We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Tribes Cross the Border to Unite for Bison Protection

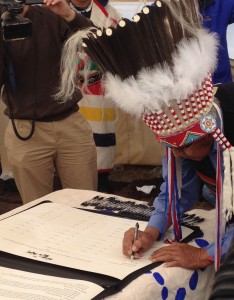

U.S. Tribes and Canadian First Nations Sign First Treaty in Over 150 Years to Restore Bison and Renew Cultural and Spiritual Connections to Buffalo

Yesterday afternoon, I witnessed leaders from U.S. Tribes and Canadian First Nations sign a treaty—the first among them in more than 150 years—to establish an international alliance to restore wild bison. This unprecedented alliance comes on the heels of the restoration of wild bison to the Fort Peck and Fort Belknap Reservations in the last two years after the absence of bison for more than 100 years.

The historic signing of the Medicine Line Northern Tribes Buffalo Treaty occurred on the Blackfeet Nation in Browning, Montana, and brought together members of the Blackfeet Nation, Blood Tribe, Siksika Nation, Piikani Nation, the Assinboine and Gros Ventre Tribes of the Fort Belknap Reservation, the Assinboine and Sioux Tribes of Fort Peck Reservation, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, and the Tsuu T’ina Nation.

The Tribes and First Nations own and manage a vast amount of grassland and prairie habitats-about 6.3 million acres; almost three times the size of Yellowstone National Park – throughout the United States and Canada.

In solidarity, the Tribes’ goal is to achieve ecological restoration of the buffalo on their lands to re-affirm and strengthen ties that formed the basis for traditions thousands of years old. Along with agreeing to work together for bison restoration and grassland conservation on tribal lands, the treaty encourages youth education and cultural restoration among the tribes.

Bison Have Shaped America

For tens of thousands of years, buffalo fundamentally shaped North American prairie ecosystems and linked Native peoples to the land. Following their great slaughter in the 19th Century, buffalo have been largely missing from these lands, resulting in ecological change as well as cultural loss to Native peoples. Settlement of the Great Plains by Euro-Americans resulted in more than a century of habitat fragmentation and disruption and relegated bison to small parcels of protected lands.

To ecologically restore this species, large native prairies that can support far-ranging buffalo are needed. Preserving the few remaining large intact prairies, many of which are tribally managed, is key to restoring bison as wildlife. Leroy Little Bear, a member of the Blood Tribe in Alberta and Professor Emeritus at the University of Lethbridge, explains, “The Initiative is an endeavor on the part of a large group of traditional elders to steer the younger generation back to a path of ecological balance. Sustainability, leaving the land as pristine as possible, and having humans fit themselves into the ecological balance are fundamental to the life-ways of Indian peoples. The buffalo is a major player in this ecological scenario. The near extinction of the buffalo left a major gap. The treaty on buffalo restoration aims to begin to fill that gap and once again partner with the buffalo to bring about cultural and ecological balance.”

Yesterday’s treaty was a landmark event, with the Tribes uniting to bring back to their rightful places on tribal lands and to tribal cultures. In the early 1900s, fewer than 100 wild bison existed in the U.S. Today, bison number in the hundreds of thousands in North America, and are found in state and national parks, wildlife refuges, and on tribal lands, but most reside on private lands as livestock.

Tribes have managed bison herds for years and worked collaboratively to restore wild bison to the Plains. With the transfer of Yellowstone bison to the Fort Peck Reservation in 2012 and to the Fort Belknap Reservation in 2013 – an achievement reached in partnership among the Tribes, National Wildlife Federation, and other organizations – important first steps were taken to return wild bison to western landscapes. Tribal leadership can not only bring bison back to tribal lands, but can also foster bison restoration to large public landscapes across the West. This treaty will foster and expand the process of restoring a vital part of the prairie ecosystem and crucial part of tribal culture and history.