We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

C2P2 Connects College Students & Locals on River Health

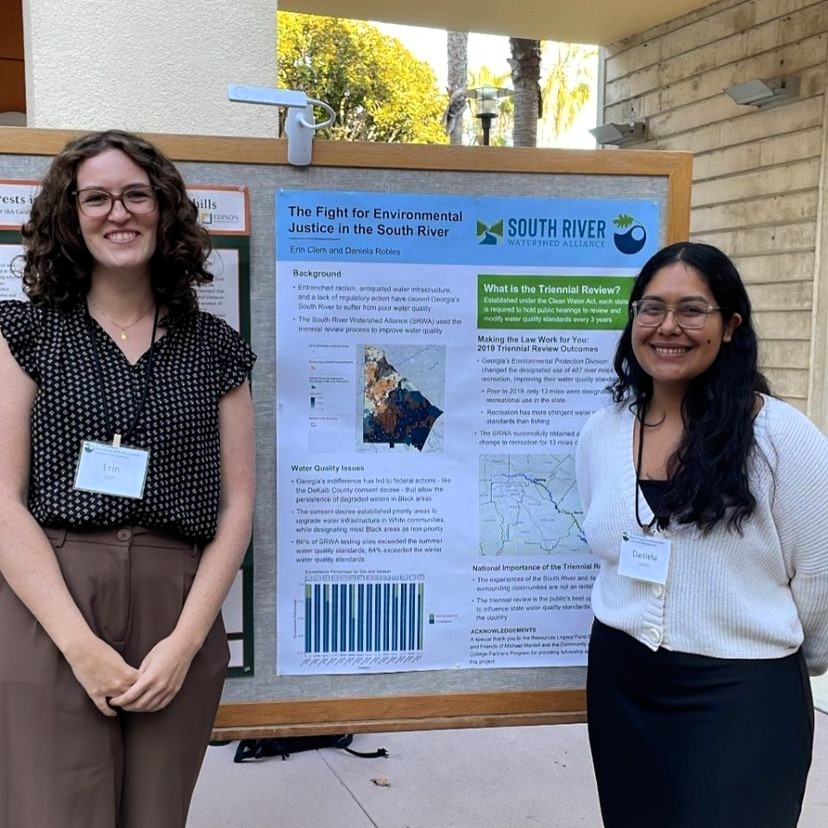

When Daniela Robles—a University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) senior and first-generation student in USCB’s Promise Scholars Program—connected with College and Community Partners Program (C2P2) through an internship in the summer of 2023, she connected with the organization’s commitment to centering community voices within broader movements for environmental justice.

Robles grew up on a ranch in California and always felt a deep reverence for and stewardship of the land. She notes that people’s visions for a sustainable world are integral to crafting justice-informed solutions to environmental problems. “I believe that C2P2 stands for really meaningful work—not only toward environmental justice—but also with the people involved. You can’t have one without the other. C2P2 has a really big human component to it,” Robles explains.

Pairing Experiential Learning with Community Improvement

C2P2, a founding member of the Climate Equity Collaborative, forms trusting and collaborative relationships with underserved communities—nationally and internationally. Their mission is to harness college and university resources to provide the technical assistance needed to address community members’ self-identified solutions to environmental, economic, and quality of life issues. For nearly eight years, C2P2 organizers—including students, educators, policymakers, and non-governmental leaders—have worked with populations in 20 states and completed over 150 projects informed by community members at the forefront of social change.

UCSB graduate student and Bren Environmental Program Leadership recipient Erin Clem identifies immense value in C2P2’s people-driven mission. Clem asserts that equity and justice are crucial components to climate and environmental solutions. Governments, non-profit organizations, and corporate partners must include marginalized communities in decision making. “We can’t achieve our environmental goals without having justice at the forefront of our emissions reductions strategies and climate goals. We don’t want to leave anyone behind or cause any negative impacts on already disadvantaged communities.”

Through UCSB’s Bren Environmental Leadership Program, Clem and Robles started working together as a graduate-undergraduate student team in Summer 2023. Then, they began collaborating with C2P2 Executive Director Michael Burns and the South River Watershed Alliance, a grassroots alliance based in Georgia’s DeKalb County and led by residents along the South River.

The team completed activities including mapmaking, conversations with community organizers in Georgia, and in-depth site visits to observe the community conditions surrounding the South River. Robles and Clem developed nuanced understandings of the web of historical, governance, social, and ecological issues that underpin the poor water quality within the watershed.

The Clean Water Act and Georgia’s South River

Under the Clean Water Act, state policymakers assign individual rivers to different usage tiers, including recreation, fishing, and scenic. “The entirety of the South River was designated for fishing, so it had the least rigorous protections. The South River Watershed Alliance has been trying to use the Triennial Review to increase the designated use to the next standard up, which is recreation, so they have more protections from bacteria and pollutants. Specifically, E. coli coming into the river from sewage runoff,” explains Clem.

The Triennial Review is a federal policy mechanism under the Clean Water Act that mandates states to reevaluate and revise water quality standards at least once every three years and hold public hearings for community input. Clem and Robles witnessed the Triennial Review’s relevancy to the South River when the state designated thirteen miles of the waterway as a recreation site after intensive community organizing. “The next steps the South River Watershed are trying to push the rest of the river to designated recreational sites,” recognizes Clem.

Building Bridges and Listening to Community Members

Beyond developing knowledge around federal and state avenues for regulation, Robles and Clem also interacted with community members and landscapes across DeKalb County firsthand. Through guided tours with South River Watershed Alliance Director Jackie Eccles, the students witnessed the stark realities of racial and economic segregation along the river.

“On one of our first stops, we stopped at the headwaters of the river, which was located right next to a public housing facility. The water was classified as a Class 1 hazardous waste site, which is the highest classification in the state. But we could see that there were very [few] signs and very little fencing up that could protect people from going in or near the water. That just shows the lack of responsibility for the environmental pollutants in Black and poor communities. The waters were very unnaturally blue. They looked like Gatorade,” says Clem.

Robles and Clem detected community members’ hesitancy—and even fear—around the river waters. Due to long legacies of contamination, sewage, and state neglect, residents remained wary of sections of the water even after they had been designated for recreational purposes. As a result, residents along the South River in predominantly low-income and communities of color lack access to green spaces and recreational outlets.

“We actually got to go out to Atlanta and see the river, kayak on the river, and meet people who lived in the surrounding areas. The night we landed, we were getting dinner and talking to the waitress. We said we were going to go to the South River, kayak on it, and check out the problems. And she was like, ‘Oh no, that’s gross, don’t do that because it’s not a safe place to be.’ And you could just see that there’s a big separation from people in the community and recreational activities around the river,” Clem highlights.

Data and Analysis Reinforce Community Perspective

Robles and Clem’s statistical analysis and mapping tools revealed a pattern parallel to their personal observations during their South River headwaters visit. The students produced a map illustrating the uneven distribution of E. coli bacteria across DeKalb County, with higher bacterial concentrations found in predominantly Black neighborhoods.

Robles uplifts the significance of data and geographical analysis as not only evidence-based tools, but critical communications instruments that allow people to truly visualize the weight of environmental crisis. The students translated complex data into cohesive and accessible maps.

“Map-making and spatial analysis are very important communications tools because they demonstrate the disproportionate levels of impact occurring throughout the state and communities. This also demonstrates which parts of the river need more change and updating the standards,” noted Robles.

Next Steps and Future Environmental Justice Careers

Following their intensive learning experiences and research alongside C2P2 and the South River Watershed Alliance last summer, Robles and Clem will attend the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice conference in D.C. this spring. They are keen to circulate data and knowledge on the Triennial Review as a vehicle for environmental justice and improved water quality across all states. The conference will serve as a space not to merely summarize data about the South River, but for the UCSB students to paint a picture of how community action and historical awareness can culminate in a robust environmental justice “win” for a community facing a water quality crisis.

Both Clem and Robles emphasize that their times spent with C2P2 and the South River Watershed Alliance have undoubtedly influenced their future career paths. Says Robles, “I want to enter a career field where I make a change through conservation restoration work and government agencies and be able to implement a change within these organizations. I want to bring light to communities that have been put to the side and have not been able to communicate their issues with environment injustice and racism.”