We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

The Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative

Nearly two decades of successful work

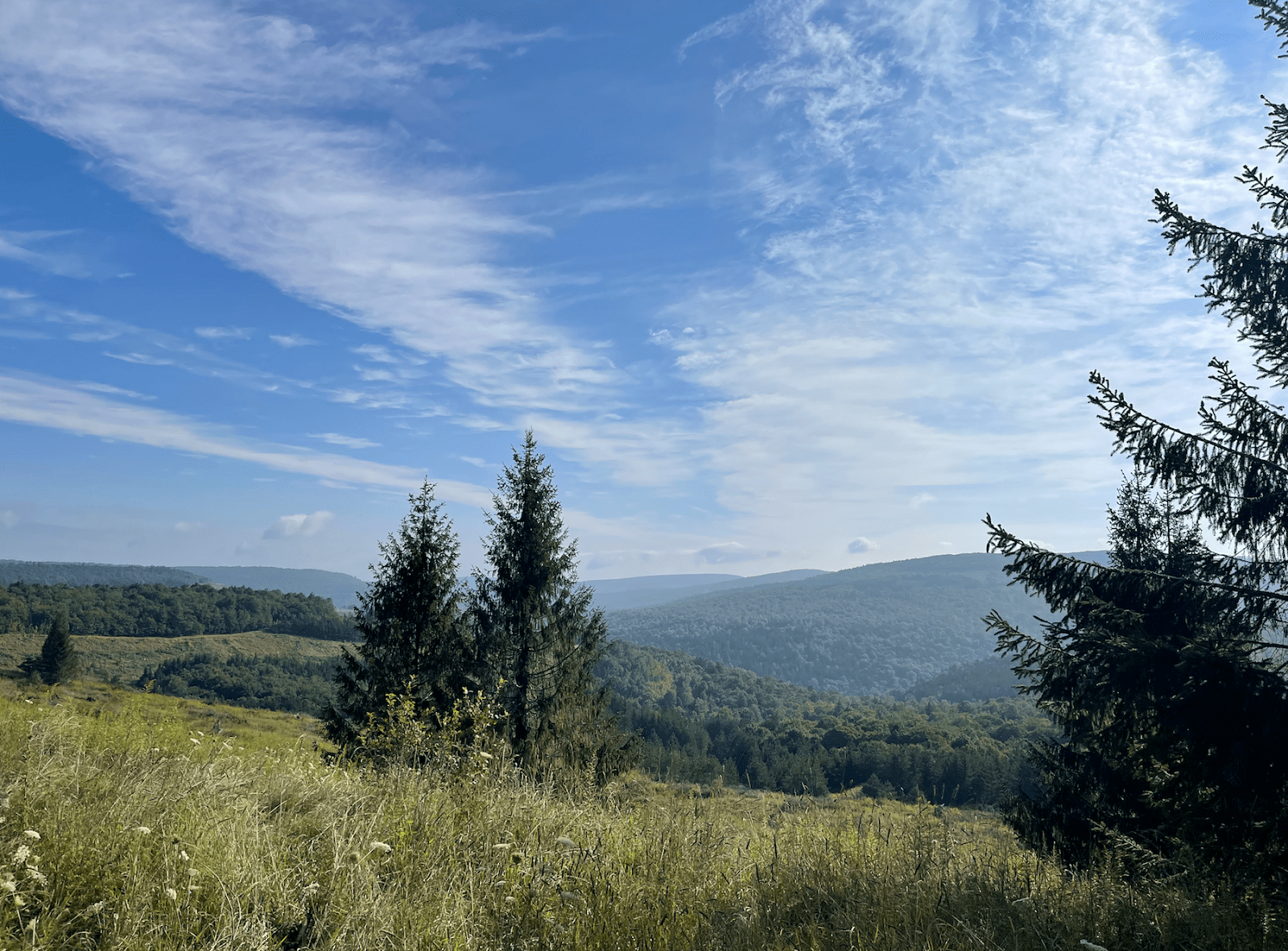

Mower Tract is a sliver of the Monongahela National Forest—40,000 acres out of a total of 900,000—sitting along Cheat Mountain in eastern West Virginia. Its red spruce forest and wetlands are a rich and unique ecosystem; red spruce forests require cool, moist climates to grow and mature fully, and are thus limited in range. Mower Tract is home to northern flying squirrels, snowshoe hare, brook trout, salamanders, frogs, and numerous other wildlife. But it wasn’t always this way.

Decades of clear-cutting and coal mining had previously all-but-eliminated the native red spruce, while reclamation efforts compacted the soil and inhibited native vegetation growth. By the 1980s, what had once been a sprawling landscape totaling 1.4 million acres of red spruce and red spruce-northern hardwood forests was reduced to only 50,000 acres.

Reforesting Mine Sites in Appalachia

The restoration of Mower Tract was possible thanks to the Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative (ARRI), a federal program designed to improve reforestation success on mine sites nationwide. ARRI’s driving mission is to plant more high-value native trees, increase planted trees’ survival and growth rate, and expedite the establishment of forest habitats through natural succession on mine sites.

ARRI works with coalitions of stakeholders, including nonprofits and state agencies, that are dedicated to reforesting abandoned and legacy mine lands. Those involved in the Mower Tract restoration led a recent field trip to the site at this year’s ARRI conference, held in nearby Elkins, West Virginia. Kentucky-based nonprofit tree planting organization Green Forests Work, along with rangers from the U.S. Forest Service, explained how Mower Tract’s original reclamation work involved planting only non-native conifers, and compacting the soil.

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) is federal legislation that governs reclamation of surface and underground coal mine sites permitted before 1977. SMCRA only requires that companies return mined sites to their original contours and prevent future erosion; because of this, mining companies tend to compact soil and replant hardy, resistant conifers, instead of native vegetation.

Reclamation Work for Native Plants at Mower Tract

At the Mower Tract, native species of plants were unable to grow amid the tightly compacted soil and roots. Green Forests Work implemented the Forestry Reclamation Approach—ARRI’s primary approach to reforestation, which prioritizes returning minelands to productive, healthy forests—and first loosened soil, allowing native plants to regrow while providing a suitable habitat for other native tree roots to expand.

In fact, in a seed bank study conducted on the Mower Tract, 45 species of plants were identified in pre-ripped soil. After decompaction, researchers identified over 100 new species of plants and vegetation in the same soil.

The reclamation work takes time—noticeable growth from red spruce plantings doesn’t occur until almost five years after planting, according to Dave Saville, a nursery manager with Appalachian Forest Restoration, another company involved in the Mower Tract reclamation. The company ensures high-quality red spruce seeds are collected, stored, and maintained for use by forestry managers across the region.

The restoration work has benefits beyond wildlife and native plants. Red spruce planting provides an excellent carbon capture technique, as the trees are well-known for storing large amounts of carbon in the soil, preventing carbon return into the atmosphere. Additionally, the process of reforestation supports multiple job opportunities for planters, forest managers, contractors, nurseries, timber production, as well as ancillary jobs in the outdoor recreation economy.

During the field trip, USFS Ranger Jack Tribble showed off one example: the Mower Tract Basin Trail. This 12-mile bike trail is West Virginia’s first mountain bike destination to be recognized by the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA), known for its single-track trails suitable to all skill levels. Eight miles of hiking and biking trails have been developed with over 30 new campsites recently built in the restored area, a significant investment in outdoor recreation infrastructure on abandoned legacy mines.

A short drive down the road from the trail, the dichotomy between forest sites that have seen the impacts of the Forestry Reclamation Approach (FRA) and those that haven’t is noticeable. Downed conifers line the hills along the road, but as the rangers explain, these trees provide habitat for local wildlife while the decomposing wood provides needed nutrients to the soil, increasing its fertility and water-holding capacity.

These conifers could withstand the compacted soil found in reclaimed sites, but their roots never fully matured and choked the growth of other native vegetation. Scattering these non-native trees also provide birds with perches where they can disperse additional native seeds along the route, further expanding native vegetation without additional manpower.

The Future of Forest Restoration Work

The combined efforts of Green Forests Work, USFS, and Appalachian Forest Restoration have ensured that this national treasure will continue to provide ecological, environmental, and economic benefits to the region for decades—and show what ARRI is capable of. The program has never received dedicated federal funding, and yet has seen tremendous success.

Between 2018 and 2022 alone, ARRI planted over a million trees. However, ARRI estimates that there are still a million acres of non-forested, bond-released mined lands that could be reforested in the eastern U.S. This program is nationwide, but operates mainly in Appalachia. Even more revegetation success would be possible if this program received dedicated funding, and expanded nationwide. And even more human and wildlife communities could then benefit from the ecological and economic benefits mineland reclamation brings.

In support of success stories like Mower Tract, and ARRI, the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center, National Wildlife Federation, Appalachian Voices, and Reimagine Appalachia are hosting a series of webinars geared at educating local stakeholders and federal and state lawmakers about ARRI, the science behind the FRA, and the progress made towards revegetation on former mine sites.

We hope that you’ll join us on Tuesday, October 24 from 1-2 p.m. ET to learn more!