We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Protecting “The Great River”

How a Healthy Ohio River is Win for Wildlife & People

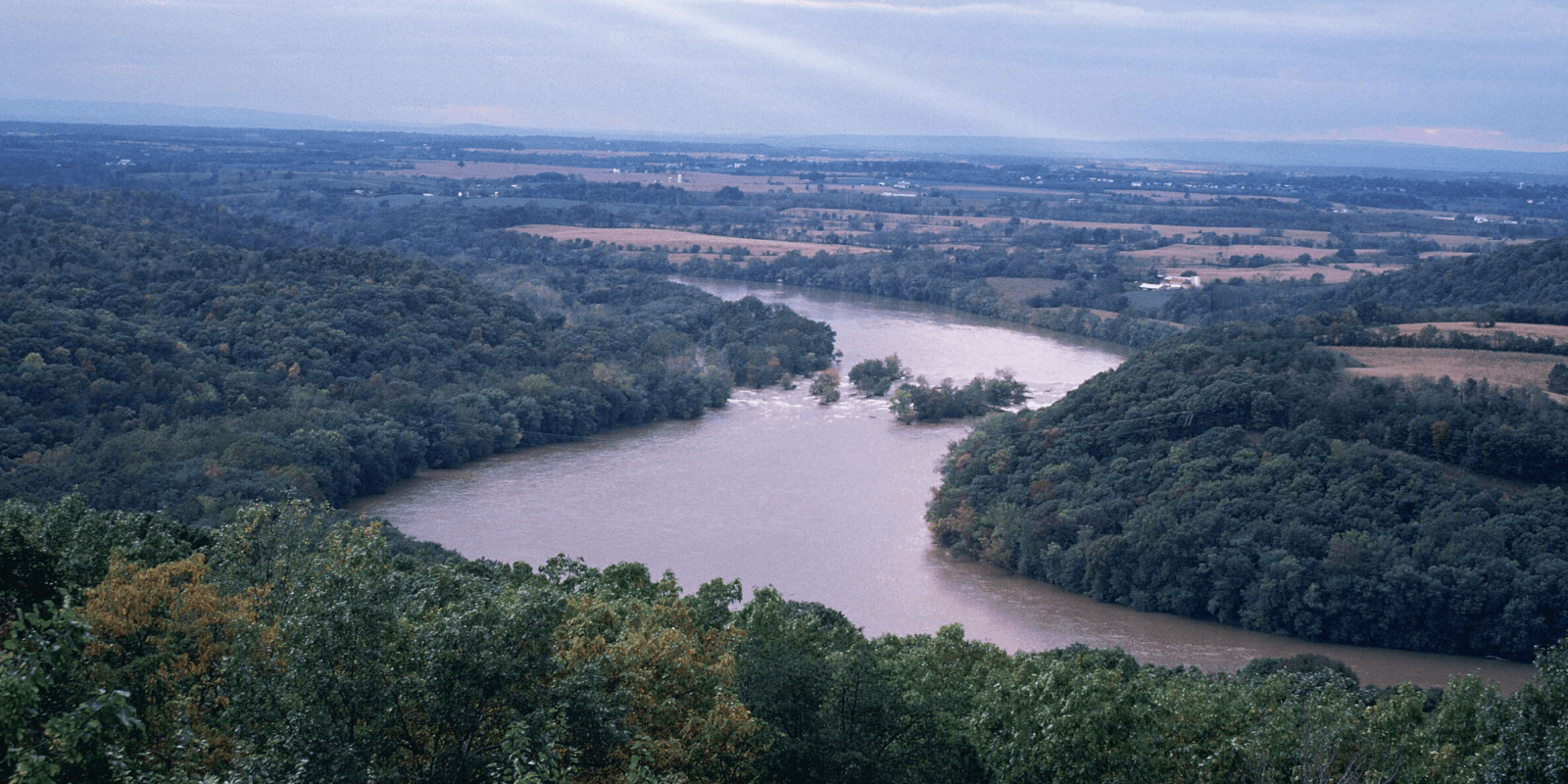

The Ohio River flows over 981 miles of terrain—meandering from Pittsburgh to Illinois where it eventually merges with the mighty Mississippi. Derived from the Iroquois word “O-Y-O” meaning “the great river,” the Ohio’s natural and geographic features create ideal habitat for extensive wildlife such as American mink, fox, migratory birds, and more than one hundred types of fish. From diving kingfishers to underwater mussels to scurrying American minks, the wildlife of the Ohio River watershed depend on us to ensure its waters remain healthy and pollution free. Toxins in the water supply enter the food chain, poisoning birds and mammals, and are one of the main causes of the rapid decline in native mussels—the river’s natural water purifiers.

Vital for Wildlife–and People

Since the river fosters vital economic and community benefits to regional communities, the resulting pollution of the Ohio River is a complex problem. Dating back to the industrial revolution, the Ohio River has presented ideal opportunities for agriculture trade and commerce. To this day, the river serves as an important transportation corridor for shipping and industrial manufacturing. Over 25 million people—almost 10% of the US population—live in the Ohio River Basin, and nearly 5 million people rely on the river for drinking water.

While it provides crucial elements for life, the Ohio is a working river, and hosts 20 locks and dams managed by the Army Corps of Engineers. Each dam that is built alters the natural flow of the river, creating a series of slow moving pools rather than a free flowing river. This results in muddier water which is harmful to benthic (bottom-dwelling) organisms. In addition, the Corps regularly dredges the river further disrupting wildlife and increasing the water’s turbidity, or haziness.

The Ohio River is under constant threat of natural and human impacts. During rainstorms, raw sewage is discharged directly into the river at over 1,350 different locations. As a result, many stretches of the Ohio River near major cities are closed to swimming and other recreational uses of the river. Moreover, urban and agricultural runoff as well as acid mine drainage contribute significant amounts of contaminants to the river.

All of these pollutants contribute to creating an unhealthy ecosystem—many sections of the river do not meet water quality standards for things like bacteria, pathogens, PCBs, lead, mercury, metals, and organics. In addition to a polluted habitat, dams and development negatively impact the wildlife living in and near the river by limiting their movements.

“Approximately 164 species of fish have been found in the Ohio River. However, the dams have drastically altered the habitat for river organisms, as they prevent fish and other organisms from moving up and down the river in their natural cycles. 80 species of mussels once lived in the Ohio River. Currently only 50 species occur and 5 of those are in danger of extinction.”

The Ohio River Foundation, Ohio River Facts.

Committed to the Future

Creating a healthy future for the Ohio River is vital for the communities and wildlife that rely on it. At the National Wildlife Federation, we are committed to ensuring that the river once again becomes a healthy self-sustaining habitat for wildlife and people.

We’ve worked to keep the regional commission responsible for stewardship of the river accountable and have worked to elevate regional concern over pollution policies that would imperil water quality.

While there is still work to be done, the National Wildlife Federation is developing a restoration vision for the River that supports local and state economies while also supporting the wildlife that aren’t able to speak for themselves.

Support our work for wildlife in the Mid-Atlantic region today: