We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

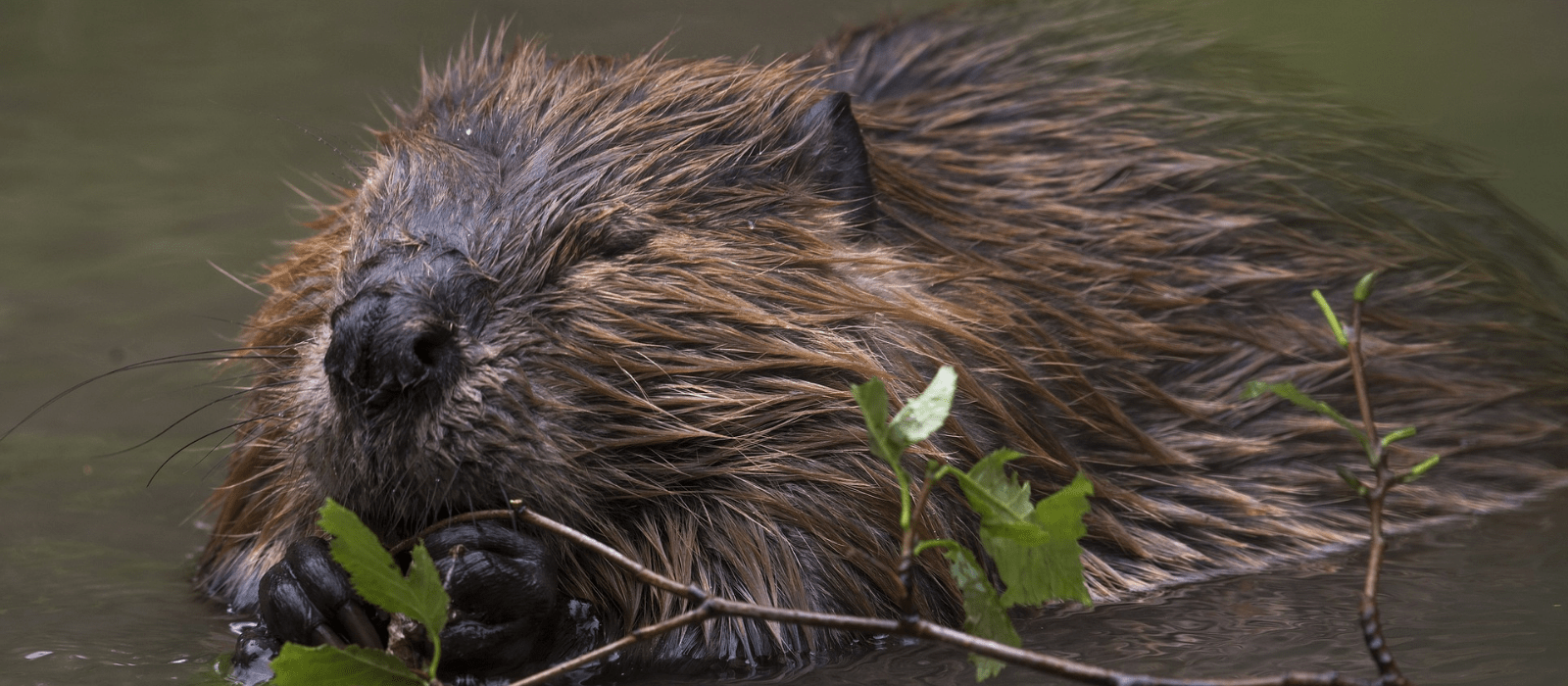

Beavers, Water, and Fire—A New Formula for Success

Low-tech stream restoration works wonders for people and wildlife

In the arid western U.S., water is life. Wet areas—like streamsides, ponds, and meadows—comprise less than 2% of the landscape but are vitally important for wildlife.

Unfortunately, nearly half of these scarce resources are degraded. In the U.S., we collectively spend around $15 billion per year on fixing streams. But we’re hardly scratching the surface.

Conservation partners increasingly work with nature to heal streams. Rather than big, expensive construction equipment, they’re using more cost-effective, low-tech methods. Some of these methods recreate the work that was once performed over large parts of our country by beavers, and simultaneously preparing the landscape for beavers to move back in. These include, but are not limited to:

- Weaving branches through wooden fence posts to mimic beaver dams and create ponds to encourage beavers to recolonize an area

- Placing clumps of woody debris in the channel to slow stream flow and add habitat complexity

- Building stone features that heal incised gullies by reducing erosion and encouraging plants to grow

“The challenge is to find ways of restoring watersheds that are affordable enough to be scaled up to address the scope of degradation,” explains Joe Wheaton, Associate Professor and Fluvial Geomorphologist at Utah State University. “We are trying to use low-tech techniques that will kickstart natural recovery processes with the least amount of money.”

Practitioners sum it up as “let the water do the work” or, in the case of beaver-assisted restoration, “let the rodent do the work.”

“People are really excited after seeing these low-tech structures in action,” says Wheaton. “You can turn a trickle into a pond after one day’s work. It seems like a magic trick, but it’s really just a matter of changing up the timing of how long water sticks around.”

And, importantly, these “emerald refuges” provide valuable wildlife habitat during wildfires, which are burning more frequently and more intensely across western landscapes.

Blue collar conservation

Low-tech restoration approaches are less risky, less expensive, and easier to install than traditional highly-engineered restoration projects.

Since the best practice is to use natural, locally-sourced ingredients to feed the stream, such as branches from recently cut trees, turf and mud, or existing rocks, the materials are often already on site…and free!

“We think of low-tech restoration as ‘blue collar conservation’ because anyone can build these structures,” explains Jeremy Maestas, an ecologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. “That means we get more people involved in conservation, plus we can repair more streams in need.”

“These low-tech projects are often less than one-tenth the cost of traditional restoration projects,” says Wheaton.

How they work for people and wildlife

Streams need a steady “diet” of water, dirt, rocks and wood. These natural elements wash down during floods and slow a stream’s flow, spreading water across the landscape where it can be stored longer between flood events. Each stream’s diet is unique, based on its location, size, and the surrounding climate.

Unfortunately, most of the streams in the western U.S. have been structurally starved of wood (largely from a lack of beaver activity) for the last two centuries. Many of our waterways now flow fast and straight rather than storing water in the valley bottoms and floodplains that create riparian habitat.

By slowing and spreading water, low-tech structures boost soil moisture retention and raise water tables. This, in turn, provides protein-rich forbs and insects for birds, ungulates, and other wildlife. Reconnecting floodplains improves both surface and groundwater availability, and also lessens the erosive energy of floods. Boosting soil moisture and vegetation production keeps restored areas cooler when temperatures soar.

For these reasons, the National Wildlife Federation is exploring opportunities to expand low-tech restoration techniques onto the grasslands of eastern Montana, where late-summer water is in scarce supply for the greater sage-grouse and other species.

Water doesn’t burn

Ranchers have plenty of anecdotal stories of wildlife and livestock flocking to wet, green places when wildfires sweep across the West.

Recent wildfires in the West proved that wet habitat is invaluable as a refuge, and possibly as a firebreak, too: the only remaining green areas amidst miles of scorched rangeland were active beaver ponds that kept the flames at bay.

“Beavers and beaver dam analogs make a lot of sense for mitigating impacts during a fire,” says Wheaton.

It also makes sense to incorporate low-tech stream restoration into post-fire recovery efforts as a tool to protect and improve existing wet habitat. For instance, the Bureau of Land Management is planning to build low-tech structures to accelerate riparian recovery and mitigate mudslides during runoff after the Goose Creek Fire in Utah.

In northeast Nevada where the South Sugarloaf Fire scorched 230,000 acres this summer, the U.S. Forest Service is planning to use low-tech restoration to protect critical habitats that didn’t burn from potential damage during post-fire runoff and debris flows.

Similarly, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game is using low-tech restoration not just to protect critical habitats post-fire, but also to aid in ecosystem recovery on the recent Sharps Fire near Hailey.

In all these examples, the agencies hope to also study the effectiveness of low-tech restoration and to document the vegetation response at restored sites versus unrestored control sites. “If we’re making a difference at a scale that matters, then we should be able to see the positive impacts of low-tech stream restoration from space,” says Maestas.

Especially, he adds, as restored wet places stay greener longer.