We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Can Western Monarchs Still Rebound?

On a crisp, cloudy morning in late November, biologist Emma Pelton was loving her job even more than usual. Peering through binoculars at the upper branches of a shaggy eucalyptus, Pelton, Western Monarch Lead for the Xerces Society of Invertebrate Conservation, had just tallied 685 monarch butterflies huddled together in a single cluster at Lighthouse Field State Beach in Santa Cruz, California.

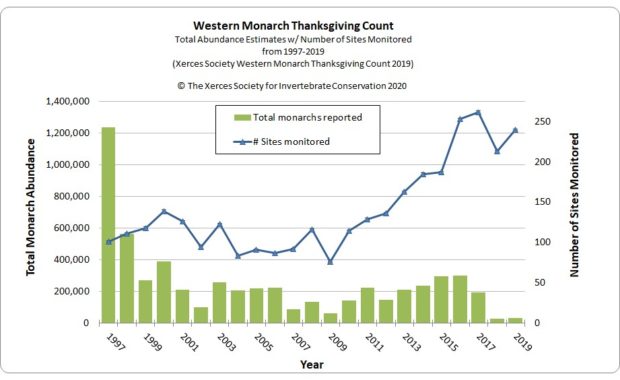

It was day three of 2019’s Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count, an annual three-week population survey organized by Xerces and conducted by volunteers who visit more than 200 sites along hundreds of miles of the California coast. While the 2018 count had yielded the lowest number of butterflies ever recorded—28,429, or fewer than 1 percent of the population’s historic level—2019 seemed to be off to a good start. When Pelton and her companion, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Samantha Marcum, left Lighthouse Field after three hours, they had counted 3,300 butterflies, nearly twice the number recorded in the park the previous year. “This is heartening,” Pelton ventured cautiously. “It looks like our job is going to be a lot more fun than last year.”

Two months later, Pelton is feeling much less hopeful. Announced on January 23rd, final results of the 2019 count showed that participants recorded a total of 29,418 monarchs—virtually the same as the previous year when nearly 30 fewer sites were surveyed. “Obviously, we are disappointed,” says Pelton. “We had hoped the population would have bounced back at least modestly, but unfortunately, it has not.” Particularly worrisome: Both years’ numbers are fewer than the 30,000 threshold below which scientists say that the western population could collapse.

Unlike monarchs that breed east of the Rocky Mountains—the majority of which migrate to Mexico for the winter—most western-breeding butterflies travel to some 400 small forested sites scattered along the California coast. Since the mid-1980s—when an estimated 4.5 million monarchs overwintered on the coast—the western population has been declining, decimated by habitat loss (both overwintering sites and habitats that provide the milkweed monarch caterpillars need and nectar-producing plants required by adults), pesticide use, climate change and other threats. By the mid-2010s, the population had fallen by 97 percent.

Still, 2018’s all-time low was “shocking,” Pelton says. One theory is that the butterflies, which had numbered 192,668 on Thanksgiving 2017, were hit hard by storms in late winter and early spring as they dispersed inland from the coast. No similar weather event occurred in 2018, but although insect populations naturally fluctuate annually, “it gets harder and harder to rebound once the numbers get too low,” Marcum says.

Can the western monarch still bounce back? Pelton remains hopeful. “The silver lining is that the population didn’t shrink any further,” she says. “There are still thousands of monarchs overwintering along the coast, so we can take heart that it’s not too late to act.”

Indeed, if you live west of the Rockies, there are many actions you can take now to help western monarchs, from planting native milkweeds and nectar plants to avoiding pesticides and convincing local officials to sign on to the Mayors’ Monarch Pledge. “It’s relatively easy to create monarch habitat in your own yard or garden,” says National Wildlife Federation Naturalist David Mizejewski. “When we each make an effort to restore habitat right outside our doors, it can add up to big benefits for monarchs.”

More: Find out about five ways to help western monarchs.

Support our work to recover and protect monarchs: