We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Chemicals of Emerging Concern in the Great Lakes: The Imperative for Additional Action

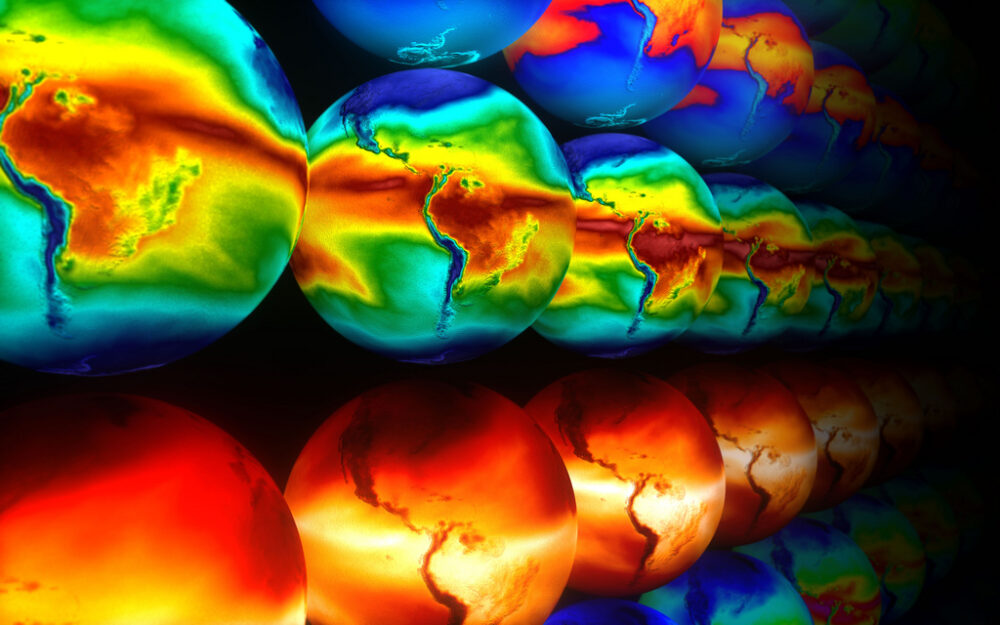

The Great Lakes play a critical role in providing drinking water, transportation, recreation, and livelihoods for the millions of people in the Great Lakes basin. Yet, the health of the Great Lakes is in great danger, as unregulated chemicals of emerging concern (CECs) are being detected more and more frequently in Great Lakes water.

CECs refer to a wide array of chemicals, which include pharmaceuticals, personal care products, household chemicals, and numerous industrial compounds. Many of these chemicals are not regularly included in monitoring programs or widely regulated, but are found to occur in the environment, and in some cases are suspected to pose health threats to humans and wildlife.

As of 2017, findings from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) suggest that CECs are ubiquitous in the Great Lakes Basin. While few studies have investigated CEC occurrence across Great Lakes communities, preliminary evidence and general trends following other environmental pollutants suggest that CECs may disproportionally affect communities of color and low-income communities.

Heightened concern around CECs has led governmental agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), academic researchers, and industry to seek out more information about these threatening chemicals. The Department of Defense recently established a program to identify CECs in 2019, while the EPA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have incorporated CECs into various monitoring programs. Governmental and nonprofit voluntary programs, such as the EPA Green Chemistry program and the U.S. Green Chemistry Institute, have also encouraged researchers and industry to reduce their use of problematic CECs and accelerate research on sustainable chemical alternatives.

While the U.S. has expanded its efforts to address CECs through various programs, these initiatives have not kept up with the pace of chemical development and CEC contamination occurrence. CECs pose a cyclical dilemma, in which a lack of scientific knowledge deters regulatory decision-making and vice versa. Applying the precautionary principle to chemical regulations in the U.S., such as through the Toxic Substance Control Act, would help break this cycle, allowing decision-makers to take precautionary measures when scientific evidence is lacking or limited. More concerted binational coordination between the U.S. and Canada would also help address the risks of CECs in the Great Lakes.

Gaps in current CEC efforts in the Great Lakes region were recently reviewed in a report prepared on behalf of the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) by student researchers from the University of Michigan, in consultation with NWF Great Lakes Staff Scientist Michael Murray. This report suggests that the U.S. and Canada implement the following recommendations to improve the scientific understanding and management of CECs:

- Increase communication and coordination to implement binational CEC monitoring and management programs

- Expand the range of involved stakeholders in the chemicals management process, including citizens, industry, universities, and nonprofits

- Adopt a proactive product lifecycle management approach

- Increase research efforts that focus on better understanding how CECs, CEC breakdown products, and CEC mixtures cycle through a wide range of environmental media and affect humans, fish, and wildlife

- Assess and manage chemicals in classes, rather than individually, to accelerate the decision-making process

- Require industries that heavily rely on CECs, such as the automotive industry, to provide more transparency in sustainability goals

While several isolated efforts have been made to address CECs, it is imperative that stakeholders collaborate to curb contamination by chemicals of emerging concern and protect and restore our Great Lakes.