We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

PFAS Exposure for People and Wildlife

Following decades of their release into the environment, PFAS are ubiquitous and have been found in wildlife species in every continent. PFAS are commonly referred to as forever chemicals — they don’t break down in their environments. Extensive research has been done to observe the impacts of PFAS exposure on human health, but data gaps and questions remain regarding their impact on ecosystem and wildlife health. How can we better understand the effects on wildlife that share the burden of PFAS contamination and integrate wildlife health into solutions to address chemical pollution?

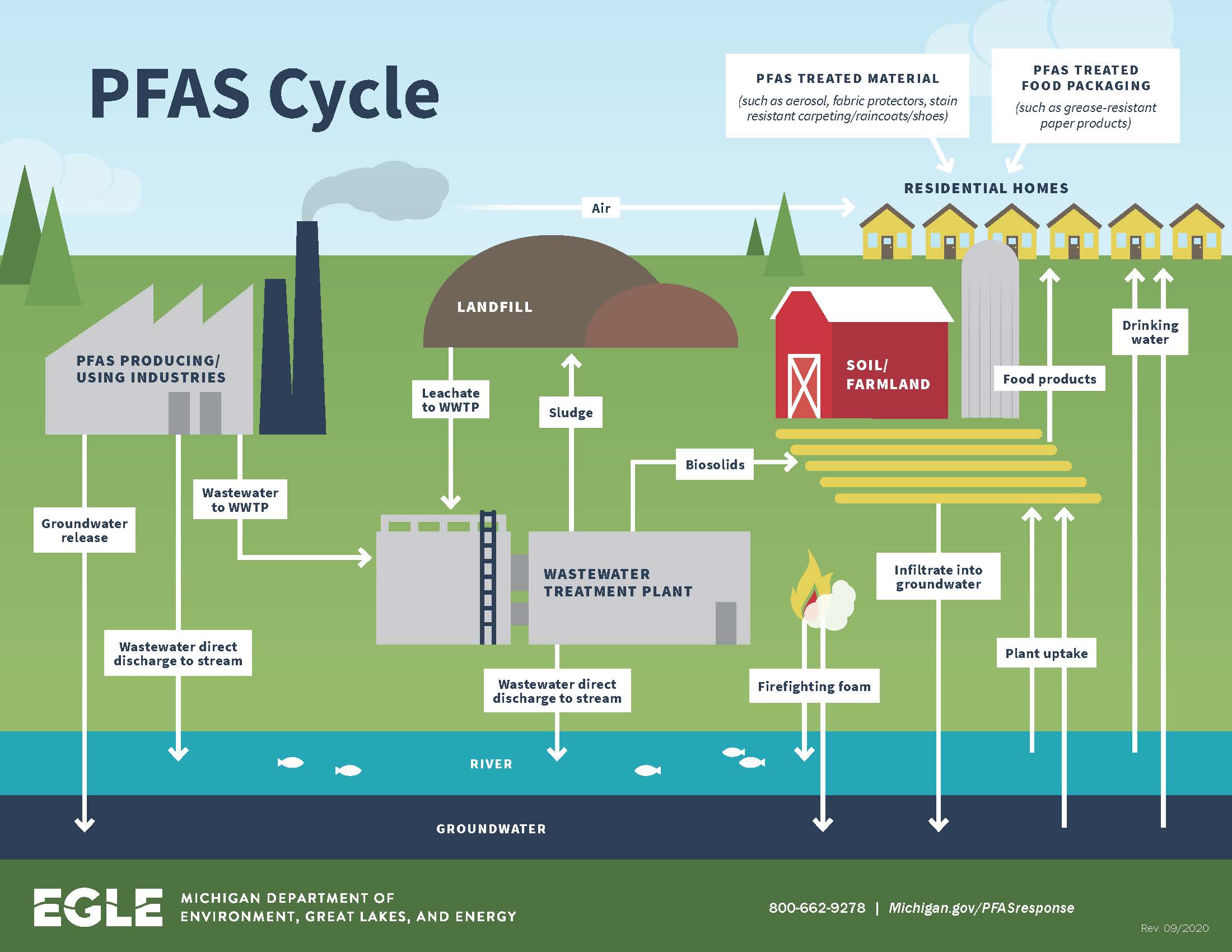

Wildlife are exposed to PFAS through many of the same pathways that impact people — most commonly, proximity to contaminated sites and consumption of water and food resources contaminated with PFAS. Aquatic environments are polluted through point source pollution, including discharge of PFAS-contaminated effluent into waterways, or nonpoint source pollution like runoff contaminated with PFAS, often through the use of Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) for fire suppression or training exercises by fire departments, airports, and military bases.

People and wildlife are also exposed to PFAS through the application of contaminated biosolids, or sewage sludge, onto farmland. Many farmers have applied sewage sludge provided by municipal wastewater treatment plants as a fertilizer, without knowing it has been contaminated by PFAS being processed by the wastewater treatment facility.

Effects of PFAS Pollution on Wildlife

What happens to fish and wildlife when PFAS are introduced into our environment? Oscoda, Michigan, is one of the communities severely impacted by PFAS contamination resulting from the use of AFFF at a nearby air force base. Clark’s Marsh Wildlife Area located in Oscoda is a popular local spot for hunting and fishing. However, deer and fish sampled around Clark’s Marsh have been found with high levels of PFAS in their livers and muscle tissue, and the Michigan departments of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) and Natural Resources (MDNR) have issued Do Not Eat advisories for deer, fish, and other aquatic wildlife hunted within three miles of Clark’s Marsh.

To better understand the extent of PFAS contamination on wildlife in Michigan, the National Wildlife Federation helped organize a coalition of wildlife groups to advocate for additional funding for MDNR to study specific impacted areas and tissue sample wildlife for PFAS.

In addition to these efforts, our partners at the Ecology Center, Huron River Watershed Council, and Friends of the Rogue, coordinated a community-based study along with local anglers to sample 60 fish from 15 sites along the Huron and Rogue rivers. PFAS were detected in every fish sampled.

Fish exposed to PFAS in aquatic environments will hold those chemicals in their bodies and endanger people and wildlife consuming them. The study highlights the dangers that PFAS pose to the wildlife and people that live along and depend upon these waterways, including subsistence anglers, whose food sources and cultural practices have been threatened by chemical pollution.

A recent study by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) aims to explore PFAS impacts on wildlife beyond their role as pathways for human consumption. EWG’s study explores humans as sentinels — or watch guards — for wildlife health and finds that the health impacts that people have experienced due to PFAS exposure such as reduced immune system function and decreased reproductive health are also experienced by wildlife exposed to PFAS. For example, elevated levels of PFAS have been detected in tree swallows, and studies have shown a decrease in egg hatching success and increase in total nest failure in nests with eggs containing PFAS in higher concentrations.

Drawing these connections is key; while studies have been conducted around the health impacts of PFAS contamination on humans, research on wildlife is limited. Increased understanding can encourage increased action and help guide wildlife protection efforts into sound policy changes. EWG’s study elevates the importance of a One Health approach to consider the impacts of chemical pollution to all life and the interconnectedness of human, wildlife, and ecosystem health.

As we all know, these threats do not exist in isolation. The impacts of PFAS pollution on wildlife are compounded by other threats such as habitat loss, and already threatened and endangered species are especially vulnerable to potential health effects of PFAS. Addressing chemical pollution in already degraded and minimized habitat is one part of a larger strategy to address global threats to biodiversity.

Integrating Wildlife Health in PFAS Policy

We recently highlighted policies implemented across the Great Lakes states to protect communities from the impacts of PFAS. These policies, from bans on products containing PFAS to stronger disposal and cleanup regulations, are guided by the people that have experienced exposure to and oftentimes health impacts of PFAS. Policies that protect communities and their drinking water, recreational, and agricultural resources from the impacts of PFAS contamination can also limit the exposure and effects on wildlife.

States like Michigan and Illinois have banned the use of Class B firefighting foam that contains PFAS, protecting nearby waterways and habitats from contaminated runoff, and Minnesota’s comprehensive ban on all products containing unnecessary PFAS will not only keep these harmful chemicals out of homes, but will also limit their pathways into the environment from landfills or facilities that use PFAS in production.

An integrative approach elevating policy that protects both human and wildlife health necessitates strong partnerships with impacted communities. Hunters, anglers, and farmers working within polluted landscapes, communities that have experienced drinking water contamination and health complications, and conservation practitioners that monitor wildlife and habitat health can guide systemic approaches to PFAS contamination that protect habitat, waterways, and the people and wildlife that depend upon a healthy environment.