We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

A Truly Scary Halloween Story: Bats Are In Trouble

Wildlife-Friendly DMV connects wildlife enthusiasts in the District of Columbia, Maryland and Virginia to local wildlife and the National Wildlife Federation. I will share with you the wildlife and nature where I “roam,” and bring to life the stories of people around our region who speak up for wildlife.

Leslie Sturges asked for someone to flip the light switch off. As the room went dark, she flipped on the spotlight attached to her camera. The lens adjusted back and forth, and back—and then came into focus.

Sturges held a bat. A brown bat—a Big Brown bat named Smiley. It was a Friday night in Northern Virginia, where regional bat expert Sturges conducted an educational class on bats at the Walker Nature Education Center.

As Sturges held Smiley, he ate meal worms out of a bowl and she shared with the kids and parents that bats are in trouble because of a disease called white-nose syndrome.

Hands flew into the air.

“What’s white-nose syndrome?” asked a parent.

“White-nose syndrome is a powdery, white fungus that covers a bat’s muzzles during hibernation, making them sick,” said Sturges.

As a wildlife educator, Sturges teaches kids and parents about the importance of bats. As a wildlife protector, she lets kids know they can help protect these creatures spreading the word about white-nose syndrome through Save Lucy the Little Brown Bat campaign.

White-Nose, what?

Sturges, president of Save Lucy the Little Brown Bat campaign, was involved with white-nose syndrome early. She remembers when it first appeared 40 miles outside of Albany, New York in 2006, and no one knew what it was.

This new disease was identified as Geomyces destructans, a cold-loving fungus that is said to have crossed into America from Europe. Bats are susceptible to white-nose syndrome because the fungus breeds in caves or abandoned mines, popular hibernation spots for 46 bat species found in Canada and the United States.

As news about white-nose syndrome developed, Sturges became concerned when biologists and scientists in the Northeast would claim that the public knew about white-nose syndrome. She was more alarmed when policy leaders would tell her that no one really cared about bats.

“I’m out doing education [programs] and lots of people care about bats—kids care about bats,” said Sturges. “But I did realize I had a problem when I asked a room full of 100 people if they had heard of white-nose syndrome and only two people raised their hand.”

Save Lucy the Little Brown Bat

It was that day that Sturges decided she needed to make white-nose syndrome accessible to kids. Save Lucy the Little Brown Bat launched in March 2010. Although Lucy is a fictional bat, she represents all bats that are in trouble because of white-nose syndrome, and provides a story line and pictures for the kids.

“I use Save Lucy as the education platform to raise awareness and let kids feel empowered to do something,” said Sturges. “No one explicitly tells kids that they have a voice—they can write letters to their senators or make posters and educate their family and friends– they can help determine how things are handled in the world.”

Sturges runs the Save Lucy Campaign out of her basement and backyard, where she has a bat rehabilitation facility and flight cage, an outdoor screened-in building where young bats learn to fly. Depending on the month, there are 12-60 orphaned or injured bats in her care. An average day for Sturges includes going to work as the Montgomery County Parks Naturalist and then going to a school or library to do a Save Lucy program where she brings along educational bats.

“I educate people that bats are not Halloween vampires, but important species that keep insects in check by eating up to one-third of their body weight a night,” said Sturges.

And with white-nose syndrome entering its fifth hibernation season (bats enter hibernation October each year), busting Halloween myths about bats is only even half of Sturges battle; it’s finding new ways to use her basement, flying cage, Certified Wildlife Habitat backyard, and Save Lucy campaign to educate all kids and parents that something must be done to protect bats.

“…Champion of nature’s underdogs.”

Since 2006, white-nose syndrome has killed more than a million bats among six species and has spread north to Canada and as far south as Tennessee and North Carolina. As reported by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, in some locations mortality in bat colonies has reached 95 percent.

“I’ve always been a champion of nature’s underdogs,” said Sturges. ““And now more than ever, bats need our help.”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dr_7MKDAr2U[/youtube]

When you arrive at the Save Lucy website, you can take action to help bats, join the Save Lucy Club, record your bat observations and donate to the campaign.

With the Save Lucy Campaign turning two in March, the program has picked up, with an average audience of 50 to 100 people in the region. She shows kids real bats, like Mooch and Smiley, goes outside to listen to bats as they echo-locate, and encourages families to get involved, such as building bat boxes for them to have a safe place to go.

But most importantly, Sturges encourages people to share Lucy’s story.

“All kids and parents can help Lucy by visiting our website and learning what white-nose syndrome is and raise visibility to this problem,” said Sturges. “Because I’ll say it time and time again: when kids care about something, they have the power to change it for the future.”

The clip above is one of Sturges’ bats echo-locating. For additional pictures of the bats in Sturges’ rehabilitation facility click here.

Wildlife-Friendly DMV: Keep it Local, Keep it “Wild”

More Halloween Fun:

- Crows, ravens, owls and vultures: Nature’s creepiest birds?

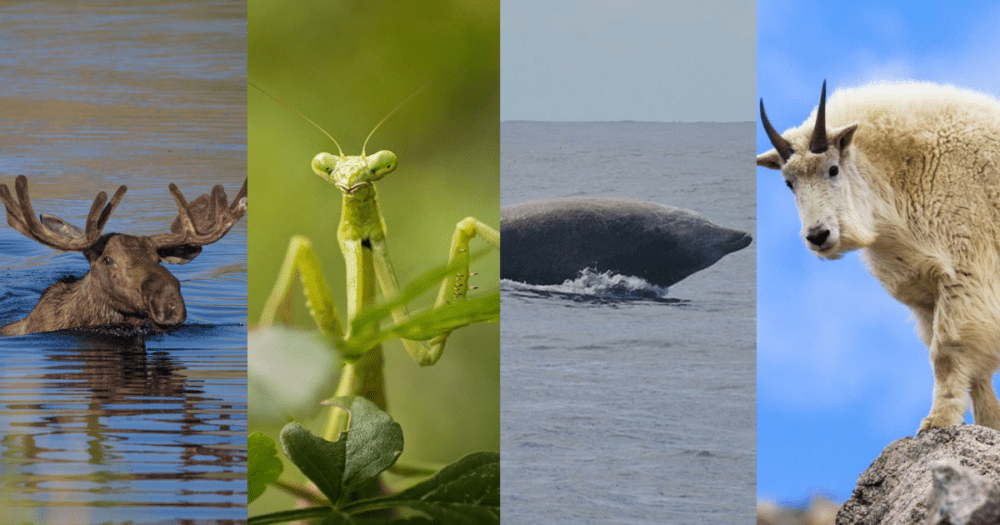

- Get your “scary” animal fix, from vampires to zombie ants.

- Take a peek at a “spooky” animal photo gallery … if you dare!

- Halloween roundup: Get fun outdoor kids’ activities and more.