We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Could Your Morning Shower Impact Orangutans in Indonesia?

“Have you showered or brushed your teeth today?”

Hopefully that’s very easy for you to answer. But this simple question serves as an entry-point to a complex topic: orangutan conservation.

At this point, if you’re asking yourself, “What could my hygiene possibly have to do with saving orangutans?!” – I don’t blame you. It’s an odd question to begin a blog about tropical rainforest conservation and new cutting-edge research from the National Wildlife Federation and leading scientists, so let me explain:

You see, wild orangutans live solely in the tropical rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia – specifically on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo – where they are critically endangered due to habitat loss. In Indonesia, huge swaths of forest have been cleared of valuable timber and then burned to make room for oil palm plantations. This not only hurts iconic wildlife like the orangutan, Bornean pygmy elephant, and Sumatran rhino and tiger, but leads to massive amounts of carbon pollution and well-documented human health impacts (how would your lungs feel after spending weeks living right next to a huge campfire?).

What is Palm Oil?

Palm oil – the vegetable oil pressed from the fruit and seeds of the oil palm – is the world’s most widely used vegetable oil, and business has been booming. Much of the developing world uses it as their primary cooking oil, but it’s also used in all sorts of packaged foods, cosmetics, and detergents. But don’t be surprised if you’ve never heard of it. On ingredient lists, it will rarely be listed as “palm oil” outright, but rather as “vegetable oil” (which could also be other oils, like soy), “palmitate,” Elaeis guineensis (the scientific name for the oil palm tree), or “Sodium Lauryl/Laureth Sulfate,” among many other possibilities. Several of these compounds or derivatives help packaged baked goods retain their texture, while others are effective at removing oil and dirt, or helping soaps and shampoos to lather and get sudsy. Now your lightbulb should be switching on. Check the ingredient list on your shampoo, body wash, and toothpaste. Chances are, you’ve used palm oil today . . . perhaps without even knowing it.

Now, you might be thinking that we should just ban palm oil from these products; but unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Palm oil is a very useful commodity given its chemical properties, and oil palm is the most productive crop for producing vegetable oil. This means swapping it for another vegetable oil, like soy or canola, would require vastly larger amounts of land, leading to even greater pressure on tropical forests and savannahs. Instead, we should be looking for palm oil that is produced sustainably. But what does that even mean in practice, and how do we know whether the products we buy contain sustainable palm oil?

Sustainable Palm Oil

Back in 2004, that very question led industry and environmental organizations to come together to form the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (commonly called the “RSPO”). The RSPO has a checklist of requirements for the sustainable production of palm oil, including environmental and social criteria (e.g. no slave labor, which has historically also been a huge problem). Palm oil that meets these requirements gets certified and tracked through the supply chain – from the mill that extracts the oil, to the refinery where it gets converted into different compounds, and ultimately to the manufacturer, where the final product receives an RSPO label. As a result, consumers know what to buy and which brands to support. At least, this is how it was supposed to work in theory (I warned you it was a complex topic, didn’t I?).

Forest Protection

Unfortunately, the RSPO’s requirements, called the “Principles and Criteria” or “P&C” only protect certain types of forest – those that have “High Conservation Values” (like endangered species) or haven’t been disturbed at all – which is problematic because even logged-over forest have lots of value for wildlife. Moreover, determining how to draw the boundaries around these specific forest-types on the ground is messy and subjective work. As a result, when forests were cleared, it was nearly impossible to know if the clearance was permissible under RSPO rules. Many non-governmental organizations attacked the RSPO as being too lax. After years of campaigning and demands from consumers, many companies took on new “zero deforestation” or “deforestation free” commitments beginning in 2013. These were added on top of existing commitments to source RSPO-certified palm oil, based on the perception that RSPO wasn’t actually protecting forests. But the reality is that no one actually knew the impact of sustainability certification on deforestation – until now.

New Study

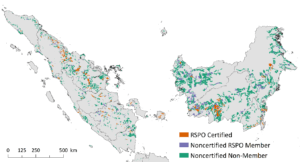

In a brand new cutting-edge analysis published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from several prominent American Universities, NASA (yes, that NASA), and the National Wildlife Federation calculated the effect of RSPO certification on deforestation and fire in Indonesia, the largest producer of palm oil in the world.

Here’s the ten-second version of a four-year study:

- We created a new database of oil palm plantation locations in Indonesia;

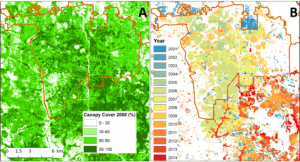

- Using photographs taken from satellites, we looked at the amount of forest left standing after palm oil was grown;

- Then we used statistics to figure out whether the amount of forest remaining differed between plantations certified by the RSPO and those that weren’t;

- Finally, we used econometrics (i.e. extra-fancy statistical analyses) to demonstrate that it was actually the RSPO certification that caused the difference, and not other unforeseen factors.

Study Findings

So what did we find? RSPO certification did significantly reduce deforestation by about a third from what would have happened in its absence. So that’s good news! . . . But (and it’s a big ‘but’), the actual area conserved was surprisingly small (only 8 square miles). That’s smaller than the smallest ‘National Park’ in the U.S. National Park System (Hot Springs National Park in Arkansas is about 360 acres larger), and only about one-tenth the size of the home range of one endangered Bornean elephant. We also found that there was still some impermissible deforestation after certification, and that certification had no impact on the fires or the clearance of carbon- and biodiversity-rich peatlands. This is a big deal because when peat is drained, it becomes like kindling, leading to massive wildfires and “haze” that can choke the entire region of Southeast Asia. As a result of this burning, Indonesia is now one of the world’s largest emitters of carbon pollution!

In the end, we concluded that the RSPO is a mixed bag. Its rules are definitely not sufficient to ensure that palm oil is produced free from deforestation. But it’s important to note that the RSPO does still contain many other worthwhile and important elements of sustainability (such as limiting dangerous pesticide use). Rather than scrapping it, we’re fighting to make it more effective.

Fortunately, there is a big window of opportunity. The RSPO is currently reviewing its Principles and Criteria, to be finalized in late 2018, and there are a few simple steps it can take to improve its record on forests and transparency.

Foremost, the RSPO needs to extend its protections to cover all forest types (including secondary forest) and peatlands, and then utilize satellite-based monitoring to determine whether companies are complying. It’s 2017 – there are lots of tools out there to do this reliably and cheaply.

The RSPO also needs to get strict with companies that are expanding on forest frontiers, where active deforestation is happening. Typically, it was the very old plantations which had cleared their forests long ago that got certified, and these should no longer be the focus. Under the rules, to become a member of the RSPO, companies must establish plans to get all of their operations certified according to an agreed-upon timeline (called a time-bound plan). Though rarely followed, it’s about time that the RSPO enforced these plans. Only then will it have truly meaningful conservation benefits for climate and wildlife.

What Can You Do?

- Be a consumer activist! Go to Supply-Change.org to see if your favorite companies are committed to deforestation-free sourcing of palm oil and whether they’ve made any progress.

- Send a message to your favorite retailer, supermarket, or brand via email or on Facebook or Twitter and let them know that you do not want products linked to deforestation from oil palm expansion. If they are RSPO members, ask them to support “no deforestation” in the P&C review process.

By improving the sustainability tools we have, we can all get a little “cleaner” when we shower.

Want to learn more about deforestation-free palm oil, cattle, or soy? Check out the NWF International Wildlife Conservation website, follow us on Twitter and Facebook, or write to us here.