We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

What’s Happening to Great Lakes Ice?

It’s that time of year again: snow is falling, noses are running, and the Great Lakes are icing. But to what extent are they icing?

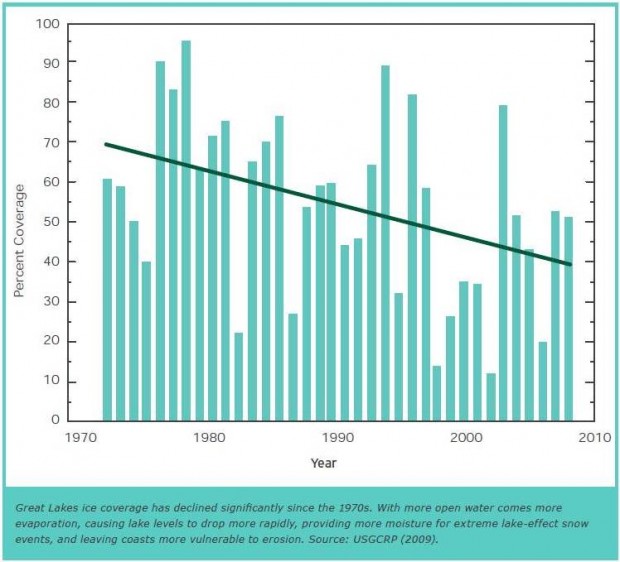

Since ice records began in 1973, Great Lakes ice cover has declined by an average of 30 percent. Records also show that the lakes are icing over later in the winter yet still melting around the same time in the spring.

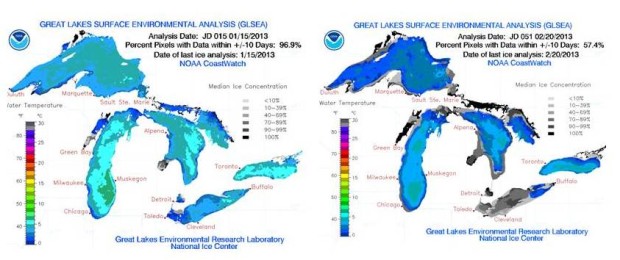

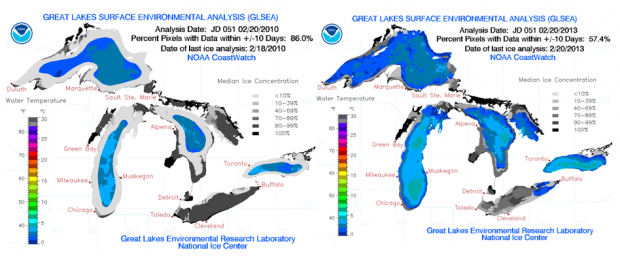

This year is better, but still below normal average. Satellites help us get a better image of how the Great Lakes look from above. These images use composite of data taken from NOAA satellites orbiting the earth’s poles and radar scans of the lakes by the National Ice Center. Here’s what ice cover looked like a month ago versus today. Darker colors like greys and blacks indicate higher ice concentration:

Impact on Wildlife

Wildlife in a Warming World, the latest report by the National Wildlife Federation tells the story of what’s happening to wildlife throughout the U.S. with some specific impacts for the Great Lakes Region.

- Warming in Lake Superior helps the invasive sea lamprey thrive, harming native fish.

- Moose populations in Minnesota have dropped from 4,000 to ~100 since the mid-1980s.

- Many fish species eggs depend on ice cover for protection from dangerous winds or waves. Also, ice cover helps to ward off any bacterial growth that may affect the survival of the fish. Ice fishing – part of a multi-billion dollar fishing industry — is also affected as the ice is a no longer reliable platform to partake in the activity.

- Wetland habitat for many wildlife species is also affected as it depends on stable ice for protection from erosion. Our wetlands in the Great Lakes are vital to bird, turtle, snakes, and other amphibian habitat, protecting the lakes from sediment pollution and cleaning our drinking water.

You can learn more by listening to my radio interview Warming Lake Superior Stresses Wildlife, Observers Say on CBC News Radio.

How does ice cover look from our perspective?

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vZLyT7EuF3c[/youtube]

A neat time lapse video tells the story of this year’s ice cover on Lake Erie. From our shoreline perspective, it looks icy. That is why satellite data and images are increasingly important to tell the bird’s-eye view of the story so we can act before it’s too late.

Solutions

- Federal, state, and tribal governments have developed a comprehensive plan for helping the nation’s fish, wildlife, and plants adapt to climate change. The Administration needs to release and implement this strategy.

- Wildlife and park managers, with the support of the public, need to understand the vulnerability of their resources to climate change and develop forward-looking approaches to manage these changes.

- Management plans for lands and waters need to provide the space needed for wildlife species to shift across the landscape in response to climatic changes.

Second: A transition to cleaner, more secure sources of energy like offshore wind, solar power and next-generation biofuels while avoiding dirty energy choices like coal and tar sands oil will put us on the path to reverse this very alarming trend. We need ice on the Great Lakes, for future generations, for ourselves, for wildlife.