We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Perspective: Changing Curriculum Connects Faculty with Each Other, Students with Their Environment

Sustainability activity is mushrooming on campuses around the nation-except in one vitally important place: college classrooms. As the recent National Wildlife Federation National Report Card on Sustainability in Higher Education recently revealed, growing numbers of colleges and universities are building sustainability into their mission statements and campus master-plans, and into campus operations and student life. However, faculty and curriculum development on behalf of environmental studies appears to lag behind the progress made in these other campus sectors, and has lost some momentum since 2001.

In the Puget Sound region of Washington State, the Curriculum for the Bioregion initiative, which I direct, is embracing the urgent need for sustainability topics to become an accepted feature of college classes. The goal of the program is to have many more undergraduates encounter sustainability concepts in their courses, particularly in ways that relate to where they live, work, and play. To accomplish that goal, we need to engage large numbers of faculty members in sustainability teaching. And we need to demonstrate how sustainability ideas operate close at hand-on our campuses and in our surrounding communities.

In 2006, our planning phase revealed findings quite similar to those of the 2008 NWF National Report Card. While several campuses in the Puget Sound bioregion were starting to build sustainability goals into planning and campus operations, and while student activists had succeeded getting their student bodies to approve “green tag initiatives” on two campuses, faculty and curriculum development for sustainability education was almost non-existent.

To be sure, many universities had robust majors in place, in environmental studies and natural resources planning and management. But we found that opportunities for all students to gain understanding about environmental protection, environmental justice, or sustainability were remarkably few. For the most part, environmental topics were isolated in environmental science classes; sustainability was being taken up only in some global studies and business classes. Global warming, climate change, and energy-among the most critical topics for today’s students to understand-were startlingly under-represented in the curriculum. We began to realize that thousands of undergraduates could go through their entire college or university career without any exposure at all to sustainability as a lens with which to view the world-or a tool with which to make informed choices in their lives. Not only that, undergraduates might encounter dozens of classes with no reference to the communities where they live or to the idea of citizenship in one’s home place.

Yet, at the same time, on the 18 campuses where we conducted our initial inquiry, we found faculty members from a variety of disciplines who wanted to learn more about the field of sustainability and its core ideas and how to build them into their classes. We also consulted several hundred students. While admitting they had only minimal knowledge of their home bioregion and its issues, these students said they were eager to learn about sustainability, especially how to use this knowledge in their homes and in workplaces.

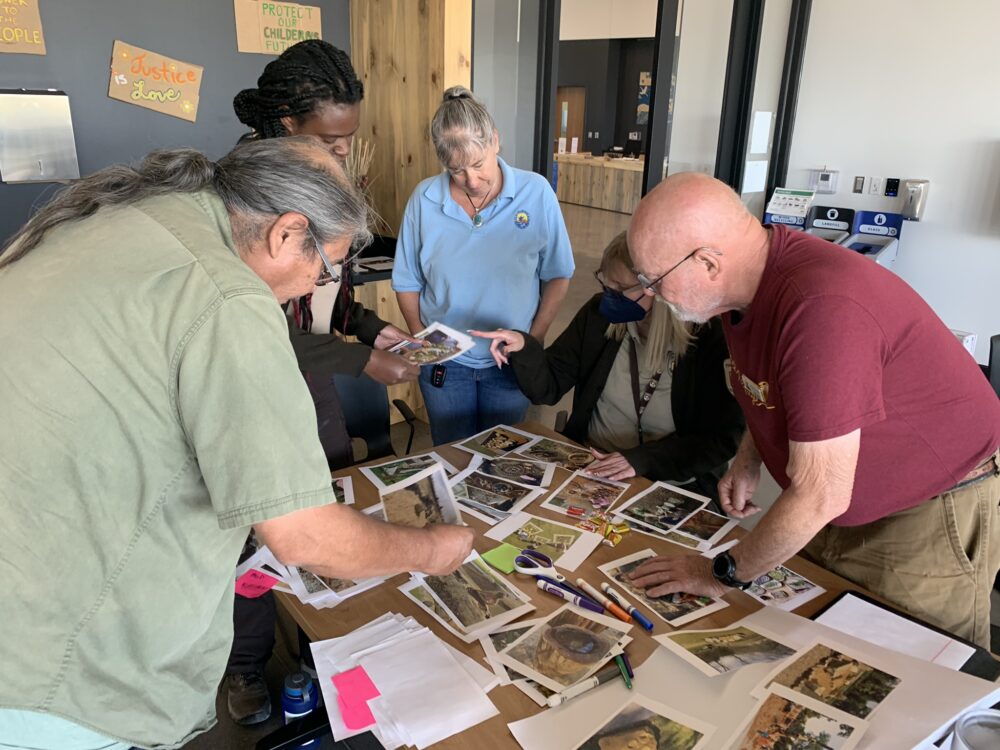

Using that advice, with funding from The Russell Family Foundation, our Curriculum for the Bioregion initiative has been building “faculty learning communities” to work collaboratively on sustainability curriculum development. The goal is not a single course or curriculum but rather a diverse community of faculty members developing an array of engaging learning opportunities across the disciplines. The focus is on introductory courses in the disciplines (the 101-level courses) and on general education classes-and the faculty who teach them. Faculty learning communities are developing teaching-and-learning activities and assignments related to core content or “big ideas” in the disciplines. (“Big ideas” are concepts that matter to faculty in their respective disciplines, but are also ideas powerful enough that students are likely to remember, recognize, and use them for many years.)

The rationale here is, first, that sustainability needs to be taught as core content in a course, not as something uncomfortably patched on as a sidebar or optional topic. Second, the sustainability learning opportunities need to appear in assignments. It is assignments that students take seriously. It is in assignments that students actually work with the material, the ideas, of a course. And it is through assignments that teachers can see how students are learning.

In the 2007-08 academic year, faculty learning communities were created for introductory biology and English composition-classes that typically are among the highest enrollment classes. Twenty faculty members in each community met over a year’s time to develop and share strategies for integrating core ideas and skills in their courses with sustainability contexts and content; each teacher agreed to develop one “teaching-and-learning activity” in depth and write it up for publication on the Washington Center website.

For example, a biology class, studying the fundamentals of energy cycles, researched the energy budgets and environmental implications related to producing different biofuels, asking the question, “How sustainable?” Another introductory biology class, learning the fundamentals of genetic expression, bought small samples of fresh salmon from local markets to sequence the salmon-tissue DNA with lab instrumentation. The DNA analysis revealed which salmon samples were wild Pacific salmon and which ones were farmed Atlantic salmon – offering an opportunity first to check “truth in labeling” and second to explore the worrisome environmental and economic impacts of salmon farming in the Pacific Northwest and to raise questions about sustainable fisheries.

Taking a literary approach, one English class built a “wiki site” about their neighborhoods on the north side of Seattle. Another, while analyzing how writers shape arguments with rhetorical devices, compared Thoreau’s classic 1862 essay “Walking” with contemporary Native American writer Linda Hogan’s 1990 essay of the same name, identifying and comparing the strategies each author used to ask us to form deeper bonds with the natural world.

This fall, the Curriculum for the Bioregion initiative is forming three new faculty learning communities, in the fields of chemistry; philosophy and religious studies; and sociology and anthropology. These communities will each spend the year developing and sharing integrative assignments to teach sustainability in their respective introductory classes. In the coming years, the aspiration is to reach introductory classes in the 15 disciplines for which there is predictably high enrollment.

The emerging curriculum ideas will appear on the Washington Center website as a resource for a broader audience of faculty and to stimulate thinking about developing sustainability literacy. Additional opportunities such as summer faculty institutes and seed grants will make these opportunities more available to faculty-making it possible for them to create communities, share resources and strengthen one another’s professional practice.

The faculty members participating in this initiative come from different places with respect to their interests, their knowledge of this bioregion, and their background in sustainability studies. Yet, when they come together with both diverse perspectives and a spirit of generosity, the mutual support and learning is beyond measure. Our initial evaluations of the program reveal that these faculty members will continue to deepen their interests and capacities for teaching sustainability, especially with locally rooted examples and applications.

We need these kinds of communities of practice to be the trail-blazers for sustainability education. Not only are they providing curricular ideas, they are proving that every academic discipline has important things to say about healthy communities and about our responsibilities to future generations.