We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

How the Monarch Butterfly Population is Measured

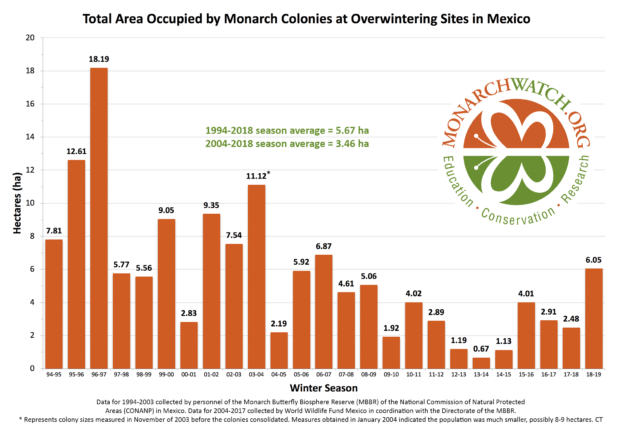

The recent announcement that the overwintering monarch butterfly population has increased 144 percent since last year is great news, but might be a bit confusing. Aren’t monarch butterflies still in trouble? How many actual butterflies are there?

Part of the confusion is because there are two populations of monarchs, the eastern and the western. The eastern population, found east of the Rockies, makes up the vast majority of the North American monarch population and migrates to a specific area in Mexico for the winter, known as the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. The western population is smaller and migrates to a much wider area along the central and southern California coast, collecting in scattered groupings at lower densities than their eastern counterparts.

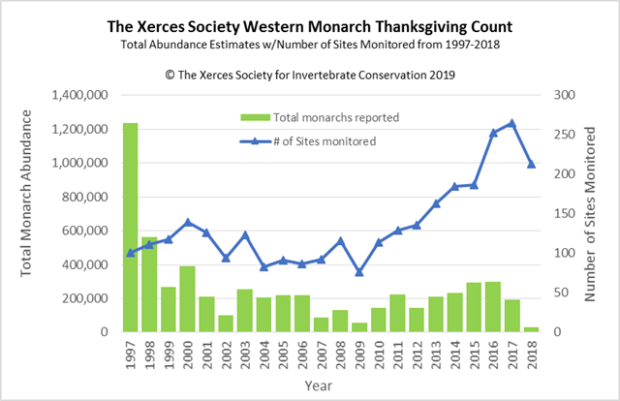

Unfortunately, while the eastern population has seen encouraging growth this year, the western population is not faring as well. The western population continues to plummet and is down over 86 percent since last year and is over 99 percent down from the population high in the 1980s. If you’re confused because you’re hearing seemingly conflicting reports about the monarch population, it’s likely because the news was focusing on different populations.

The way in which the two populations are measured is different too. World Wildlife Fund Mexico and the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve measure the eastern monarch population in hectares, the area the overwintering insects cover, not by individual butterflies. This is in part because there’s not a reliable way to count the individual insects due to the sheer number of butterflies and density in which they gather. Different scientific efforts have estimated that there can be anywhere from 10 and 50 million butterflies per hectare, but that’s such a wide possible range that it’s not particularly useful. Because the eastern monarchs concentrate so tightly at the overwintering grounds in Mexico, measuring the population in hectares gives a reliable evaluation of its year-to-year increase or decrease.

The western population does not concentrate in such tight numbers, and due to this, and the fact that there are far fewer butterflies in the western population overall, it’s possible to estimate the number of individual butterflies during the Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count, a citizen science effort coordinated by Xerces Society.

So the population numbers for the two populations are apples and oranges, one measured in area and one measured in individuals. Both are valid scientific ways to assess the health of the population.

Hopefully, this clears up some of the confusion. Both populations remain in trouble. We all must all continue to keep the effort up to restore habitat by planting native milkweeds and nectar plants, by not spraying pesticides, and encouraging our friends, neighbors and elected officials to get involved.