We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

The National Wildlife Refuge System: Protecting A Conservation Success Story

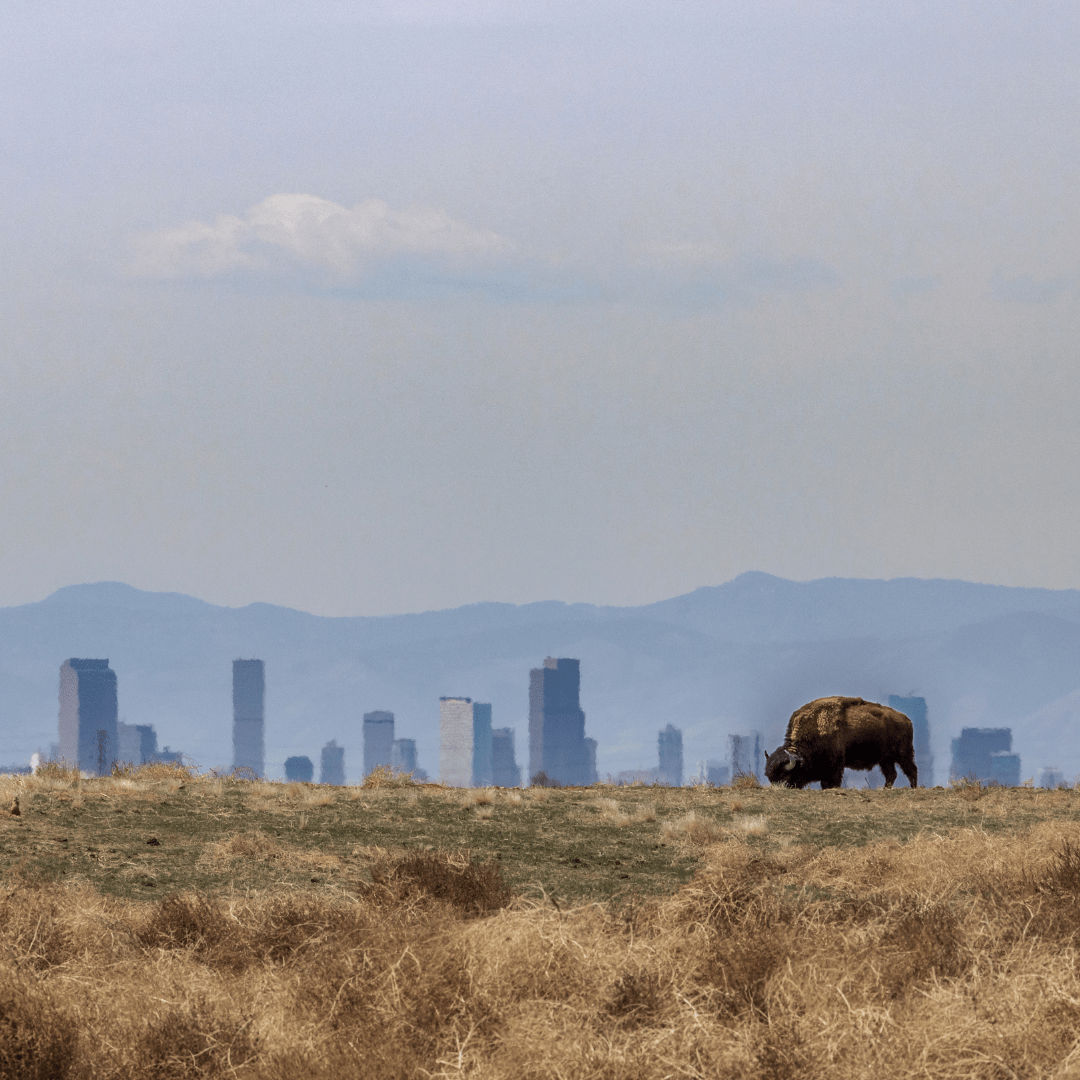

When it comes to protecting wildlife and the outdoor experiences Americans cherish, few conservation efforts have been more successful than the National Wildlife Refuge System. Spanning more than 850 million acres of lands and waters, refuges provide safe havens for thousands of species, including many that are threatened or endangered, while safeguarding wetlands, rivers, and aquifers that help filter pollution and supply clean drinking water to surrounding communities.

These protected landscapes also offer millions of Americans opportunities to hike, paddle, hunt, fish, watch wildlife, and connect with nature—supporting local economies and outdoor traditions.

In December, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service initiated a review of the refuge system to consider, among other things, its alignment with the overall mission of the service and to identify refuges “established for a purpose that no longer aligns with the mission.”

The review, which must be completed in only 60 days, is occurring against the backdrop of recent efforts to sell off public lands, raising questions about whether the review could be used to shrink refuge boundaries, eliminate protections, or pave the way for land transfers. As the process unfolds, it is critical to examine the Refuge System’s history, the legal authority for the Service to add or remove lands, and the potential consequences of the ongoing review.

History of the Refuge System

The first national refuge, at Pelican Island, Florida, was established by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1903 to protect native birds. By 1909, Roosevelt had issued 51 Executive Orders establishing wildlife reservations in 17 states and three territories. Responding to public concern about declining wildlife populations, Congress enacted legislation establishing the Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge (1905), National Bison Range (1908), and National Elk Refuge (1912).

To address the continued decline of migratory birds, Congress enacted the Migratory Bird Conservation Act in 1929 and the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund in 1934 to provide authority and funding for the Secretary of the Interior to create additional refuges.

In 1956, Congress enacted a national fish and wildlife policy through the Fish and Wildlife Act, which authorized the Secretary to acquire lands for fish and wildlife management and conservation through purchase, exchange, or donation but did not provide funding for that purpose.

In 1966, the existing refuges and other wildlife conservation areas (e.g., wildlife ranges, wildlife management areas, and game preserves) administered by the Service were consolidated through the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act (“Refuge Administration Act”).

There are currently 573 national wildlife refuges and five Marine National Monuments in 50 states and five U.S. territories, encompassing 95 million land acres, 760 million marine acres, and over 1,000 miles of wild and scenic rivers.

The mission of the Refuge System is “to administer a national network of lands and waters for the conservation, management, and where appropriate, restoration of the fish, wildlife, and plant resources and their habitats within the United States for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.” In refuge planning and management, the Service must prioritize wildlife-dependent recreational uses if they are compatible with the purpose for which the refuge was established.

How are lands added to the Refuge System?

According to a January 2025 report from the Congressional Research Service, of the 573 refuges, more than 500 were established through administrative actions (presidential proclamations, executive orders, and secretarial orders) and the remaining refuges were established or modified by Congress through legislation.

Some refuge lands are reserved from the public domain, which means they are public lands obtained by the United States through treaty, purchase, or annexation that have never left federal ownership. As of September 30, 2025, there were nearly 82 million acres of lands within the Refuge System reserved from the public domain.

Other lands are acquired through purchase, exchange, or donation. Congress has enacted multiple laws providing authority and funding for the Secretary of the Interior to acquire lands for the Refuge System, including the Migratory Bird Conservation Act of 1929, Duck Stamp Act, Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1934, Fish and Wildlife Act of 1956, Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965, National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966, and Endangered Species Act of 1973. As of September 30, 2025, there were over 5.6 million acres within the Refuge System that had been purchased by the Service, at a combined cost of over $3.1 million.

How can lands be disposed of within the National Refuge System?

In general, an act of Congress is required to dispose of lands within the Refuge System. The Refuge System Administration Act provides that, with certain limited exceptions, areas (1) designated by law, Executive order, or secretarial order; or (2) included by public land withdrawal, donation, purchase, exchange, or cooperative agreement shall remain within the Refuge System unless Congress enacts legislation directing otherwise.

An additional prohibition on disposal for lands reserved from the public domain is found in the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), which prohibits the Secretary from modifying or revoking any withdrawal that added lands to the Refuge System.

For other lands, the Refuge System Administration Act allows disposal only: (1) through an authorized land exchange, if the lands to be divested are “suitable for disposition” and the exchange is for property of approximately equal value; (2) if the area was added to the Refuge System through a cooperative agreement with a state or local government, and the agreement provides for disposal; or (3) if the Secretary determines, with the approval of the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission, that the land is no longer needed to serve the Refuge System purposes, and the government recovers its acquisition cost or the fair market value.

In exercising this limited disposal authority, the Service must consider the mission of the Refuge System and the purposes of individual refuge units.

What is the likely outcome of the Service’s review of the Refuge System?

The December order directs Service staff to evaluate, among other things: current resources; ways to improve asset and infrastructure management; capacity of refuge staff to build and maintain partnerships with local communities, States, and Tribes; and opportunities to achieve efficiencies in oversight of the Refuge System. If the review results in concrete recommendations to improve management and outreach while using scarce agency resources more efficiently, it could lead to improved conservation outcomes at refuges.

Another aspect of the review—the directive for staff to identify refuges that were established for a purpose that no longer aligns with the mission—has raised concerns that the Service will target certain refuges, or other lands within the Refuge System, for elimination or reduction in size.

Although it is possible that the Secretary and Migratory Bird Conservation Commission could act on the findings by seeking to dispose of refuge lands found to be out of alignment with current Refuge System purposes, the large-scale removal or sale of refuge lands is unlikely given the limitations on the Service’s disposal authority. However, the Service could seek opportunities to use its land exchange authority to change the footprint of refuges.

The Service may only enter into a land exchange if the acreage that will be removed from the refuge is suitable for disposition. As explained in the Service Manual, the burden is on the refuge manager to document that the exchange: (1) furthers the purposes for which the refuge was established; (2) fulfills the conservation mission of the Refuge System; and (3) provides a net conservation benefit to the refuge.

Therefore, if the Service’s ongoing review identifies lands that will be considered for disposal through exchange, the Service must consider the relative conservation value of the areas and should only proceed with an exchange if the land to be obtained would better serve the purpose of the refuge unit.

In directing the Secretary to “plan and direct the continued growth of the System” and to maintain its biological integrity, diversity, and environmental health “for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans,” and limiting the authority to remove refuge lands, Congress sent a clear message that the Service should seek to expand the Refuge System to increase conservation benefits and opportunities for outdoor recreation. The current review and implementation of any resulting recommendations should be designed to further those goals.