We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Queer Ecology: Identity and Field Research

In celebrating Pride Month, it’s crucial that we not only elevate and celebrate the voices and contributions of queer scientists, but also acknowledge and address the specific obstacles they may encounter in their professional journeys. As we embark on the third and final part of our queer ecology series, we turn our attention to the unique challenges faced by queer field biologists.

Queer field biologists often navigate a complex landscape, both literally and metaphorically. From conducting fieldwork in regions where their identities may not be accepted, to overcoming biases in academic and professional spaces, these scientists demonstrate remarkable resilience in their pursuit of understanding the natural world.

The Queer Workforce in STEM

In the realm of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), the presence of queer individuals is more significant than one might initially presume. According to a recent study, approximately 3.5 percent of Americans, encompassing about eight million people in the nation’s workforce, identify as part of the queer community.

However, this statistic doesn’t fully capture the reality of the situation within the STEM community. More than 40 percent of queer STEM workers haven’t disclosed their identities to their colleagues, coworkers, or students. This lack of disclosure is not without reason, as the challenges faced by queer individuals in these fields can be substantial and multifaceted.

But pressure to stay ‘in the closet’ can lead to negative consequences to both mental health and productivity. Closeted individuals spend a significant amount of cognitive energy engaging in preoccupation and vigilance to make sure that others do not suspect they are queer. This can result in feelings of guilt, shame, demoralization, and depression, which have behavioral repercussions, including tendencies to avoid social situations and the weakening of close relationships. Staying in the closet, therefore, exposes queer scientists to unnecessary cognitive demands—and emotional and psychological harm—when their main goal is to collect quality data.

This issue is not just a matter of personal struggle; it also has tangible impacts on productivity and career progression. A recent study found that queer scientists who did not disclose their identities in professional settings authored fewer peer-reviewed publications. This suggests a concrete productivity cost associated with the nondisclosure of a queer identity.

These challenges affect all queer workers in STEM, but they can compound the unique challenges faced by field biologists. Field biologists often work in remote locations and close-knit teams, where the pressure to conform and the fear of ostracization can be particularly intense. Moreover, they may have to navigate local cultures and laws that are less accepting of queer identities. Thus, while the STEM community as a whole needs to do more to support its queer members, there is a particular urgency for improvements in the field of wildlife biology.

Traveling for Field Research

Field biologists, in particular, face a unique set of challenges due to the nature of their work. Often, their research requires them to travel to regions where LGBTQ rights are minimal or non-existent.

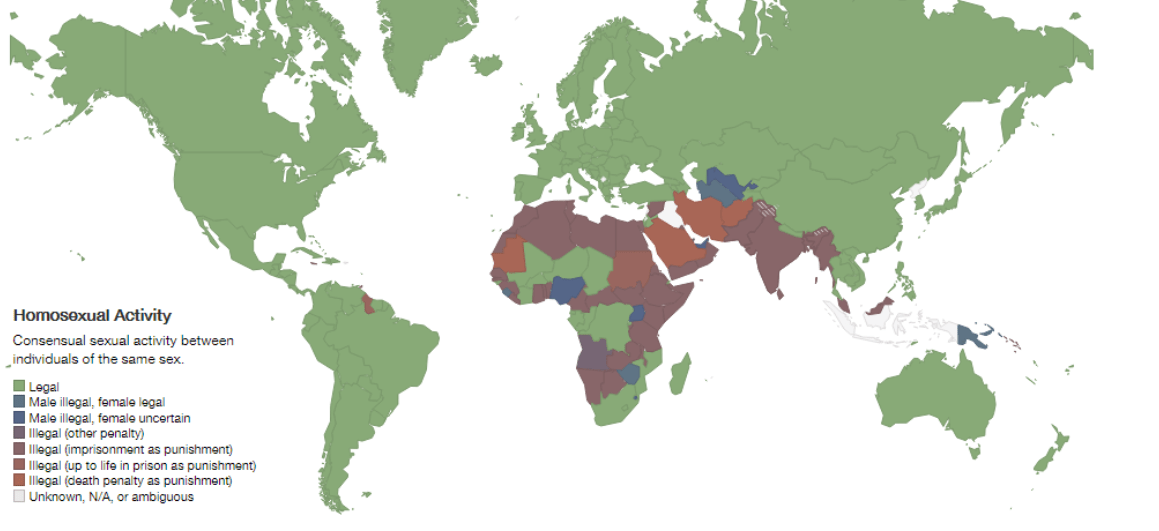

The risk of being out in the field is highly dependent on the location of the fieldwork. In some countries, queerness is illegal and can lead to capital punishment. Homosexuality, for instances, is currently illegal in 73 countries and punishable by death in eleven.

Even in countries where being LGBTQ is legal, local views and customs can make it unsafe or difficult for queer scientists to be out. Field biologists often need to establish close relationships with locals to obtain permission to perform their research in a specific location or to employ locals to aid in data collection. If local stigma against queer people is strong, the discovery that a queer scientist is in a research group can result in locals’ refusal to help the scientists or allow them to complete their research.

Dr. Christopher Schmitt, a gay primate biologist at Boston University, had a personal experience that highlights these challenges. He chose to leave his fieldwork in Gambia early due to anti-gay sentiment, culminating in presidential threats to slit the throats of any gay individuals. As a result, he was unable to collect a month’s worth of crucial, time-sensitive data. Such situations result not only in personal setbacks in terms of career progress, but also blocks critical science from getting done.

Traveling as a Transgender Biologists

Transgender field biologists face a unique set of challenges when traveling for fieldwork, particularly in regions where their identities may not be accepted or understood. These challenges can range from logistical issues to personal safety concerns.

One of the most immediate challenges is dealing with documentation and paperwork that could potentially out them. This includes passports, visas, and other official documents that may not reflect their affirmed gender. This discrepancy can lead to uncomfortable and potentially dangerous situations when crossing borders or dealing with authorities.

Access to transition-related medication can also be a significant issue. Many transgender individuals rely on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) as part of their transition process. However, these medications may not be readily available or even legally sold during the months they must be in the field. HRT also requires refrigeration, which may not be an option at remote field sites. This lack of access can disrupt a trans person’s medical regimen and potentially impact their physical health in addition to their mental well-being.

Medical services in general can be difficult to navigate. In areas where being transgender is stigmatized or misunderstood, transgender individuals may face refusal of necessary medical services. Alternatively, they may avoid seeking medical help for fear of outing themselves to a healthcare provider, which can result in untreated injuries or illnesses.

Finally, transgender field biologists may find it difficult to return to previous field sites after physically transitioning. If they were known at these sites before their transition, they may be unable to hide the changes they’ve undergone. This can lead to uncomfortable or unsafe interactions with previously established contacts and may even jeopardize their ability to continue research at these sites.

Challenges in Domestic Field Work

The challenges queer people face are not limited to international travel; the common conditions of biological field work can be oppressive to queer folk in any place, including the United States. These often involve several months living and working with up to dozens of other biologists from around the world, often in remote and rural areas or camps.

The remote and highly-competitive nature of many field jobs can, unfortunately, make it easier for people to get away with harassment. If a queer individual finds themselves being harassed by their co-workers, they may not feel comfortable disclosing the harassment to the primary researcher for fear of ‘causing problems’ or otherwise jeopardizing their professional peer-mentor relationship. What’s more, the strictly-planned and remote nature of field work can make firing technicians, finding replacements, or otherwise punishing hostile behavior logistically difficult, meaning harassment may go unpenalized even if primary researchers sympathizes with the victim.

If a queer person finds themselves in the presence of bigoted co-workers, they may choose to keep closeted. When required to live and work with these people in close-proximity, often without access to transportation, they may have no opportunity to be their authentic selves for several months at a time. This constant vigilance and self-censorship can take a significant toll on their mental health and overall well-being.

All in all, the challenges faced by queer field biologists—whether domestic or international—are multifaceted and complex, ranging from logistical issues to the psychological toll of dealing with bigotry and harassment. These challenges underscore the need for greater awareness, understanding, and support for queer individuals in the field of biology.

The Value of Queer Ecology

As we conclude our queer ecology series, we hope that you’ve gained a deeper understanding of this beautifully complex field and a profound appreciation for the unique perspectives, authenticity, and resilience of our queer scientists.

Embracing queer ecology is not merely about inclusivity; it’s about fostering innovation and promoting a more comprehensive understanding of our world. It challenges long-standing assumptions and harmful traditional ideologies, broadening our perspectives and deepening our appreciation for the complexities of nature.

But perhaps most importantly, queer ecology serves as a powerful reminder that the richness of our natural world is mirrored in the diversity of those who study it. That this diversity of perspectives, experiences, and identities is not just a strength—it’s a necessity. As we move forward, let’s continue to celebrate, learn from, and stand with our queer scientists. Let’s embrace the changes in perspective that enhance our understanding of the world and our place in it. And finally, let’s strive to create a scientific community that is as diverse and vibrant as the world it seeks to understand.

Read Part 1: Relationships to Nature and Part 2: A Spectrum of Perspective of our Queer Ecology series.