We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Cheatgrass Threatens Wildlife, Western Lands, and Rural Communities

Invading Americas grasslands

Although it has never been cast as the villain in any of the great Westerns produced in Hollywood, Bromus tectorum — commonly known as cheatgrass — is one of the biggest threats currently facing the wild West.

An invasive annual grass that has rapidly spread across 100 million acres of grassland and sagebrush areas, cheatgrass degrades wildlife habitat, diminishes crop production and cattle forage, accelerates wildfires, and reduces the ability of grasslands to effectively sequester carbon.

Cheatgrass provides almost no value as forage or cover for wildlife, but it chokes out valuable native plants that do. Sage grouse, pronghorn, deer, pygmy rabbits, and elk are just a few of the wildlife species that have been negatively impacted by the invasion of cheatgrass.

Fueling a vicious fire cycle

Corey Ransom, professor of weed science at Utah State University, says cheatgrass not only takes over huge swaths of land, it changes the ecology of the area as well. “It actively grows in the winter so it can take full advantage of moisture in the spring — robbing emerging native grasses of water. I liken those native grasses to being the youngest in the family of 7. If you come to the table late, you’re not going to get much food to survive on.”

Ransom says cheatgrass has a short lifespan which means it dries out by mid-July and becomes a super-fuel for wildfires. “We used to see a fire cycle of every 25-30 years in our grassland areas. Now, in areas that have been overtaken by cheatgrass, that fire cycle is down to every 3-5 years,” says Ransom.

What’s even more concerning is that while those fires destroy native grasses and shrubs, cheatgrass seeds survive and remain viable for many years, encouraging an endless cycle of cheatgrass fueling fires which fuel more cheatgrass growth. In fact, according to one study, three years after a fire, cheatgrass can grow back at an astonishingly dense rate of 10,000 plants per square meter.

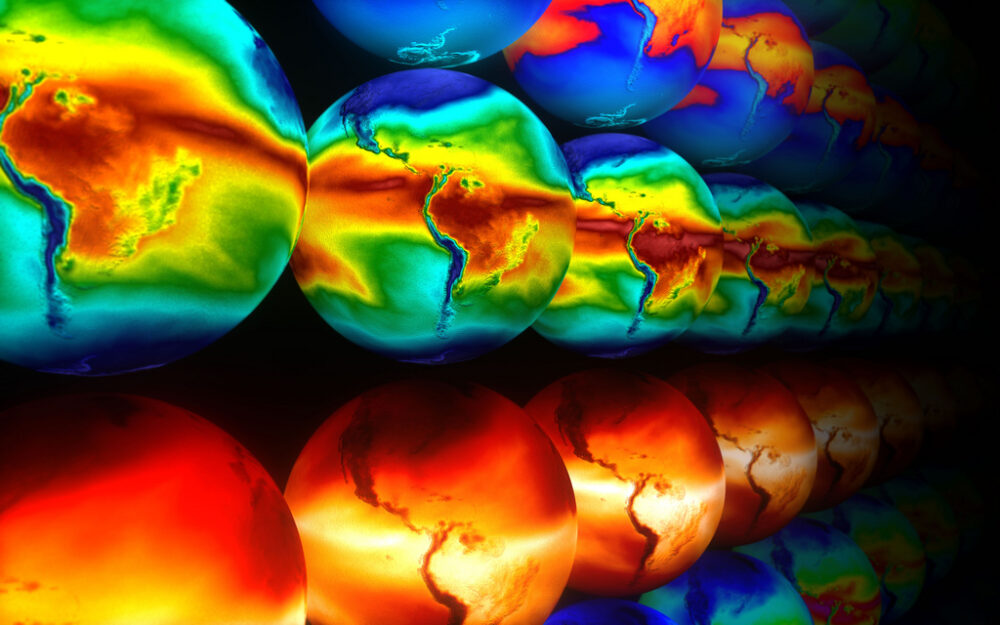

Reducing carbon sequestration

In addition to contributing to more frequent fires, cheatgrass hampers the ability for these large grassland and sagebrush areas to store carbon. Healthy, intact native grasslands have been found to be very good at sequestering carbon — in both the grasses that emerge from the soil and the extensive, fibrous root system below. In fact, according to a study by UC Davis, grasslands might even be more reliable carbon sinks than forests. Cheatgrass, on the other hand, has very little biomass and in areas where cheatgrass has overtaken native grasses, carbon sequestration has been drastically reduced.

According to studies of the Great Basin in Nevada, conversion to cheatgrass reduced above-ground carbon sequestration by 90% and below-ground sequestration by 50%. Considering that 10 million acres in the Great Basin have been degraded by cheatgrass — that’s a lot of lost potential for carbon sequestration!

The good news is that there are some promising projects underway to eradicate cheatgrass and restore the native grasses and sagebrush. Cheatgrass can be removed manually, with prescribed burns, and with the use of herbicide treatments. Using a combination of these methods appears to be the most effective — and the highest rates of success have happened where cheatgrass is just beginning to overtake the land. “There’s lots of research being done and we keep making progress,” says Ransom.

Two years after a wildfire burned more than 35,000 acres in eastern Oregon, the Bureau of Land Management continues efforts to rehabilitate the landscape, by using drills to plant native sagebrush seeds, among others, in eastern Oregon. Credit: Jason Horstman/BLM

The need to Build Back Better

Removing cheatgrass and restoring natural grasses and sagebrush will require serious investments. Estimates run from $40 to $100 an acre. Fortunately, Congress is poised to make historic investments in our grasslands, forests, and sagebrush steppe in the Build Back Better Act. In the long run, removing cheatgrass and restoring natural grasses bring many financial benefits that more than make up for the costs.

Healthy sagebrush and grasslands benefit threatened wildlife species, fight drought, reduce the risk of fire, and sequester more carbon. Healthy sagebrush and grasslands also make nearby communities more resilient to climate impacts and can bolster the outdoor recreation economy by providing more access for hunting, fishing, and other recreation. By some estimates, for every dollar spent on restoration, $15 is generated in economic activity.

But we need to act quickly. Investing in the restoration of our sagebrush and grassland areas cannot wait. It’s imperative that Congress swiftly passes the Build Back Better Act and ensures adequate funding so the Department of Interior can launch shovel-ready projects to remove cheatgrass. Our wildlife and rural communities in the West are depending on it.