We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Suddenly, the Fight to Protect Sage Grouse Becomes Very Real

At 4:15 AM, we stumbled out of our Rock Springs, Wyoming motel rooms to begin our search for sage grouse. We were greeted with several pots of strong coffee in the parking lot by a grinning Aaron Kindle, the senior manager of western sporting campaigns for the National Wildlife Federation. Kindle and David Willms, director of Western Wildlife for NWF, had planned this trip for seven other members of the National Wildlife Federation’s public lands team. The mission was to learn first-hand about the habitat and habits of the Greater Sage-Grouse. Some on the public lands team have been fighting for many years to protect this western bird. Others, just a few months. But only Kindle and Willms had ever actually seen the bird and its elaborate mating ritual up close. This was a chance for the rest to see what all the fuss is about.

We piled into our rental cars and drove in darkness some 90 miles north up highway 191 toward Pinedale. After a couple miles on a bumpy gravel road toward the Wind River Range, we got out to scan the still-gray horizon. Suddenly, there was a flutter of wings as a half-dozen sage grouse flew low overhead and settled down on a snow-covered patch of ground 400 feet away. Sagebrush dominates the landscape, so the male sage grouse carefully chooses a location set apart from sage bushes so that nothing impedes its elaborate courtship prancing.

The breeding grounds of the sage grouse are known as leks and are at the heart of the controversy for sage grouse protection. In 2015, a bipartisan group of western governors, hunters, anglers, conservationists, and oil and gas representatives produced a carefully crafted set of plans designed to protect the imperiled bird, but still allow industry to drill in non-sensitive areas. The plans put a buffer zone to prevent development around the leks to ensure that the birds would continue to mate and thrive, and called for horizontal drilling so that well pads could be built up to a mile away from the sensitive areas.

Once numbering up to 16 million, there are now fewer than 500,000 of these beautiful birds spread across eleven western states. More than one-third are located in Wyoming, which is why we found ourselves near Pinedale bundled in snow pants and layers of fleece on this cold April morning. The mating season typically runs for about five weeks, from March into mid-April. We worried that a late snow storm this year might have put a damper on the sage grouse libido, but as pink rays of sun broke over the mountains, we were thrilled to see some 60 male grouse start to strut their stuff.

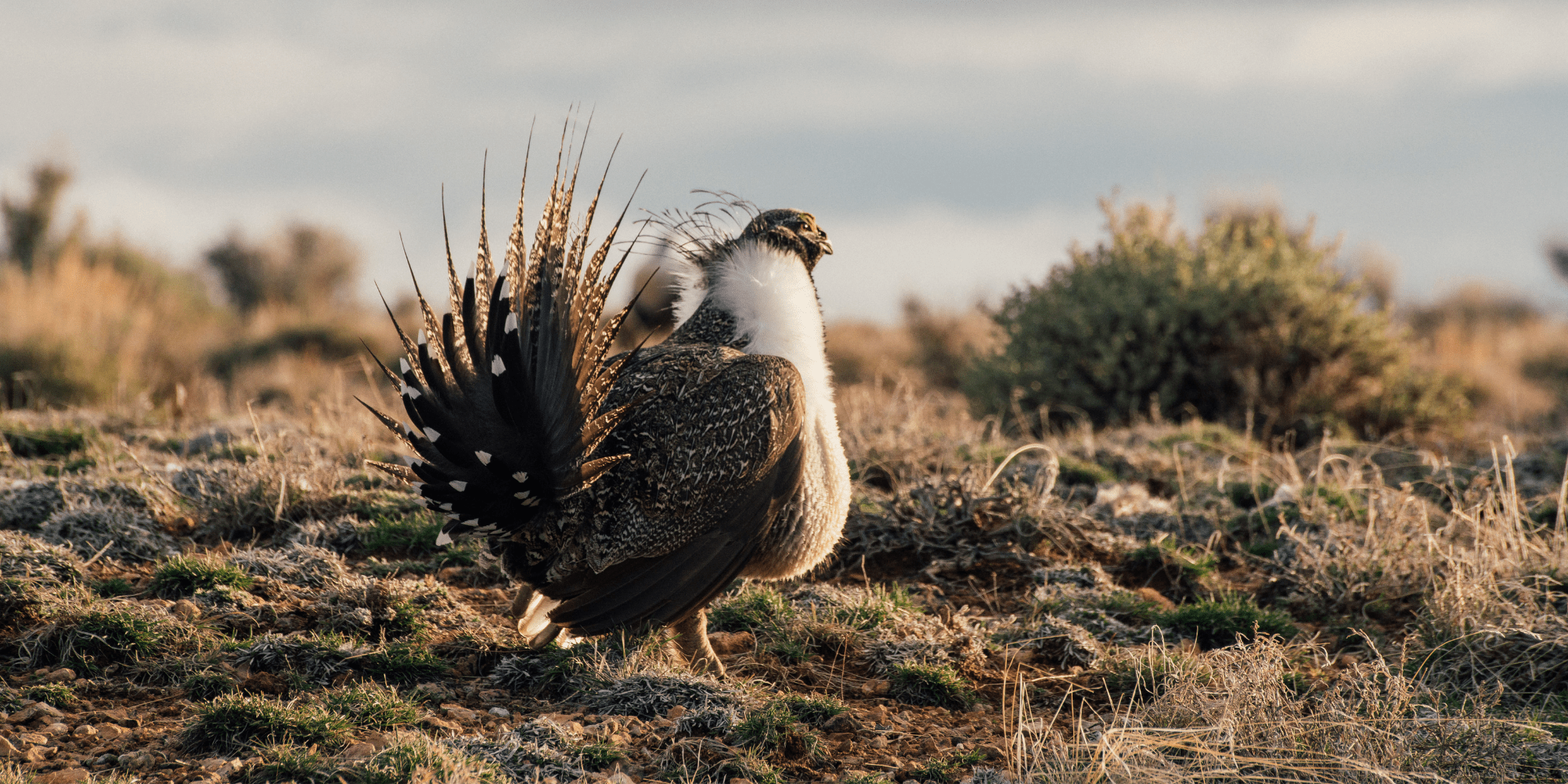

All of us had seen numerous photos and videos of this ancient ritual before. But having it unfold before us like this was simply astonishing. The males are covered with speckled-brown feathers from head to toe, with spiky, white-tipped tail feathers fanning out as they swagger across the lek. Draped around their necks and spilling down their chests is an enormous white plumage that bobbles up and down during the elaborate mating dance. Suddenly two large yellow air sacs emerge from the white neckerchief to propel the distinct mating call to nearby hens: A raspy thin whistle followed by watery gurgling sounds.

Hiding behind a slight ridge and using scopes and binoculars, we were transfixed for two hours, watching the males strut past one another – each trying to outdo the other in catching the attention of the hens. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, usually only one or two males get picked by a majority of the females at a lek. In fact, scientists have recorded a single male sage grouse mating with 37 different females in just 37 minutes. We did not witness such a wondrous (and no doubt exhausting) feat. But we did see how the courtship lasts for just a couple of hours and then the birds disperse until the next day when dance begins again.

Our work, however, was not done. We piled back into our cars and headed to the Jonah Field, a 21 thousand acre natural gas development in the Green River Valley. Begun in the 1990s, the project entails drilling 3,500 wells all over this basin. We were silent as we drove past well pad after well pad. The pipelines, service roads, storage tanks and active drill sites were an affront to the gorgeous landscape all around us. Giant construction trucks rumbled past in unending succession. The Jonah Field was conceived long before the 2015 sage grouse plans and is a case study in the wrong way to undertake energy development. Sage grouse are vulnerable to air, water and ground contaminants and to the noise and reverberations caused by drilling. The birds haven’t been spotted here in 15 years.

Looking at the scarred land of the Jonah Field, we were reminded about why it’s so critical to get conservation policies right. A recent decision by the Department of the Interior to dismantle the 2015 sage grouse protection plans is more than just a little worrisome. The federal government manages almost all of the land where sage grouse and 350 other plant and animal species live. Having federal plans to protect habitat that sweeps across 11 states is just common sense. By abandoning the 2015 plans, the Interior Department is abandoning its duties and encouraging a patchwork solution to a landscape-scale problem. Now it will be incumbent on the states—specifically the governors—to make sure that energy companies don’t file for waivers or exceptions which will weaken sage grouse protections. And it will be incumbent on the states to make sure energy companies mitigate any damage they cause to sage grouse habitat. Our field trip to Wyoming suddenly made all of our plans for advocacy feel much more urgent.

I hadn’t quite expected to be so profoundly moved by the sage grouse spectacle, nor so haunted by the sight of unbridled energy development in the nearby Jonah Field. But something shifted inside me when I was at that lek. The mysteries and magnificence of the natural world remind us of our important role in protecting these treasures for our children and grandchildren. We cannot let oil and gas interests run amok, destroying the habitat for hundreds of sage brush animals. America’s wildlife heritage will only grow and thrive if each of us commits to protecting it.