We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

How Does Wildfire Smoke Affect Wildlife?

Have you noticed the summers getting smokier? If you’ve found yourself coughing more, seeing the sky tinged with an eerie orange, or even just catching the faint scent of burning in the air, you’re not alone. We all know that this smoke isn’t great for our human lungs, but have you ever stopped to wonder how it might impact our wildlife?

Fire has always been a critical component of the Earth’s natural systems. Countless species and entire ecosystems, such as prairies, savannahs, and pine barrens, would not exist without it. Indigenous peoples have long understood this, using fire to enhance natural systems and produce food. However, this restorative relationship between fire and the environment has changed dramatically in recent decades.

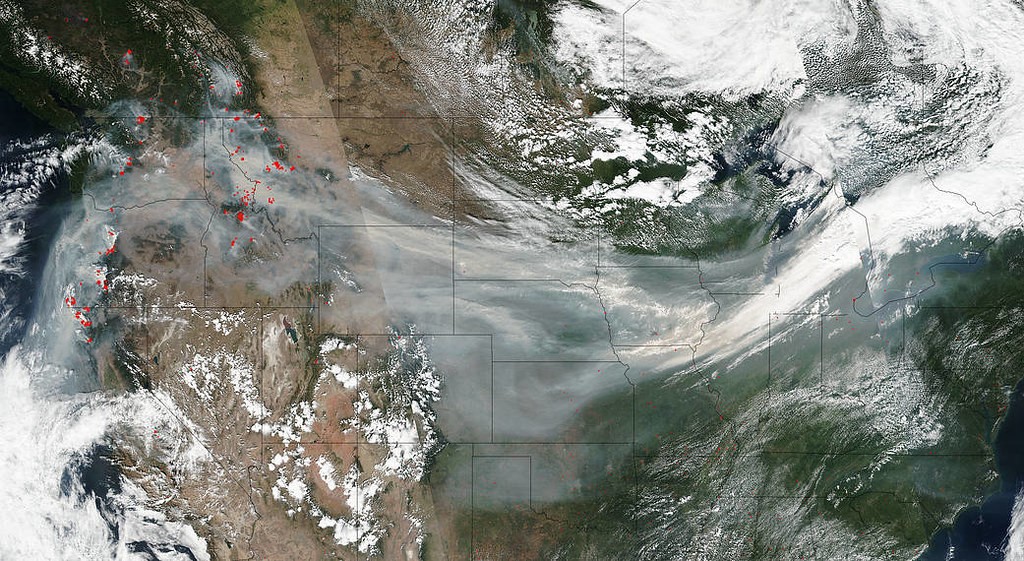

For example, in 2023, Alberta, Canada, was hit by over 650 wildfires, burning an area 150 times larger than the total area burned in the previous five years—over just a few short months. The smoke from these fires traveled thousands of miles, casting a hazy pall over cities and countryside alike. These blazes were not the first, nor the last, of this century’s massive megafires.

These unprecedented large wildfires aren’t just a series of unlucky natural disasters; they’re a symptom of much bigger problems: climate change, and poor land management choices. Our planet’s average global temperature is rising, and that’s leading to more frequent and more intense wildfires. This, coupled with historically mismanaged fire—including the suppression of fire in places where its presence is crucial for ecosystem functioning—has caused a shift from fire as a primarily regenerative power, to an unnaturally destructive force. Some scientists even say we might be entering a new epoch, the ‘Pyrocene’, where these large-scale megafires become a normal, devastating feature of our world.

These unnaturally destructive megafires are now thought to threaten more than 4,000 species globally. But while we’ve got a pretty good handle on how fire itself affects wildlife, the impacts of increasing quantities of wildfire smoke are less understood. What evidence we do have points to potentially devastating impacts on terrestrial and aquatic wildlife alike.

A Hazy Threat

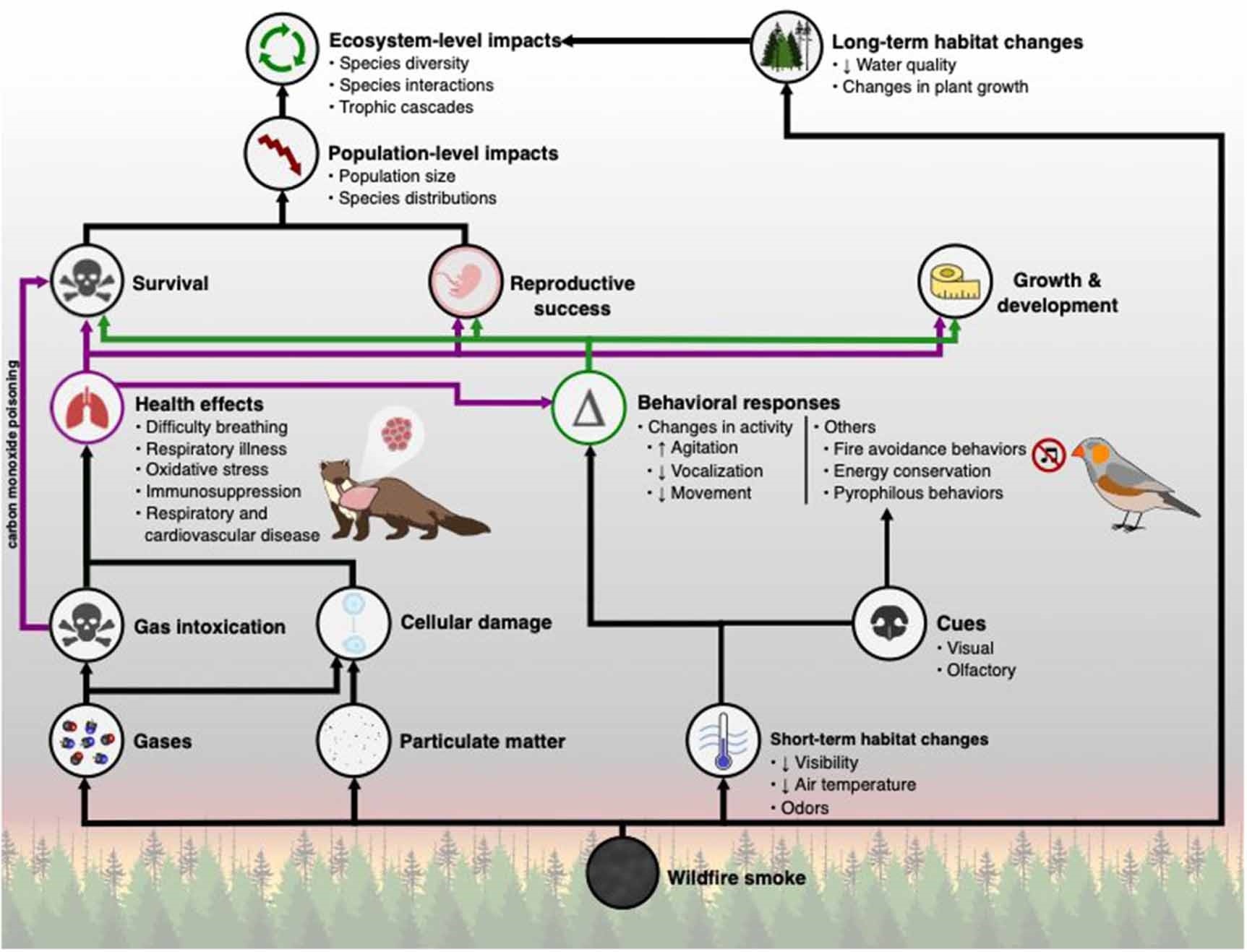

When we talk about wildfire smoke, we’re not just talking about a bit of soot and ash. This smoke is a cocktail of airborne toxins, including gases like carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen cyanide (HCN), as well as coarse and fine particulate matter. These aren’t ingredients you want in your air, whether you’re a human, a hare, or a hawk.

These toxins can damage lung tissue, and lead to low blood oxygen levels or high blood carbon dioxide (CO2) levels. This can cause confusion and stupor, sometimes making animals more vulnerable to predation as they attempt to flee wildfires.

Unfortunately, these lung injuries can last much longer than the fire itself. One study even found that rhesus macaque monkeys exposed to wildfire smoke as newborns had reduced lung capacity and weakened immune responses in adolescence—about a whole year later—compared to those born into good air quality.

Smoke inhalation and the damage it causes can ultimately lead to significant amounts of death whether or not flames are involved. For example, over 60% of snake and lizard specimens collected at the site of one fire in 2020 died from asphyxiation or carbon monoxide poisoning, rather than the flames themselves. Similarly, smoke inhalation injury or gas intoxication, not heat or fire, likely killed nearly 250 elk in the massive 1988 Yellowstone National Park wildfires.

Not all species are at the same risk when it comes to death by fire smoke. You might assume that birds, being able to fly, are at relatively low risk. But it’s well-established that birds are more sensitive to air pollution than other animals, including humans. This is because birds have a unique respiratory system that allows them to exchange most of the air in their lungs with every breath, unlike most mammals, which only exchange about 10% of their lung volume with each breath.

As a result, birds inhale a higher concentration of the toxins present in wildfire smoke, making them particularly susceptible to smoke poisoning. In fact, when scientists attempted to find the cause of a mass avian mortality event that occurred across the western U.S. in 2020, in which 1 million birds died, it was the year’s extensive wildfire smoke—not flames—that emerged as a possible culprit, along with low temperatures and insect food resources.

Smoke Signals

Wildfire smoke doesn’t just affect the health of wildlife; it can also trigger significant changes in their behavior. Wild animals have been evolving alongside fires for over 400 million years, and many species have evolved to respond to the threat it brings by detecting and reacting to smoke on the wind. These species rely on smoke as an early warning system to escape flames, much like us humans do.

Eastern red bats, for example, live in forests and may be subject to multiple forest fires within a lifetime. They have evolved to rouse from their hibernation-like torpor state when exposed to fire smoke, allowing them to escape oncoming flames instead of perishing in them. Similarly, some lizard species from fire-prone ecosystems have evolved to flee quickly once they detect smoke, even in the absence of heat.

But not all movement in response to smoke is about escape; some animals use smoke to move toward fire. Some species are attracted to smoke because it signals newly available resources in burned habitats. For instance, fire-chaser beetles that lie their eggs in smoldering bark can use smoke signals to find breeding habitat miles away.

Many species of birds of prey, especially Swainson’s hawks, are also attracted to smoke plumes. For them, smoke signals an opportunity to prey on insects and small mammals fleeing fire. In fact, raptor activity increases seven-fold during wildfire events in the Midwest, a behavior known as ‘pyric carnivory.’

Interestingly, it seems that at least some small mammals, like the Australian yellow-footed antechinus, seem to use these same smoke signals to escape pyric carnivores. When exposed to smoke, they enter torpor to avoid daytime activity after a fire, and therefore the clutches of fire-hunting raptors.

But keep in mind that not all wildlife populations have evolved to respond to wildfire smoke. This is particularly true for populations that live in areas that rarely burn, such as regions with high moisture like wet gullies, or low fuel loads like rocky outcrops. These populations are considered ‘fire-naive’ and may not have developed early-warning responses to smoke.

However, as climate change expands the footprint of wildfires, these species could find themselves increasingly at risk. Just as rapid range expansions of an invasive species can threaten native wildlife, the growing prevalence of megafires could pose a significant threat to fire-naive species.

Smoke on the Water, Fire in the Sky

Smoke’s reach extends far beyond the immediate vicinity of a wildfire, and its consequences go beyond toxic inhalation. It can also blanket the sky, limiting visibility and cooling the air temperature. These environmental changes, too, can significantly influence the survival of wild animals.

A heavy blanket of smoke can block sunlight from reaching plants, slowing photosynthesis and reducing the amount of food available for herbivores. What’s left is often a landscape of plants covered in toxic particulate that, if consumed, can be harmful to wildlife. Smoke even impacts aquatic habitats. It limits how far light can penetrate underwater, which can influence the number of photosynthetic organisms, like algae, present in water. This can even halt the productivity of coral reefs and other aquatic ecosystems. In addition, aerosols from smoke can be deposited in water, degrading water quality and affecting the ability of fish and other aquatic animals to breathe.

So, what can we do about all this? The unfortunate reality is that these megafires are a direct result of a devastating interaction between climate change and historically uninformed fire management, and their frequency and intensity are likely only going to increase in the future. In fact, top scientists predict that the number of yearly megafires will increase by 50% globally by the end of the century if current trends continue.

That is a sobering outlook, but it’s not one without hope. We can all play a part in reclaiming fire as a natural, ecological process. If we care about wildlife and preventing the impacts from these out-of-hand fires from outpacing their restorative benefits, we need to act—using our voices and our votes—to support policies and initiatives that prioritize climate action and responsible land stewardship. Together, we can push for policies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, protect our forests, and invest in sustainable practices.

Learn how the National Wildlife Federation is tackling climate change here.

Sources

- Álvarez-Ruiz, L., et al. (2021). Fire shapes lizard behavior through olfaction. Behavioral Ecology, 32(4), 1005-1012.

- Hovick, T. J., et al. (2017). Pyric-carnivory: Raptor use of prescribed fires. Ecology and Evolution, 7(22), 9144-9150.

- Jordan, P.R. et al. (2020) Fire-associated reptile mortality in Tembe Elephant Park, Africa. Association for Fire Ecology, 16:3.

- Milberg, P., et al. (2015). A burning desire for smoke? Sampling insects favoured by forest fire in the absence of fire. Journal of Insect Conservation, 19(1), 55-65.

- Sanderfoot, O. V., et al. (2021). A review of the effects of wildfire smoke on the health and behavior of wildlife. Environmental Research Letters, 16(12), 123003.

- Singer, F. J., et al. (1989). Drought, Fires, and Large Mammals. BioScience, 39(10), 716-722.

- Venn-Watson, S. et al. (2013). Assessing the potential health impacts of the 2003 and 2007 firestorms on bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops trucatus) in San Diego Bay. Inhalation Toxicology, 25(9), 481-491