We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Diversity in Nature, Diversity in Action

Celebrating Accessibility, Inclusion & the History of Environmental Justice

The start of the new year is marked by many important celebrations such as Martin Luther King Jr. Day in January, Black History Month in February, and Women’s History Month in March. These celebrations honor the vast contributions of historically underrepresented groups across our society. In the spirit of these cultural holidays, we want to highlight some of the many Black and Indigenous leaders who have contributed to the advancement of natural sciences and the larger environmental and conservation movement.

Recognizing Indigenous Peoples as the Original Stewards of Turtle Island and Beyond:

Historically, the U.S. environmental movement has not done its part to bring people together, and in some cases has actively harmed people. In his article in the Scientific American, Eric Michael Johnson explains that many of the European settlers who shaped the 20th-century conservation movement believed that to protect natural spaces, people needed to be kept separate from these spaces. This meant that many of our protected lands, such as national parks, were created through the violent displacement of Indigenous peoples who had stewarded these lands for generations. This has led to long-lasting detrimental outcomes for both people and ecosystems.

For example, the Ahwahneechee used fire as a form of land management in what is now known as the Yosemite Valley to increase forage for deer and prevent dangerous forest fires. A 2010 study published in Ecological Applications found that the removal of the Ahwahneechee from their homeland and the introduction of fire suppression practices by European conservationists such as John Muir has made Yosemite’s forests more prone to destructive fires.

Last year proved that disastrous wildfires continue to pose a significant risk to wildlife and people, particularly Indigenous peoples. NPR and CBC reported that in August 2023 Maui, Hawaii experienced a deadly wildfire, which killed 100 people and caused significant damage to Lahaina, which was once the capital of the Hawaiian kingdom. The fire started when winds from Hurricane Dora knocked over power lines that ignited the dry terrain of Maui’s west coast. Before colonial contact, Lahaina was a diverse wetland ecosystem, but this changed when settler plantation owners diverted water from the wetland to irrigate their crops. In the aftermath of this environmental disaster, Native Hawaiians have lost important cultural sites and face the threat of further displacement due to attempted land grabs from realtors.

Despite considerable and ongoing colonial interference, Indigenous peoples continue to expand on traditional knowledge regarding fire and advocate for its use as an important land management tool. For example, Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson is a Métis woman who works as a Fire Research Scientist for the Canadian Forest Service. She has published research on hazards and Indigenous land stewardship including a book entitled First Nations Wildfire Evacuations: A Guide for Communities and External Agencies. This guide uses first-hand knowledge from evacuees to outline best practices for evacuating Indigenous communities during wildfires. She also produces a podcast called Good Fire to “explore the concept of fire as a tool for ecological health and cultural empowerment by indigenous people around the globe”. As environmentalists, we must recognize, honor, and protect the rights of Indigenous peoples, and make concerted efforts to follow the lead of Indigenous leaders.

Grounding Ourselves in the Movement, Lessons from Black Leaders:

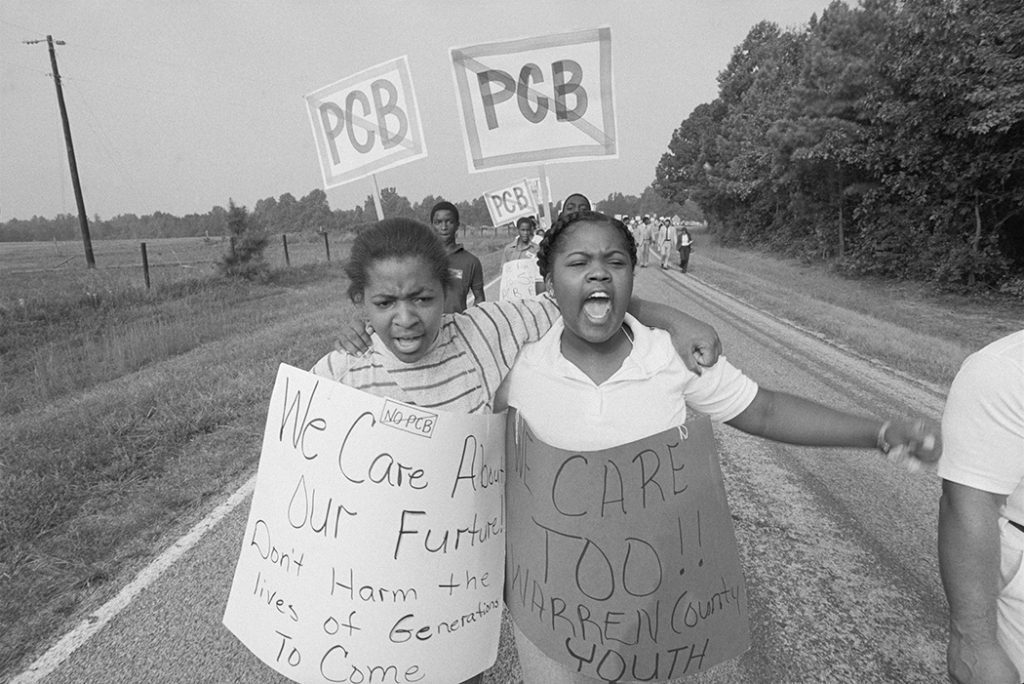

While the struggle for rights over land and equal access to resources has been ongoing for generations, particularly amongst Indigenous peoples, it is widely accepted that the Warren County PCB Landfill Protests marked the beginning of the U.S. environmental justice movement. These protests lasted from 1978-1982 and were a pivotal moment in our nation’s reckoning with environmental racism. The protests began when a coalition of concerned citizens, civil rights leaders, and environmental activists fought state plans to relocate a toxic waste dump site into their majority-Black community. The four-year effort culminated in seven weeks of protests and more than 500 arrests before the state ultimately dumped 7,000 truckloads of contaminated soil in the community.

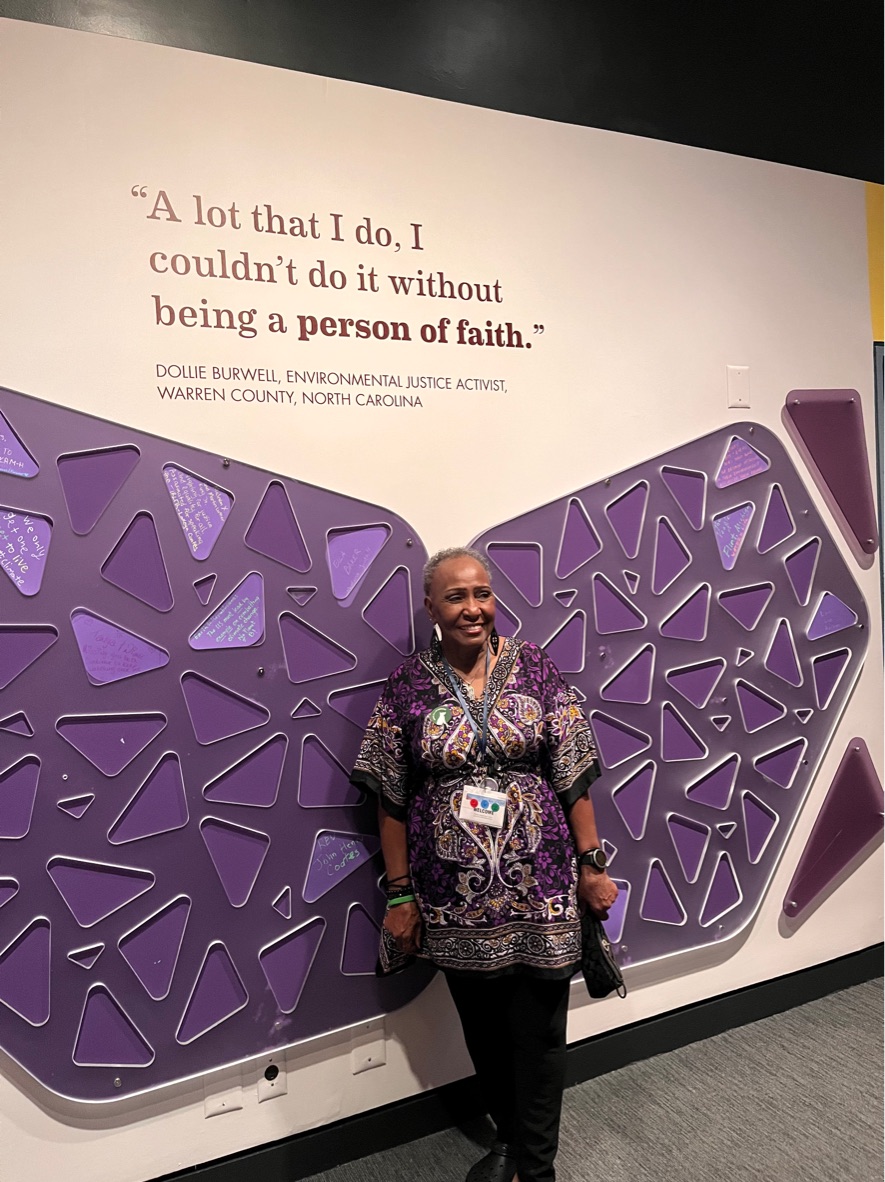

Dollie Burwell, one of the mothers of the environmental justice movement, was an integral member of the Warren County Protests. For six weeks in 1982, Burwell and hundreds of others from predominantly Black North Carolina marched to block trucks from bringing in 60,000 tons of carcinogen-laced soil contaminated with PCBs into her community of Afton, NC. She marched alongside her children and was arrested for her activism. She is pictured (left) at the Smithsonian Anacostia Museum Exhibit ‘To Live and Breathe: Women and Environmental Justice in Washington, D.C.’.

It wasn’t until 2023 that Mrs. Burwell finally received recognition for her early efforts to fight for clean air, water, and a safe community.

Therefore, we must recognize that the fight for access to healthy air, water, and land hasn’t always been met with celebration or understanding, and this is still not applied equally across the globe. Continuing to highlight individuals like Dolly Burwell remains crucial in this movement.

Her activism and the activism of thousands helped illuminate the heartbreaking reality that low-income people, Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) are on the frontlines of pollution and climate change. We owe the Warren County protesters and scholars like Dr. Robert Bullard for paving the way for many of us to engage in environmental protection in our communities.

In his seminal book Dumping in Dixie, Dr. Bullard revealed the gap between “social issues” and “environmental issues”. His book is the first to document and showcase the widespread practice of citing toxic facilities in communities of color. This work built upon the foundations laid by the Warren County protests and other contemporaneous movements. Dr. Bullard shares that his manuscript for Dumping in Dixie was rejected more than a dozen times because the major environmental groups told him they didn’t work on what they characterized as a ‘social issue’, his response was, “Is breathing social?”

Diversity is More than a Buzzword:

These lessons from BIPOC leaders demonstrate the intimate connections between ecological diversity and human diversity. In a healthy, resilient, ecosystem, the diversity of community members, structural processes, and biological legacies are critical for renewal and make ecosystems more stable in the face of change. These same principles apply to the conservation movement. Racially diverse, gender diverse, and culturally diverse groups are better at asking deeper questions and solving complex problems.

We need all hands on deck, and all of us, including wildlife, will benefit. Diversity in science, especially conservation science, is vital as our cultural practices influence the questions we ask, the populations we study, and the procedures we apply. These practices impact how we construct knowledge and conduct science.

“It really boils down to this: that all life is interrelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Martin Luther King Jr, A Letter from Birmingham Jail, 1967

All of us have a stake in our natural resources and a diverse, inclusive profession will allow our goals for wildlife and valuable landscapes to be more relatable and impactful for all people.

Diversity and Inclusion in Action:

Like many longstanding environmental conservation organizations, The National Wildlife Federation was shaped by the white supremacist values that informed the early conservation movement. However, since its foundation 88 years ago, the organization has taken steps to address this history and work towards becoming an anti-racist organization that centers the experiences and knowledge of communities that are most impacted by climate change and other forms of environmental degradation.

In 2020 NWF released its Equity and Justice Strategic Plan, which acknowledged the connection between healthy communities and healthy ecosystems, and affirmed the organization’s commitment to “[ensuring] that all Americans have access to clean air and water, safe communities, easy and equitable access to nature, and protection from the ravages of climate change.” In 2020, NWF also launched a two-year environmental justice assessment to conduct a baseline evaluation of how NWF is currently advancing environmental justice and to provide recommendations on how to accelerate this work in a meaningful way.

The NWF has also adopted a national Tribal and Indigenous Partnerships Enhancement Strategy (TIPES) that will create the foundation and framework for NWF to enhance and expand relationships with Indigenous communities and support Indigenous communities in carrying out their priorities in environmental policy, education, restoration, and more.

This commitment to advancing equity and justice and environmental justice in wildlife protection efforts has also influenced specific NWF programs such as the Mayors’ Monarch Pledge program, which encourages mayors and heads of local and Tribal governments to take action to protect the monarch butterfly, which continues to suffer from significant population declines. In the 2023 program year, communities around the country used this program to celebrate the diverse individuals that comprise their communities and make pollinator conservation more accessible.

Flagstaff, AZ

In Flagstaff, AZ, community leaders collaborated with mural artist Robert Chambers to create a series of murals featuring important pollinator species. The aspiration for the next phase in this project is to include the English common name, scientific name and Indigenous name of each of the pollinators featured.

Lewisville, TX

Lewisville, TX, hosted their 6th annual Mariposas Butterfly Festival in April of last year, which was attended by almost 400 community members. Visitors were able to connect with vendors on statewide conservation initiatives and participate in a wide variety of activities that were suitable for different ages and skill levels. This event was also bilingual, meaning that all information and content was provided in both English and Spanish.

Boise, ID

Finally, Boise, ID, created the Open Arms Dance Project, which featured a monarch migration-themed dance followed by a presentation on the monarch’s cultural significance, migration, and biology. The cast included dancers of diverse bodies, ages, and abilities who performed at public venues and cultural events such as Día de los Muertos celebrations.

This is not an exhaustive list of the ways that National Wildlife Federation programs and partners have sought to make sustainability more inclusive. The organization still has much to learn and is committed to becoming a 21st-century organization that centers on the knowledge and experiences of the diverse communities that make up our nation.

Get Involved!

If you want to support wildlife in your community, consider joining the Community Wildlife Habitat program and a growing network of communities dedicated to becoming healthier, sustainable, and more wildlife-friendly. Check out Garden for Wildlife for more resources on how to create wildlife habitats at home. For more information on monarch conservation and to get involved locally, please visit our Mayors’ Monarch Pledge site and encourage your mayor to protect monarchs.

Tell your mayor or local leader to take the Mayors’ Monarch Pledge before March 31st and access dozens of resources that will help expand quality habitat for monarchs and support diverse community engagement.