We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Let’s Talk Turkey: The History of a Wild Icon in America

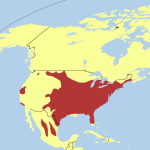

The turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is one of wildlife conservation’s greatest success stories. Unlike the accomplishment of cooking up a delicious stuffed turkey for Thanksgiving, this success story is about wild turkey. In the early 19th Century the wild turkey was reduced to a population of just 30,000. Today, the population numbers about 7 million in North America.

Turkeys are the largest member of the grouse family and they are the second largest wild bird in North America (after Trumpeter swans). Males weigh 11-24 lbs and females 5-12 lbs. Like many sexually dimorphic species, males are selected for maximum sex appeal while females are more sensibly selected to be the right size to glean food from their environment and escape predators. Males can get away with being larger than females as they leave all the rearing of the chicks (poults) to the hens and are not a part of family flocks.

Benjamin Franklin praised the wild turkey and dissed our national bird, the bald eagle, as being “a Bird of bad moral charcter….[who] does not get his living honestly.” I suppose this criticism stems from the fact that smaller birds attack eagles with impunity and eagles steal food from osprey and other birds. Franklin contrasted the bald eagle with the turkey,

“…a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America….Though a little vain and silly, a Bird of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on.”

No doubt Franklin’s perception of turkey’s as “vain” reflects the male bird’s strutting behavior during breeding season. Courtship displays like this, however, are common in many birds and other animals and serve a vital purpose in allowing females to choose the best available mate to father their offspring. Franklin, himself, was known to dress up to impress the ladies and this is no different in intent or function from what many wildlife species, including turkeys, do.

Today, the term “turkey” has come to mean different things including “a stupid, foolish, or inept person.” However, this definition must refer to domestic turkeys and not the the canny wild turkey. While the turkey on your Thanksgiving table is very different from the wild turkey, this success story is one I encourage a share this holiday season.

What wild animal or plant are you thankful for this Thanksgiving? Let us know in the comments below!