We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Annual Bald Eagle Survey Celebrates 40 Years

Bald eagles hold a special place in the pantheon of American wildlife. In addition to being a national symbol, they are also one of our greatest conservation success stories. And for 40 years, volunteers have been aiding in their conservation by participating in the National Midwinter Bald Eagle Survey.

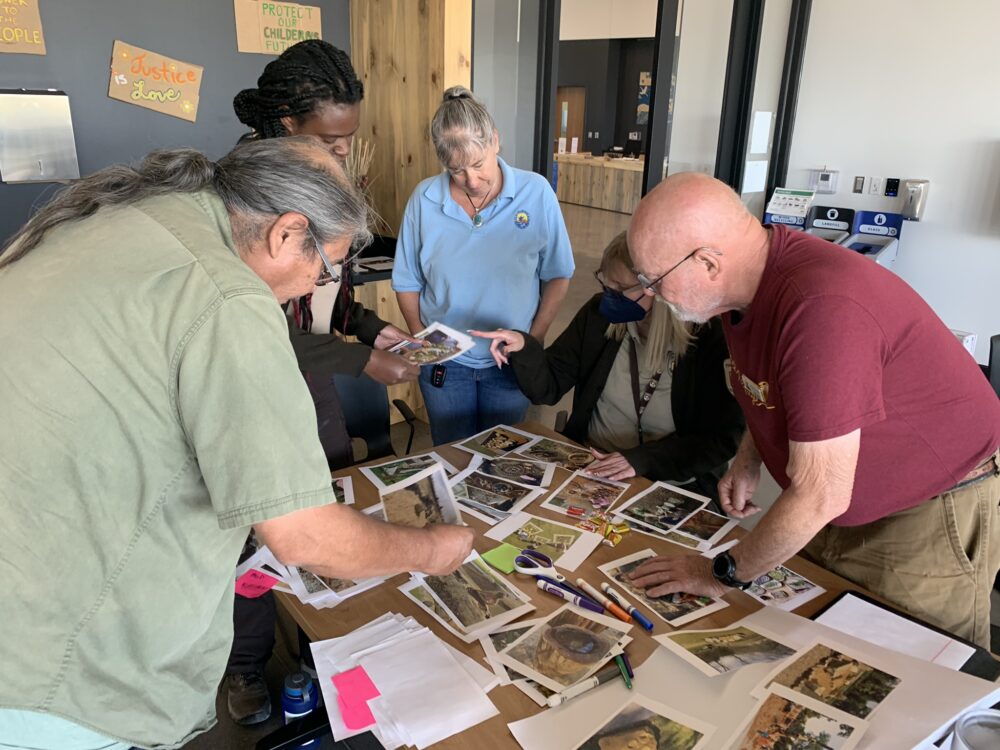

Midwinter Bald Eagle Survey

The National Wildlife Federation led the effort to gather wintering counts of bald eagles from 1979 to 1992. The U.S. Geological Survey took over the survey in 1992, which it coordinates with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Volunteers are conducting this year’s count from January 2 to January 16, with target dates for January 11 and 12.

“Tracking eagle populations, their recovery over the past several decades and increases today has become a joint example of collaborative conservation and coordination across the public sector, the private sector and thousands of committed individuals,” said Kevin Coyle, vice president for education for the National Wildlife Federation.

The government shutdown has affected the U.S. Geological Survey’s Snake River Field Office, which coordinates the survey, but that isn’t preventing the volunteers from collecting the data.

Bald Eagle Conservation History

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates a high of 10,000 nesting pairs when bald eagles were adopted as our national symbol in 1782. By the late 1930s, their populations were on the verge of extinction due to habitat loss, illegal killing, and pesticides. Congress passed the Bald Eagle Protection Act in 1940, their first federal protection.

This temporarily stabilized populations but by 1963, only 417 nesting pairs remained following the widespread use the pesticide DDT after World War II. DDT weakens bald eagle egg shells. Rachel Carson’s 1962 book “Silent Spring” educated the nation about the dangers of pesticides like DDT and the new Environmental Protection Agency banned DDT in 1972.

Bald eagles appeared on the original list under the 1967 Endangered Species Preservation Act and continued under the 1973 Endangered Species Act. The population climbed to 1,188 breeding pairs by 1981 and 4,500 in 1995, when bald eagles where upgraded to threatened throughout the lower 48, as they had been in Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Oregon and Washington since 1978. They were removed from the endangered species list in 2007 with an estimated population of 9,789 breeding pairs.

Reducing Lead Poisoning in Bald Eagles

Bald eagles have recovered but they still face threats from mercury and heavy metals like lead. Lead shot and ammunition fragments found in game carcasses can poison scavenging eagles. The University of Minnesota’s Raptor Center estimates that in the past quarter century, more than 500 eagles it has received have either died from or had to be euthanized due to lead poisoning.

Many hunters are switching to lead-free ammunition to reduce their impact on bald eagles, including copper bullets and steel shot. The National Wildlife Federation’s Minnesota affiliate, Minnesota Conservation Federation, recently advanced a policy resolution calling for a collaborative state-based strategy to reduce lead impacts to wildlife, as well as public education to encourage hunters to use lead alternatives. The National Wildlife Federation also encourages hunters and anglers to use alternatives to lead shot and sinkers.

“As someone who hunts on public lands, I see it as my responsibility to conserve wildlife and leave our public lands better than I found them,” said Aaron Kindle, senior manager of western sporting campaigns for the National Wildlife Federation. “One important way I can do that is by hunting lead-free so that these landscapes and non-target wildlife are not poisoned from my activities.”

Recovering America’s Wildlife Act

Many states also list bald eagles as a species of greatest conservation need under their state wildlife action plans. These lists identify species that require additional conservation actions to keep them off threatened and endangered status. However, these plans often have very little funding for implementation. The Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, introduced in each of the past two legislative terms but not yet passed, would provide funding to states for these plans. The National Wildlife Federation is encouraging Congress to reintroduce and pass the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act.

Bald eagles have had a tremendous journey from the brink of extinction to a recovered and growing population. To keep their populations healthy and growing for another 40 years and more, citizens can encourage their representatives in Congress to pass the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, switch to non-lead alternatives for hunting and fishing, and participate in citizen-science initiatives like the Midwinter Bald Eagle Survey.