We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Top 10 Winter Warriors

Adapted to Harsh Winter Conditions

Winter is a challenging time for those of us who aren’t so fond of the cold. Every year we break out the heavy coats and scarves to keep warm, but what do animals do?

Let’s take a look a ten “winter warriors” of the animal kingdom with incredible adaptations to help them withstand the unforgiving winter elements.

Polar Bear

Polar bears live in the frigid north where winter temperatures average around -40 °F, but can sometimes drop as low as -92 °F (-69 °C). Thankfully, they have a few unique tricks up their sleeves to combat the cold. To start, those pretty white bears we love so much are not actually white! Polar bear skin is black, which helps them to retain heat by absorbing more of the sun’s rays. Their two layers of fur, on the other hand, are transparent and the longer outer layer is hollow and reflects light, giving them a white appearance. Under their skin is a layer of insulating fat up to 4.5 inches thick!

Wood Frog

Wood frogs literally freeze during the winter months. They stop breathing and their hearts stop beating, but they produce a special glycerol-based substance that acts as antifreeze and prevents ice from forming within their cells. If the water within a cell were to freeze, it would expand and the ice crystals would tear the cell apart, killing the frog. Through this process, nearly 70 percent of the frog’s total body water is converted to ice. This adaptation allows the wood frog to surive even in the Arctic.

Wolverine

Many of the species on this list are increasingly at risk from a changing climate, and the wolverine is no exception. These rare and elusive mammals have dense fur and snowshoe-like paws for walking on deep snow. They live within a “refrigeration zone” in high-altitude, snow-covered peaks. Wolverines also use the snow as a natural refrigerator to store food to get through the late winter and early spring. When temperatures rise and snow melts, they are also at risk of losing high elevation habitats where females make their dens.

Red flat bark beetle

Red flat bark beetles are extremely cold-tolerant. Similar to wood frogs, they produce high levels of glycerol in their blood which keeps the water in their bodies from forming ice crystals. In addition, red flat bark beetles also dehydrate their cells, allowing them to survive in temperatures in which the antifreeze chemicals alone wouldn’t be enough to keep them from freezing. Red flat bark beetle larvae have been recorded surviving in temperatures of -238 °F (-150 °C). That’s one impressive insect!

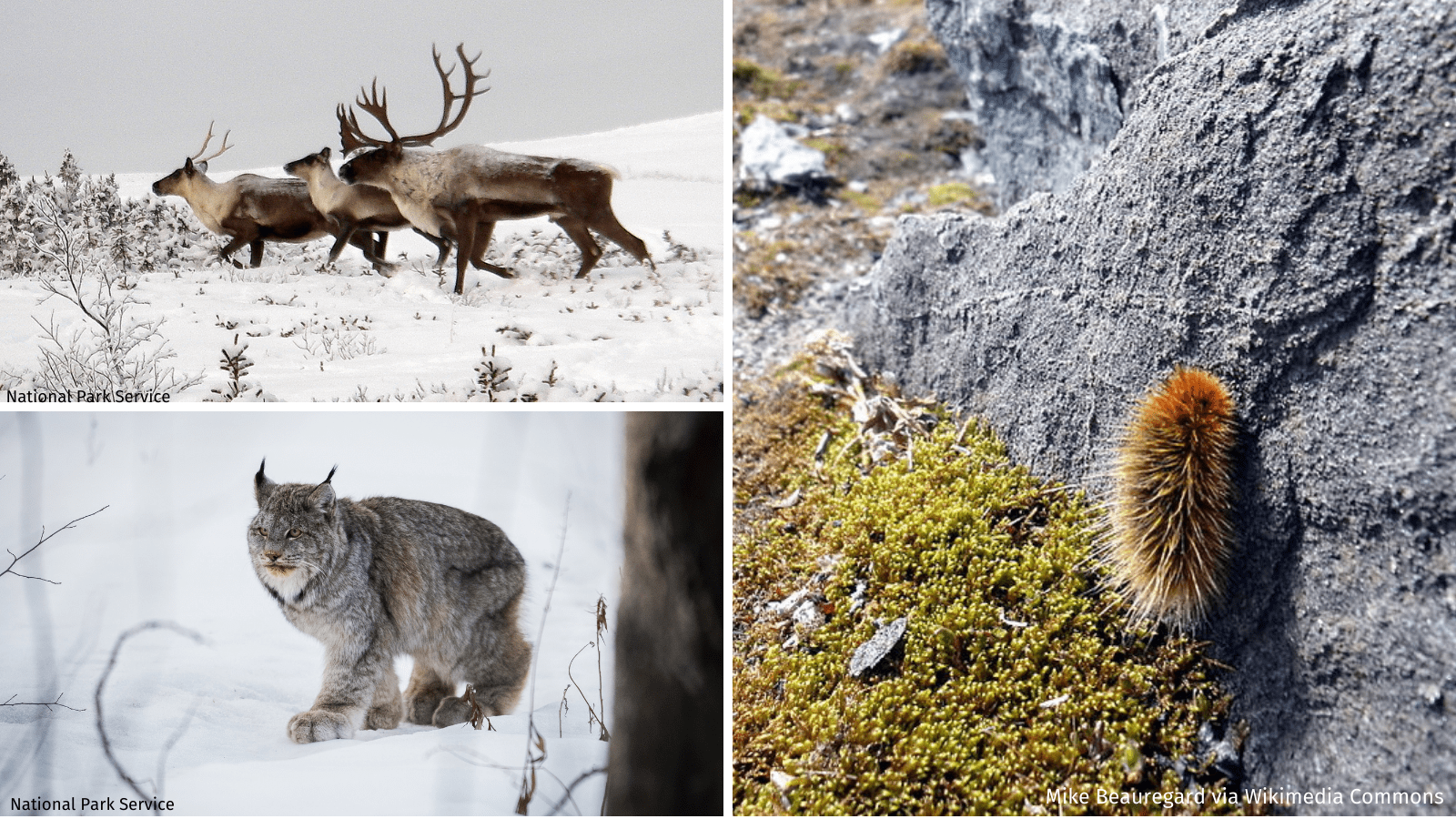

Caribou

Caribou are masters of the tundra. Their hooves are like multi-purpose tools that act as snowshoes for walking, paddles for swimming, and shovels to help them dig for grasses. But even more impressive is the adaptation developed in their eyes, which turn from gold in the summer to blue in the winter to help them see at lower light levels.

Arctic woolly bear moth

The Arctic woolly bear moth lives a unique lifestyle. As caterpillars, they will lie dormant and can withstand temperatures as low as -94°F (−70 °C) in this state. It only gets warmer than that in the Arctic for a short time each year, which means these caterpillars have a limited time to become active and to feed and build up the resources necessary to pupate. This means it may take seven years for a caterpillar to successfully pupate into a moth. The Arctic woolly bear moth caterpillar also expels water from its body to prevent cell death in freezing temperatures.

Black-capped chickadee

Black-capped chickadees are about 5 inches long and weigh barely more than a Sharpie marker. So, how, you might ask, does an animal so small make it through winter in the northern U.S.? Aside from storing food and roosting in small, protective tree cavities, black-capped chickadees have an important biological adaptation: nocturnal hypothermia. During winter nights the chickadees will enter a state of hypothermia, effectively allowing them to lower their body temperature in order to store energy. Black-capped chickadees in northern environments also store more body fat in winter, providing greater insulation from the cold and more fuel for keeping warm. Together, these adaptations make black-capped chickadees tiny but formidable winter warriors.

Lynx

Lynx live in remote northern forests in North America. They have long, thick fur that acts as an insulating winter coat. Their large paws let them walk on the snow with ease and allow them to silently stalk their prey. Lynx populations are dependent upon prey populations — particularly the nimble snowshoe hare — so adaptations like their impressive noses help them thrive.

Arctic fox

Don’t let their cute pointy ears and fluffy tails fool you; arctic foxes are tough! They have incredibly thick fur and a bushy tail that can wrap around them like a scarf, keeping their noses warm. Their short legs, ears, and snout help retain body heat, and the dense fur on the bottom of their paws prevents heat loss through their feet and helps them gain traction on the ice. Arctic foxes use their acute sense of hearing to locate prey deep beneath the snow and refrain from drinking water in the winter as not to lower their core temperature. Instead, they get water through their food.

Tardigrade

There are a number of impressive species on this list, but perhaps none more so than the tardigrade. This extremophile, affectionately called the “water bear” or “moss piglet,” is a microorganism no more than 1.5 mm long that is found in many ecosystems around the world, from mountain tops to rain forests to the deep sea. It can withstand temperatures ranging from -328 °F to 304 °F (-200 °C to 151 °C). It can even survive the vacuum of space!

Tardigrades do this by undergoing a process called cryptobiosis, in which all metabolic activities halt. This would mean certain death for most animals, but not the tardigrade! It has the ability to reverse the cryptobiosis when conditions become more favorable, which is pretty darn cool.

As climate change continues to impact our planet, wildlife are faced with extreme temperatures and changes in historically reliable snowfall. You can help by sending a message to your Senators and Representatives, urging them to support climate-smart policy that benefits both people and wildlife.

SPEAK UP FOR WILDLIFE