We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Lead Stopper: The Switch to Copper

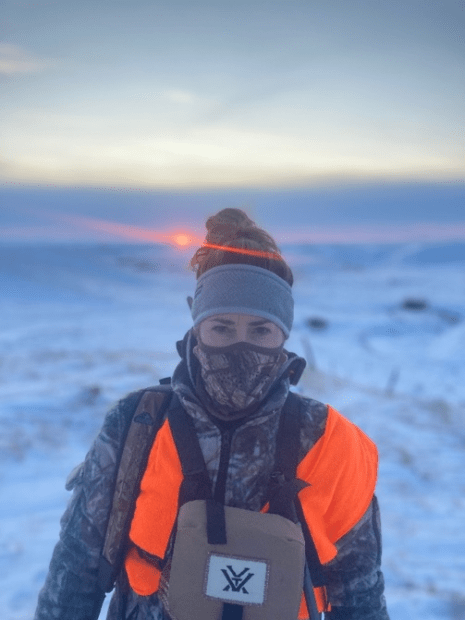

According to the National Park Service, more than 500 scientific studies published worldwide since 1898 have documented that 134 species of wildlife are negatively affected by lead ammunition and fishing tackle. Increasingly, sportsmen—and women, such as the Federation’s Naomi Alhadeff—are adopting safer alternatives to protect wildlife and habitat where they hunt and fish.

There was much to learn when I became interested in hunting, back in 2007, like don’t forget your orange, pretend all guns are loaded, and don’t trespass. What stuck with me —and is highly relevant in my work with National Wildlife Federation—is the ban of lead shot for waterfowl hunting. The lead-shot ban for hunting federally managed bird species went into nationwide effect in 1991. This was banned a long time ago because we knew then the implications of lead. It makes sense.

Lead is a highly toxic metal and a very strong poison that trickles into the water and food chain. However, the ban only forced me to ask other questions. Why just birds? What about big game? Fish? With all that lead being discharged into the environment, plus wild game I consume, what about people?

Lead versus non-lead ammunition has been an issue with hunters for decades, gaining increased scientific and media attention, specifically deer killed with lead bullets. The meat often contains lead fragments, too small for humans to see, and were easily making their way into my diet.

Unfortunately, lead affects the entire ecosystem, but lead bullets affect birds most, especially long-lived birds like our iconic eagles. An estimated 16 million birds are poisoned by lead every year, according to the American Bird Conservancy. Their stomachs are so acidic they actually manage to digest the lead, rather than pass it, making it the number 1 killer of condors.

While the EPA banned lead paint for commercial use in this country in 1978, and the lead-shot ban occurred just over a decade later, sadly lead is still finding its way into birds. So why am I still using lead to hunt big game knowing it ends up in the water, scavengers, and ultimately my freezer? I successfully harvested three deer using traditional lead ammunition over the years, but evidence of the effects of lead was increasingly hard to ignore. A close friend of mine has been using copper bullets for years, so I decided to transition to non-lead for all my hunting pursuits.

In the spring of 2020, I put my name in the hat, hoping to draw a pronghorn tag for the fall. When I discovered I had drawn a tag, I set out to learn how to get my first antelope. I went to friends with more experience and to the internet with questions: How to hunt antelope? What do I wear?

My favorite answer came from my friend and co-worker, National Wildlife Federation’s Director of Wildlife Programs Kit Fisher who quietly said, “get used to shooting at 200 yards.” All the deer I had shot so far had been inside 100 yards. This was the crux of my 2020 hunting experience—practice shooting. Not only was I making the switch to a new bullet material, I needed to prepare to take longer shots. I knew hunting antelope was going to be a different experience, unlike anything I’d tried before. So, I kept practicing. Plus, during the pandemic meant I was having a hard time finding my caliber of non-lead bullets. It took roughly a month to get the boxes I’d ordered – but it was worth the wait.

All the excitement and preparation culminated when “oh-dark-thirty” arrived opening morning. Overdressed but eager, my partner Ryan and I headed to some private land enrolled in Montana’s Block Management Program just a stone’s throw from where his maternal great-grandmother homesteaded. We’d been out only about 90 minutes, glassing for pronghorn when Ryan heard something behind us. Having been leaning on a rock pile, I army crawled back to the top only to see a pronghorn antelope buck with a doe about 250 yards away. I grabbed my gun and realized I wasn’t even loaded, it had been so early into the hunt. All this thought and time put into changing to copper bullets really only matters if the bullets are in the gun. I quickly and quietly loaded three of my fancy new copper bullets. Took aim, and fired.

That night I googled “grilled antelope steak recipes.” Honestly, the tenderloins were without a doubt the best meat I’ve ever had and I know there are no lead fragments in my freezer or the ecosystem. For me, the caliber of the hunt, pun intended, was significantly improved by taking this extra measure. Switching from lead to copper wasn’t without its hiccups.

There were delays in shipping and extra time at the range. In the end, I found I was still able to put dinner on the table. I even filled my deer tag a few weeks later, again using copper ammo. Everyone can make even small changes in this world. Imagine what our ecosystem, in which we live, would look like if we all made minor course corrections.

The National Wildlife Federation promotes the voluntary adoption of lead-free alternatives for hunters and anglers to ensure clean, lead-free landscapes that support healthy wildlife populations. To learn more visit Lead-Free Landscapes or DOWNLOAD OUR FREE BROCHURE ON LEAD-FREE HUNTING AND FISHING.

Learn More