We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

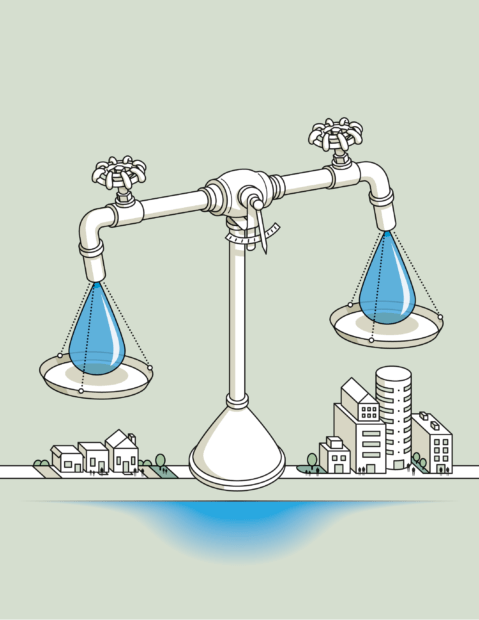

The Fight to Protect Clean Water: Stopping Water Shutoffs

Utilities in Michigan Have Power to Stop Water Shutoffs

The National Wildlife Federation is a long-standing and active partner in the fight for clean water. From protecting vulnerable species from polluted waters to ensuring anglers are able to pass down outdoor traditions to their children, efforts to protect access to clean water have always been at the heart of the conservation ethic. As communities across the country work to stay safe during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s more clear than ever that our fight for clean water must include ensuring that families in Michigan and across the country have access to affordable, clean water.

—

Water is a basic need, yet many Michiganders struggle to afford water for their homes. The problem is not unique to Michigan. Water rates are increasing across the country, and one study estimates that unless things change, more than one-third of Americans will have trouble paying for water. There are many ways to get at this problem. Elected officials in the U.S. Congress can reverse the decades-long disinvestment in local water infrastructure. That would help communities pay for service, while making water affordable. In the short-term, however, local water utilities can extend a helping hand to people by offering lower rates for people who cannot afford their bills. This is not a new idea.

Yet for years in Michigan, water system representatives and municipal officials have assumed that charging for water based on household income is illegal. In the report we co-authored with the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, we prove that these assumptions are false. Water systems in Michigan can charge for water based on household income without running afoul of the law. With the right kind of political will, income-based rates would allow Michigan families to have access to the water they need.

For thousands of households in Detroit, Flint, and elsewhere in Michigan, water systems have disconnected water service mostly due to inability to pay. The coronavirus pandemic highlights this sad fact. During an extraordinary public health emergency when access to water for hygiene is a matter of life and death, thousands of families have no water in their homes. Disappointingly, but not surprisingly, the water shutoff crisis disproportionately impacts communities of color and low-income families who over and over again have been denied access to necessary goods and services.

In nearly every city where significant portions of the population cannot afford the water, the solution has been assistance in the form of subsidies. In Detroit and other communities in the Great Lakes Water Authority service territory, for example, the Water Residential Assistance Program is a fund to which households can apply if they need help paying their bill. However, these subsidy programs are problematic and cannot be the only solution. The subscription rates are too low and the administrative costs can be high.

How to make water affordable

The better solution is to develop an income rate. An income rate is a water rate used to calculate household water bills that reflect the household’s income level and ability to pay. Philadelphia is arguably the first U.S. city to adopt an income rate. There, the water department caps household bills at two percent of monthly income for residents earning less than 50 percent of the federal poverty level; 2.5% for those earning between 51 and 100 percent of the federal poverty level; and three percent for those earning between 101 and 150 percent of the federal poverty level. Based on the 2019 federal poverty guidelines, a family of four that earns $1,610 per month (75% of the monthly guideline figure) would pay $40 per month for water, which is calculated as the monthly income multiplied by 2.5%. For many, that is significantly lower than what it would have cost without the income rate.

Some predict that this can actually lift water system revenues because households that could not afford to pay before will now pay something. Some say that even if it does not in and of itself lift water system revenues, it is the right thing to do. Our report looks exclusively at the legal aspects. Is it lawful for a water system to create and apply an income rate? The answer is, yes. To get there, our report makes three basic points.

Water systems already offer special rates for certain residential households

First, there is a tradition in Michigan of having special rates for seniors, low income households, and other vulnerable populations. The village of Stockbridge and the town of Portage both provide a 10% discount on water usage to all customers 65 and older at their primary residence. Three Rivers provides a 15% discount to such customers. Norton Shores and Harrison both provide a 25% discount to senior citizen customers with a household income of less than $23,431 and $6,000 respectively.

In addition to water service, such discounts are also common in the provision of sewer services, waste disposal, and even fire cost recovery. With so many municipalities applying discounts and special rates, and with so many of those discounts and special rates being justified by hardship, there is nothing new or strange about applying an income rate to a set of household customers to make water more affordable.

Water systems already rely on shared responsibility for water access

Second, income rates comport with the applicable legal standards for ratemaking. Some argue that you cannot charge certain ratepayers more to offset relative losses from other ratepayers. Legally speaking, water systems are allowed to charge some residential customers differently than others so long as there is a good reason for the differentiation and the difference is reasonable.

Water systems could not operate were this not so. For example, the further away from the water distribution system a household is, the more it costs to provide water to it. Yet water systems do not charge households by the foot. When the same rate is applied to numerous households no matter their distance from the distribution point, we overcharge those who live closer and undercharge those who live further. Also, when a water system repairs a water pipe in one neighborhood but not in another, it does not charge the households in the repair neighborhood more.

We are okay with these offsets for various reasons. Practically, it might be too difficult to base water bills on relative distance. For repairs, in the long run all neighborhoods will benefit from one kind of repair or another. There is nothing fundamentally different about income rates. Rather than allow thousands of households to go without a vital necessity, water systems can charge some households less and make up for any revenue loss in other ways.

Making water affordable for the poor does not run afoul of the state constitution

Third, income rates do not violate the Headlee Amendment of the Michigan Constitution. The Headlee Amendment was a response to a taxpayer revolt of sorts. In general, the Headlee Amendment limits the ability of state and local governments to tax their citizens without a vote approving the tax. If a charge is deemed a tax, it must be voted on. If it is deemed a fee, then cities can apply it without a vote.

It should go without saying that the Headlee Amendment does not prohibit income rates. At worst, it would simply require a vote on them.

The report explains, however, that income rates do not even implicate the Headlee Amendment. Drinking water bills have always been treated as fees, not taxes. Nothing changes when a city decides to continue billing everyone but reducing what some will be billed.

Even if income rates did implicate the Headlee Amendment, they should be categorized as a fee, not a tax. According to the oft-cited Michigan Supreme Court case Bolt v. Lansing, for a charge to be a fee and not a tax, it must: primarily serve a regulatory purpose and not simply raise revenue for the city; be proportionate; and be voluntary.

So long as money generated by water rates goes to operating the water system and not to the general fund, the water charge serves a regulatory purpose. So long as households are charged for the water service they receive, the water charge is proportionate. And so long as a household or any other ratepayer can refuse water service for their property, the water charge is voluntary.

For the proposition that income rates are legal, the tailwinds are quite strong. The legal standards that apply to water rates are flexible and accommodating. There is a presumption that a water rate is lawful. There is nothing in the Michigan Constitution that prohibits income rates. And as to water delivery and many other services , we already apply special rates to certain residential households, including those for whom paying the normal rate would be a hardship. All of this and more adds up in our report to one simple conclusion: the assumptions about legal obstacles to income rates are false. If the assumed legal obstacles have been holding back water system administrators and municipal officials from adopting income rates, our report demonstrates that they can do the right thing without having to worry about violating the law.

Building Momentum: What’s Next for Beaver Conservation in Colorado