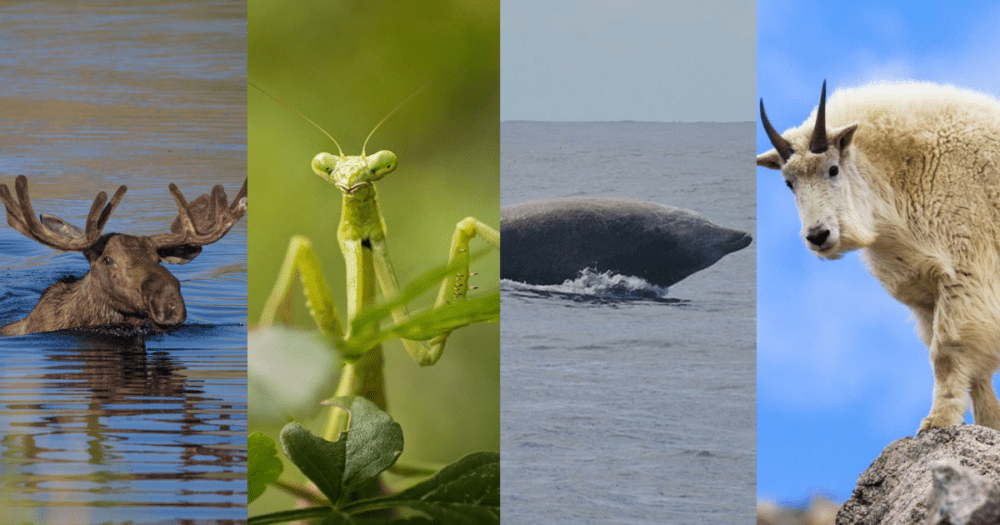

Of course, it is not advisable to simply ‘welcome’ all wild climate refugee. An influx of new, non-native species can be expected to send ripples through an environment in countless ways, many impossible to foresee. Science News points out just a few possible consequences of this under-discussed global warming effect: new species in a habitat could bring “new predators and parasites, altering soil nutrients and porosity, even changing the amount of moisture and sunlight that reaches ground dwellers. And most of these changes can’t be fully anticipated in advance.”

Jarvis was driving down the southern rim of Grand Canyon National Park, a few months ago, when a group of piglike peccaries — also known as javelinas — crossed the road in front of him. The park’s superintendent volunteered to Jarvis that “javelinas didn’t used to be here.” Although an American native, these animals are moving into novel, more northerly locations, Jarvis observes. “And I think this is going to be true for a lot of species.”

Scientists will have to figure out how to deal with these new species, many of which will have no other place to go. Will they go so far as to move or resettle some species to more appropriate habitats, sort of a M.A.S.H. operation for climate-victimized wildlife and plants? If they do, what about species like the giant sequoias, which, as Jarvis says, are “feeling the heat and not liking it” yet obviously not able to be relocated?

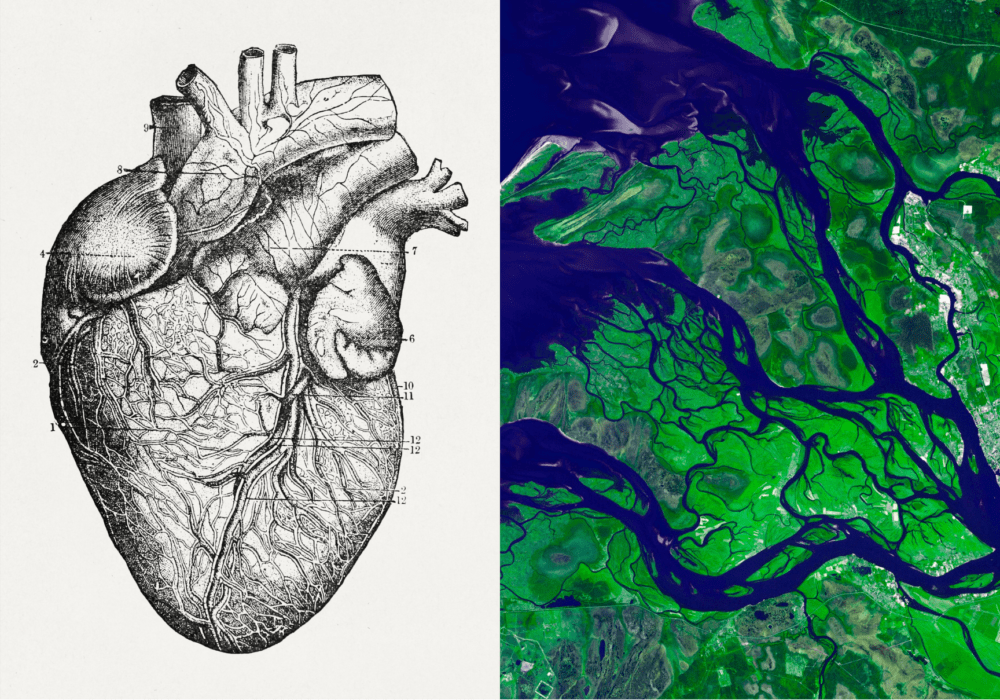

Even those species not expelled from their habitats may find their homestead moving beneath their feet (or roots): A study from Carnegie Institution for Science late last year found global warming is causing climate belts to shift toward the poles and to higher elevations, forcing ecosystems to move by as much as a quarter mile each year to stay in an acceptable temperature area. Sometimes this puts less adaptable plant and animal species in jeopardy.

“Expressed as velocities, climate-change projections connect directly to survival prospects for plants and animals. These are the conditions that will set the stage, whether species move or cope in place,” says study co-author Chris Field, director of the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology.

…

Can the planet’s ecosystems keep up? Plants and animals that can tolerate a wide range of temperatures may not need to move. But for the others, survival becomes a race. After the glaciers of the last Ice Age retreated, forests may have spread northward as quickly as a kilometer a year. But current ecosystems are unlikely to match that feat, the researchers say. Nearly a third of the habitats in the study have velocities higher than even the most optimistic plant migration estimates. Even more problematic is the extensive fragmentation of natural habitats by human development, which will leave many species with “nowhere to go,” regardless of their migration rates.

We’re already pretty familiar with the projected impacts of climate change on human communities—some estimate that so-called ‘climate refugees’ could number more than 150 million over the next 40 years, and many populations are now actively preparing for the moves they may need to make.

Wildlife are a part of this too. Studies earlier this decade found that some animals may lose the ability to adapt quickly to the effects of climate change because those same effects could cause unexpected shifts in their genetic diversity–-“climate change can isolate different groups of animals by affecting the habitats in which they live, in much the same way that the direct destruction of natural land can create ecosystem islands.” In Alaska, shifting climate and loss of tundra could decimate the marmot population and let reed canary grass overwhelm the state in the near future. The pika, furry poster-child for the consequences of worsening climate change, is famously threatened by diminished snowpack and other effects in the American West.

In September, the Fish and Wildlife Service released a new strategic plan (PDF) that calls for federal agencies, states and conservation groups to work together to ramp up research and response to global warming as part of efforts to conserve threatened species and habitat. This is now priority number one–well, close to it, anyway–and it’s been a long time coming.