We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Rebuilding After the BP Oil Spill

This Week in NWF History

Since 1936, the National Wildlife Federation has worked to conserve the nation’s wildlife and wild places. As part of our 80th anniversary celebration, we are recognizing important moments in our history that continue to make an impact today.

Six years ago this week, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded, killing 11 men and spewing millions of gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico for nearly three months. At the time, the National Wildlife Federation staff were on the ground, cataloging the impacts to wildlife and the habitats of the Gulf of Mexico.

Six years later, we are still hard at work. Yesterday, we released a new, interactive report that looks at what the most recent science says about the impacts of the disaster, and how we can restore the Gulf.

Some of the impacts described in the report:

- In the first five years after the disaster, more than three-quarters of pregnant bottlenose dolphins in the oiled areas failed to give birth to a live calf.

- As many as 8.3 billion oysters were lost as a result of the oil spill and response effort. The dramatic reduction in oyster populations imperils the sustainability of the oyster fishery in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

- In 2010, the oil spill killed between two and five trillion larval fish.

- The fate of as much as 30 percent of the oil remains unknown to this day.

Today, we know more about the devastating impacts of oil than ever before — and we also know more about what we can do to restore the Gulf of Mexico. As a result of the various legal settlements with BP and the other oil companies, more than $16 billion dollars will ultimately be available for environmental restoration.

We need to make sure that this money is used wisely on projects that benefit the Gulf as a whole. Coastal Louisiana and the wetlands around the Mississippi River Delta — which were already eroding at an alarming rate pre-spill — received the brunt of the oil that hit the coast. Some marshes and barrier islands still have remnants of BP oil, even six years later.

The money from the settlement means that the very areas that were so badly injured stand a chance to rebound— if we use the settlement money to fund comprehensive, science-based restoration.

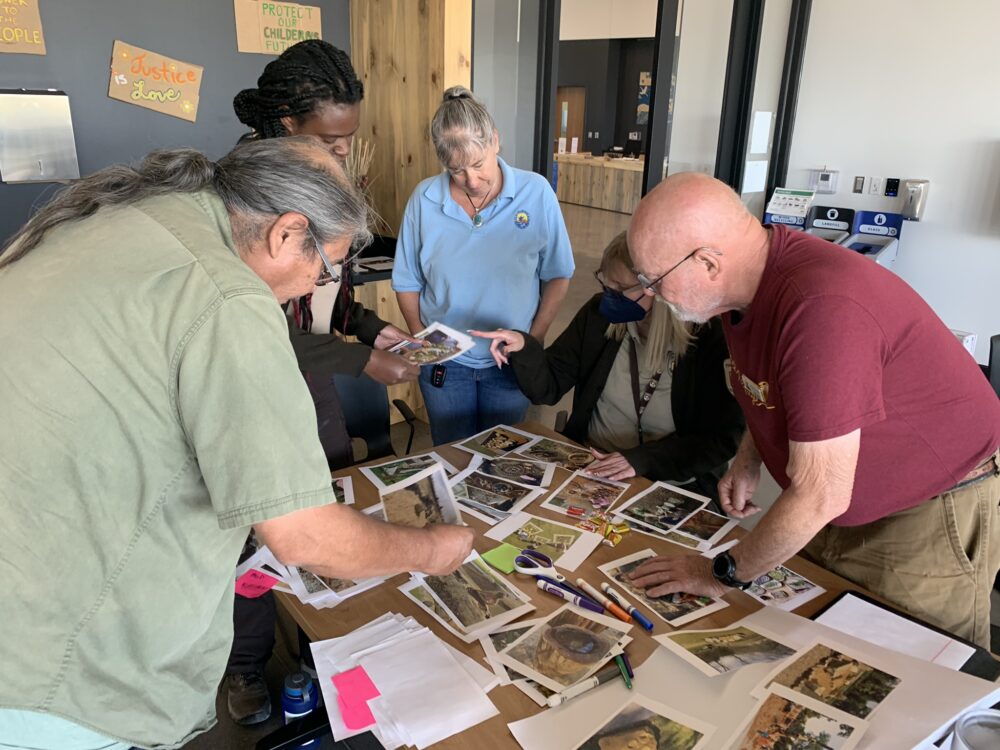

This year, on the eve of the anniversary of the Deepwater Horizon explosion, the National Wildlife Federation and our partners in coastal Louisiana restoration took a tour of Shell Island West, a barrier island restoration project in Louisiana funded by early Natural Resource Damage Assessment funds. This project will restore approximately 600 acres of beach, dune, and marsh habitat. It is part of the larger Barataria Basin Barrier Shoreline restoration project, which will rebuild the eroding barrier islands that separate the ecologically and economically important Barataria Bay estuary from the Gulf of Mexico.

Restoring estuaries like Barataria Bay are key to improving the health of the Gulf of Mexico. Barrier islands serve as a first line of defense, protecting coastal communities from hurricanes and tropical storms. They also form protected areas where freshwater from rivers can mix with the saltier waters of the Gulf, creating nursery areas for many species of wildlife. These protected areas contain a variety of habitats – such as marshes or oyster reefs – that are vital for many different species. Therefore, the Shell Island West project will benefit fish and wildlife that use the barrier island and its beach as well as the marsh on its protected side.

But sadly, in many cases, barrier islands like the Shell Island West are eroding rapidly, leaving both people and wildlife vulnerable.

For our long-term protection, we need to rebuild these critical barrier islands while restoring important habitats like wetlands through sediment diversions and marsh creation. Creating a more natural connection between the Mississippi River and Barataria Bay by building controlled sediment diversions will rebuild and restore wetlands — and it will make projects like the marsh creation and barrier island restoration at Shell Island West more sustainable in the long run.

Take Action

Right now, state and federal leaders are making critical decisions on how to spend these settlement funds that will affect wildlife like the Kemp’s ridley for years to come. Ask them to use the money on smart projects like the one at Shell Island West!