We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Closing the Door on Invasive Species

EPA needs to finalize ballast water standard to protect the Great Lakes

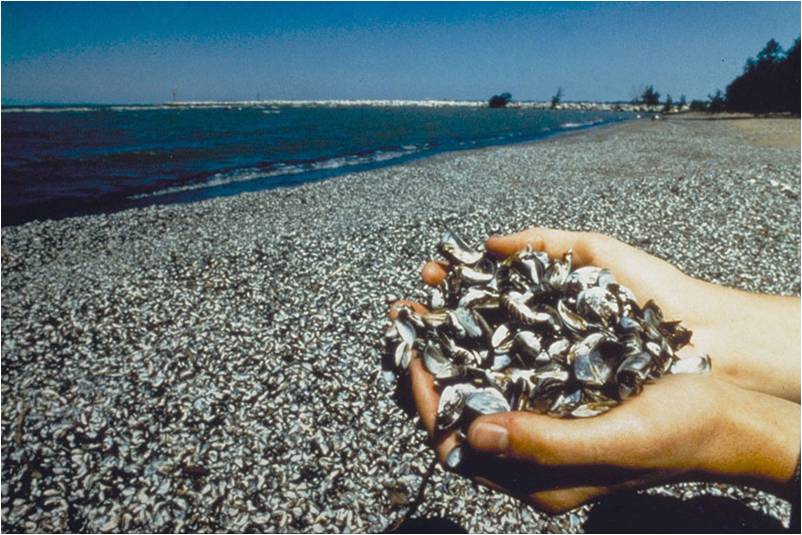

Many years ago, a friend and I landed our boat on the beach at Sterling Park on Lake Erie. Setting up decoys to hunt for waterfowl, we stepped into the chilly mist that encompassed the dark and windy beach. I expected my boots to hit the soft beach sand, so imagine my surprise when instead we heard a loud crunch with each step that we took; it sounded like we were walking across broken glass.

It wasn’t until the sun began to peek over the morning horizon that there was finally enough light to see what was causing the grating sounds. Instead of sand, the beach was coated in nearly a foot-deep of crushed zebra mussel shells. Zebra mussels — an invasive species introduced through ballast water in the 1980s — have wreaked havoc throughout the Great Lakes. But it wasn’t until I was forced to trudge across the blanket of shells that day at Sterling Park that I realized just how prolific they’d become.

If we don’t make changes now to strengthen ballast water standards, it’s only a matter of time before more species with potentially worse consequences further disrupt the native ecosystem of the Great Lakes.

How did we get here?

The steady march of invasive species into the Great Lakes started over a century ago but has ramped up in the last six decades with the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway. This massive human-made waterway connected the Great Lakes and the oceans around the globe for the first time when it opened in 1959.

While the Seaway proved a boom for commercial shipping, it also introduced a host of invasive species via ballast water into the accommodating freshwater Great Lakes. In fact, over 60 percent of all non-native invaders discovered since the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway are attributable to ballast water discharge from ocean-going vessels.

Common in the hulls of cargo ships to provide stability in rough sea conditions, ballast water also allows invasive species to hitch a ride across oceans. Scientists, conservationist groups, and outdoor enthusiasts have long called for strong regulations over how commercial ships operate in public waterways, but the regulations are still lacking — so the invasive issues continues to grow.

Invasive species have proliferated over the years and so have the problems they cause. For example, the poster child of invasive species, the zebra mussel, has myriad negative impacts on the lakes, including depriving other plankton of food, transferring nutrients to the lake bottoms, and contributing to the growth of harmful algal blooms.

To survive, zebra mussels must attach themselves to a hard object like a rock, the hull of a ship or a metal pipe. Factories, power plants, and water treatment systems are constantly dealing with the expense of mussels clogging their intake pipes. And if that weren’t enough, when they die, zebra mussels leave behind shells that wash ashore by the thousands — just like the beach at Sterling Park. These shells not only detract from the natural beauty of the shoreline, but they’re also sharp enough to cut a bare foot.

The invasive species — zebra and quagga mussels, Eurasian milfoil, among others — have entered the Great Lakes in the ballast water discharged from ships. The newcomers devastate local aquatic populations by consuming large quantities of phytoplankton and algae, taking away nutrition from smaller fish. This, in turn, reduces the food available for prized walleye, lake trout, or salmon, reducing opportunities for anglers who enjoy fishing opportunities on the Great Lakes.

In addition to hurting outdoor recreation, invasive species can damage pipes, pumping stations, reservoirs, and other public and private infrastructure, harming local economies. The critters are small, but their impact is large, costing the Great Lakes region more than $200 million each year in damages and control costs.

The problems continue

Oceangoing vessels — or ‘salties’ — can carry large quantities of ballast water — sometimes millions of gallons — and then discharge or exchange it when they reach a port where they unload or load new cargo. If that port is on the Great Lakes, via the St. Lawrence Seaway, then the discharged ballast can include all kinds of unwanted visitors, including the invasive species that are harming local fisheries and water systems.

But oceangoing vessels aren’t the only problem. Studies show that all vessels — including “lakers,” or commercial vessels that don’t leave the Great Lakes — contribute to moving invasive species around the region.

The Great Lakes are a multi-faceted ecosystem, one that includes commercial shipping and other job-creating economic activity. Protecting our precious waters from invasive species, however, is a long-term investment that requires that all ships that operate in the Great Lakes place stronger controls to stop new introductions and spreading invasive species.

Much like invasive carp, the damage by invasive species introduction via ballast water is not just a Great Lake problem, it’s a national problem that needs a national response.

What are the solutions?

In October 2020, the U.S Environmental Protection Agency published a draft ballast water standard intended by Congress to limit the damage caused by invasive species. However, the EPA proposal falls short of providing the strong safeguards needed to aggressively address the problem. One major issue: The EPA proposal gives a free pass to “lakers” or large ships that only operate in the Great Lakes but play a major role in spreading invasive species from one waterway to another. In addition, the EPA failed to utilize best available technology to help set the standard.

The good news is that this draft standard was never finalized before the Biden Administration took over in January of 2021. Over the past two years, EPA has been more or less quiet on this. Last summer however, they did have several listening sessions with industry, conservation organizations, and other stakeholders on the ballast standard.

NWF and other conservation groups provided additional comments for consideration. The biggest update since Oct 2020 when the draft standard was issued is that Canada finalized its long-awaited ballast water standard. Remember, we share the Great Lakes with our friends to the north. While not as protective as we would have liked, in short, the Canadian standard does require that all ships that move through the Great Lakes — salties and lakers — must be regulated and have technology on their ships to prevent the discharge of invasive species.

Having one standard management practice will make it easier for the shipping industry to comply with ballast management, so having Canada on the same page will be important. Moreover, it doesn’t give lakers a pass. The US EPA must at a minimum be consistent with the Canadian ballast standard and require that all vessels be regulated under the Clean Water Act.

Unfortunately, nothing has come from EPA since last summer. So, in an effort to raise the urgency and push EPA to act, NWF recently joined with 160 environmental, wildlife conservation, public health, commercial, and sport fishing organizations, Native American tribes, water agencies, lake management societies, environmental law foundations, local government agencies, and others — including local, state and regional organizations in 38 states — in sending a letter asking President Biden to direct the EPA to establish ballast water standards that comply with the Clean Water Act.

It is long overdue to advance a ballast water standard that regulates all vessels, uses best available technology, is compliant with the Clean Water Act, and protects our Great Lakes and all the nation’s waters from invasive species. We can do this. We have done this before. We have the catalytic converter to control toxic gases emitting from internal combustion engines. And, just look at CAFE standards for the cars we drive. EPA set a standard and the automotive industry had to design cars to be more fuel efficient. This same approach can and must be applied to ballast water management.

Our Great Lakes are too important to our economy, our wildlife, and our quality of life for us not to work together to solve big problems like preventing invasive species from spreading across the Great Lakes via ballast water discharge. We hope the Biden EPA will move on this and finalize a ballast water standard that protects the Great Lakes and all waters across the country.

And maybe in the not-so-distant future, the beach at Sterling Park on Lake Erie will once again be soft sand — no longer razor-sharp zebra mussel shells.

Marc Smith is based in Ann Arbor, Michigan and is the Policy Director for the National Wildlife Federation’s Great Lakes Regional Center. He also is a Commissioner serving on the Great Lakes Commission representing the state of Michigan since 2019.