We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Thoughts on A New Normal

This year the Forum tackled the idea of “Living With the New Normal,” a response to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s actual air temperature measurements that show the U.S. yearly normal temperatures are now 0.5 degrees F higher in 1981 to 2010 than they were from 1971 – 2000.

In parts of the Great Lakes region average air temperature increase is closer to 1 degree F.

Using standards established by the World Meteorological Organization, the 30-year normals are used to compare current climate conditions with recent history. Local weathercasters traditionally use normals for comparisons with the day’s weather conditions.

What does this mean for our planet? I tackle these questions through the framework of the three main points of discussion at the Forum.

How is the planet responding to this new normal?

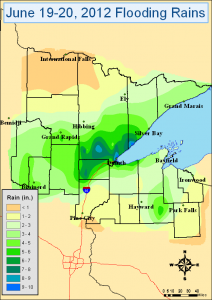

I’ll bring in a Great Lakes example for this one. The most obvious is probably the recent flash flooding in Duluth, Minnesota. Over two days, more than seven inches (some reports are closer to 9 or 10 inches) of rain fell, breaking rainfall records and causing a raging river through the city.

Two-thirds of the zoo was under water, said Holly Henry Marketing Director of the Lake Superior Zoo.

The flooding hit wallets also. Early estimates from the state of Minnesota show at least $100 million in damage.

According to the U.S. Global Change Research Program, the Midwest has already experienced a 37% increase in very heavy precipitation since 1958.

The elements are not matching up. While there’s a problem of too much water in Minnesota, Colorado has a problem of too much fire. Record temperatures in the 100 degrees F and dry conditions have made it very difficult for brave firefighters to do their jobs.

NWF’s own Rocky Mountain Regional Center staff tell more detailed personal accounts of the fires here.

Although we have to be careful to attribute short-term events to climate change, what we do know is that these types of extremes and record-breaking events help us to understand the growing risk that the warming atmosphere induces.

Climate is what you affect, weather is what gets you. – Myles Allen

Read more about the effects of climate change on extreme weather patterns in the U.S. Climate Change Science Program’s report Weather and Climate Extremes in a Changing Climate, Regions of Focus: North America, Hawaii, Caribbean, and U.S. Pacific Islands or in climatologist Heidi Cullen’s book The Weather of the Future.

How are we responding to this new normal?

This work requires lots of relationships across state, tribal and federal lines and across all sectors of the economy to help wildlife survive these changes. NWF is a leader in practicing climate-smart conservation in all approaches to saving wildlife – ecological restoration (especially in the Great Lakes), planning, urban habitats, understanding how and why we are vulnerable and more.

These actions not only save wildlife, but also help our human habitats deal with a new normal. For example, every wetland we restore helps reduce the impact of flooding and water quality pollution to our cities.

How adapting does not mean accepting.

Yet, I still think about those people who emulate the three “wise” monkeys. When will they also respond?

To paraphrase Harvard biologist and famous conservationist, E.O. Wilson, a human response to a message they don’t want to hear is often like this, “First the ridicule, then the outrage, followed by claims of ‘it’s what we’ve been saying for a while.'”

My opinion? It’s really what we’ve been saying for a while.