We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

From Backyard Monarch Enthusiast to Citizen/Community Scientist

Misadventures with milkweed

About ten years ago, a neighborhood friend of mine told me with great enthusiasm about her adventures raising monarch butterflies. I was intrigued. I followed her lead and went to a small plant nursery that didn’t use pesticides and bought my first milkweeds. Sure enough, I quickly encountered caterpillars! Unlike my friend, I did not bring the caterpillars inside to raise. Instead, I left them to survive in the confines of my backyard. As the first caterpillars grew and turned into eating machines, it was quickly evident; I needed more milkweed! Soon I was up to 50+ plants. That number would increase every year, as the number of hungry caterpillars increased to approximately 80 at a time!

Around year three, I noticed a disturbing trend among the newly hatched monarchs. Many were unhealthy, deformed, weak, and unable to fly. What was happening!?! I was distressed to see these sick and dying monarchs, and I wanted to know if I had done something that contributed to this unhealthy population. I started doing research, and my distress grew as I read about OE (Ophryocystis elektroscirrha), a debilitating protozoan parasite that infects monarchs. What I learned next stopped me in my tracks: one of the main reasons OE spreads in coastal areas is the predominant use of tropical milkweed, a non-native plant species that doesn’t naturally die back in the winter. Tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) can also interfere with monarch migration and reproduction. What?!? But this plant is so easy to grow and maintain for a non-plant person like me! What are my alternatives? And what can I do with the plants I currently have?

I began to seek out training I could attend, and I did find one located in the Hill Country of Texas, where native milkweed is abundant. I live in Houston, a coastal, tropical climate, where very specific species of native milkweed grow on their own, for instance slim milkweed (Asclepias linearis). I didn’t find the solution I was hoping for, an abundance of native milkweed that I could grow as easily as tropical, or a nursery carrying seedlings of native milkweed that I could purchase. So now what?

I found an organization called Project Monarch Health. Participating meant that I could determine if my monarchs were infected and how badly. And the results the first year I tested showed that 100% of the monarchs in my backyard were positive for OE. I was heartbroken. Most of the monarchs looked normal that year, so I had been hopeful. But now I realized that despite my best intentions, the monarchs that I put out into the environment were sick and spreading OE to other plants, caterpillars, and monarchs. I had read that cutting the tropical milkweed would help prevent the spread of OE, so that winter, I cut all the plants back. Still, the next Spring, the samples that I sent to Project Monarch Health showed almost all the monarchs sampled were positive for OE. The following year, I kept my milkweed plants covered or cut and did not participate. I had still not found an alternative to tropical milkweed. I didn’t want to risk a heavily infected population once again.

Then, during the 2017-2018 winter, something miraculous happened. Houston experienced more than one hard freeze. This freeze caused the tropical milkweed in the greater Houston area to die back and voila, OE rates plunged! But the OE rates started creeping back up the following year when we did not experience a hard freeze in the area. Time will tell what effects, if any, the epic freeze in early 2021 are having on OE rates as data is gathered from the Texas Gulf Coast.

Continued learning as a Master Naturalist

My search for solutions to these OE issues was, in part, what led me to become a Texas Master Naturalist in 2017. I luckily found another monarch enthusiast who is also a plant person. She introduced me to aquatic milkweed (Asclepias perennis) that thrives in our climate. Finally! A native milkweed that I can grow! And it is slowly becoming available at nurseries in the Houston area. I am now replacing the tropical milkweed with aquatic milkweed and I’m happy to report I have no tropical milkweed in my garden.

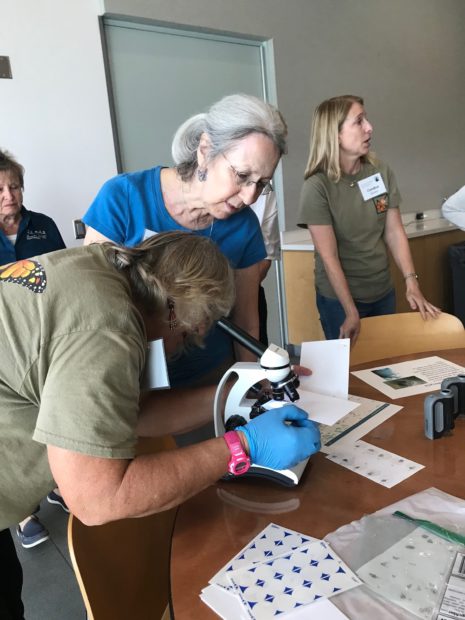

I learned that rearing monarchs in the backyard for fun is not fun for the monarchs. It can have deadly consequences for them. I now only rear a couple of monarchs a year for citizen/community science purposes. To contribute to Project Monarch Health, I catch monarchs with a net, test them for OE (I use my own microscope to get OE results immediately), register the results, and mail the results to the Laboratory. To help slow down the spread of OE, I euthanize those monarchs heavily infected. Currently, I participate in 5 national Monarch Citizen/Community Science projects to help track trends, OE, and the monarchs themselves. As one of the National Wildlife Federation’s Monarch Stewards certification program trainers, I teach participants to test for OE and encourage them to only have native milkweed species in their yards.

So much can be done to help this struggling species! Please consider using native species of milkweed in your garden, researching what species of milkweed are locally adapted to your area. If you have tropical milkweed in your yard, pledge to substitute it with a native species. Also consider becoming a Monarch Steward and volunteering on monarch conservation programs. Texas needs more volunteers testing for OE and to help create a more native, monarch-friendly habitat.

For more information, go to: