We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

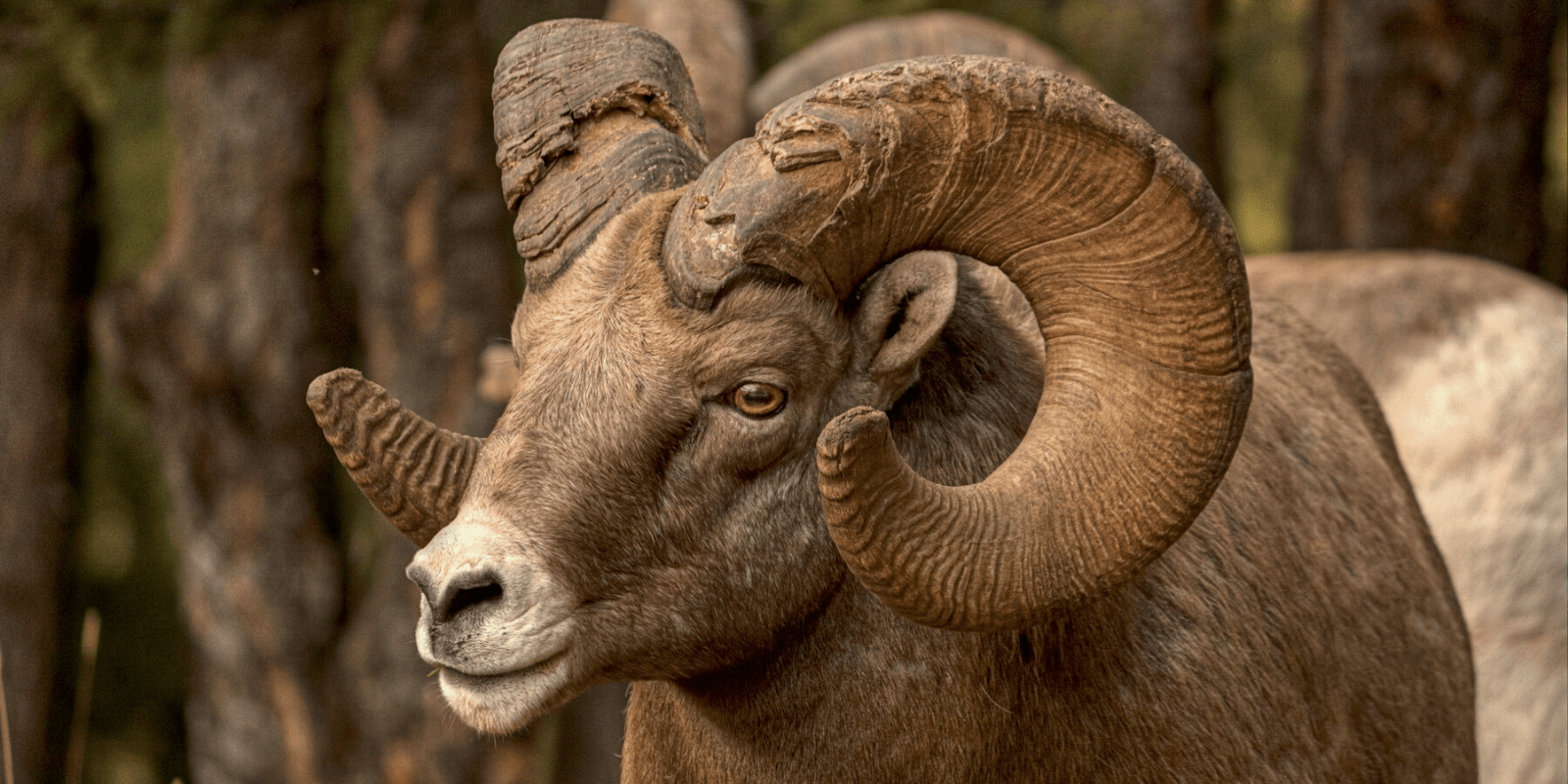

Protecting Bighorn Sheep in the Elk Range of Colorado

Rising high above the towns of Aspen, Carbondale and Marble, Colorado is the Elk Range, some of the highest and most rugged mountains in the United States. There are the two Maroon Bells, Pyramid Peak, Snowmass Mountain and Capitol Peak, all over 14,000 feet. Nestled among these giants are many more peaks over 13,000 feet, named and unnamed. Separating the peaks are high alpine meadows, steep valleys, ice-cold lakes and streams that provide critical habitat for one of the highest priority bighorn sheep herds in Colorado and in addition, mountain goats, elk and other high-elevation species such as yellow-bellied marmot, American pika, white-tailed ptarmigan, brown-capped rosy finch, and nesting peregrine falcons.

And up until this year, when the National Wildlife Federation finalized the retirement of the 33,000 acre Upper Crystal River grazing allotment, 2000 domestic sheep could be found roaming this fragile landscape between the months of July and September.

Unfortunately, domestic sheep carry a number of pathogens that if transmitted to bighorn sheep, can cause the die-off of most or even all of that bighorn herd, something that occurred in the Eastern and Western Snowmass Bighorn herds in the Elk Range in the late 1980s. At that time, the total size of the two herds numbered over 400 individuals, but after likely contact with domestic sheep, the herd experienced an all-age die, the effects of which persist to this day.

The good news is that the eastern herd is slowly recovering, numbering approximately 200 individuals, but the western herd is languishing at approximately 60 animals and continues to decline. Although somewhat speculative, it is possible that this herd was re-infected with another strain of the pathogen causing another die-off event.

The only effective strategy to address this conflict, is to create separation between domestic and wild sheep. The approach taken by The National Wildlife Federation’s Wildlife Conflict Resolution Program is to negotiate a fair-market price with interested ranchers who hold domestic sheep public land grazing allotments in exchange for retiring their right to graze that allotment.

In the case of the Upper Crystal Allotment and the Snowmass Bighorn herd, the Federation staff approached the permit-holder Joe Sperry and negotiated the retirement of his permit. As Joe said, “this was a good business decision for me and a win-win. My sheep had gotten a lot of attention and with the money I received from NWF, I was able to buy another permit for an area farther away from Bighorns which makes the wildlife people happy.” The outcome is that the only domestic sheep allotment in the Elk Range has been removed virtually eliminating the threat of pathogen transmission to wild sheep.

This National Wildlife Federation approach is a completely voluntary strategy and in our view, provides an equitable solution for ranchers who hold permits for high conflict grazing allotments while also meeting wildlife conservation goals by removing livestock from these high priority areas. This market-based approach recognizes the economic value of livestock grazing permits and fairly compensates livestock producers for retiring their leases. After twenty years of success, the National Wildlife Federation has established a new national model for resolving intractable conflicts between livestock and wildlife habitat, retiring to date over 1.5 million acres of public land grazing permits, an area the size of Delaware.

Help support our work for Rocky Mountain wildlife today:

DONATE