We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Highway In the Sky

This time every year, thousands upon thousands of tiny shorebirds depart from their breeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic to begin an 8,000 mile journey — one of the longest migrations of any species in the world. These birds will have spent their summer months nesting in Arctic tundra where they raise their young. The days were long, food was abundant, and they were relatively free from human disturbance. But as fall approaches, the birds must migrate to avoid the brutal winter that blankets the North.

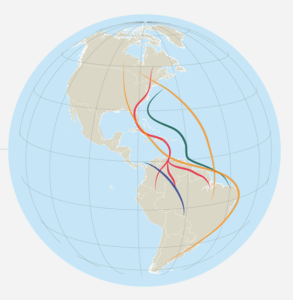

The majority of shorebirds that breed in Alaska and Canada migrate to the beaches of South and Central America. Similar to how humans travel long distances on highways dotted with rest stops for refueling, shorebirds migrate by following their own “highway in the sky.” Biologists use the term “flyway” to describe these discrete paths that birds follow. Here along the East Coast, we have one of the biggest flyways in North America – called the Atlantic Flyway. And just like human highways, the Atlantic Flyway includes numerous rest stops (also called stopover sites) where birds can land to rest and feed. Some of the most important shorebird stopover sites in the Northeast include the Great Marsh and the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge in Massachusetts, the Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge in New Jersey, and the Delaware Bay.

These stopover sites are critical to shorebirds during their migration. Unlike human highways, which seemingly have stops every 15 minutes, there are relatively few stopover sites for birds along the flyway that provide adequate foraging ground and protection from predators. According to experts, the degradation or loss of just one or two stopover sites could have a profound effect on the ability of birds to survive their journey.

Unfortunately, studies have shown that some of these stopover sites are extremely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Major threats include sea level rise, increased storm frequency and severity, and the encroachment of invasive species due to a warming climate. To address these issues, the National Wildlife Federation is partnering with its affiliate, New Jersey Audubon, and others to better understand how we can protect these stopover sites and preserve the unique and important habitats for generations to come. (Find out more about this project here.)

Staff from NWF’s Northeast Regional Center are working hard to protect and restore Massachusetts’ Great Marsh – a vital stopover site for over 67,000 shorebirds. We’ve partnered with Boston University, University of New Hampshire, Massachusetts Audubon, and several other local organizations to restore more than 300 acres of marsh. These efforts will improve overall ecosystem health and, in turn, support shorebird habitat.

The Atlantic Flyway is threatened, as are the thousands of shorebirds that use this highway in the sky. Luckily, efforts are already underway to bolster shorebird populations, improve habitats, and educate and engage the public. However, considering the threats facing birds and their most important stopover sites, there is much more we need to do.

To learn more about the flyway, visit the Atlantic Flyway Shorebird Initiative.