We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

A Mountain Lion in Hollywoodland: Does Los Angeles Appreciate Its Wild Animals?

Some passerbyers, however, are curious enough to ask what in the heck he is doing.

“Tracking a mountain lion,” he replies.

Probably not the answer most expected. Yet for those who inquire, not a single person—even the woman walking two adorable but admittedly in cougar country, vulnerable corgi dogs—express fear. Responses range from “cool,” to “wonderful that he is here,” or “can I see him?”

The puma, known as P-22, would only have to travel another six miles to stroll down Hollywood Boulevard. Ten million people annually visit the park (over double the visitation to national parks like Yosemite and Yellowstone), and they play golf, attend concerts at the Greek Theater (with acts like Mumford and Sons and Crosby, Stills, and Nash), hike or camp, or play a round of golf or tennis.

All while a mountain lion might be wandering in their midst.

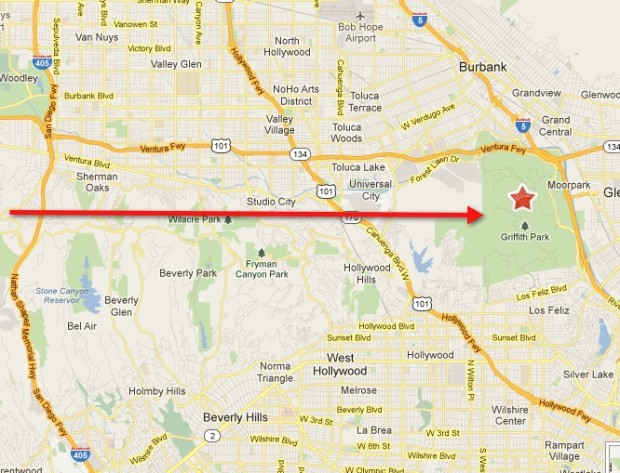

Because of genetic testing we know P22 journeyed to Griffith Park from the Santa Monica Mountains—and will probably journey back someday in search of a mate. A glance of a map quickly highlights that this intrepid cat had to cross not only a wide swath of developed areas in a major urban region, but he also made it safely across two major highways, including the worst highway in the country—the 405. I drive on the 405 frequently and barely make it out alive in a car.

Because of genetic testing we know P22 journeyed to Griffith Park from the Santa Monica Mountains—and will probably journey back someday in search of a mate. A glance of a map quickly highlights that this intrepid cat had to cross not only a wide swath of developed areas in a major urban region, but he also made it safely across two major highways, including the worst highway in the country—the 405. I drive on the 405 frequently and barely make it out alive in a car.

Griffith Park is merged with the urban experience, a hybrid of city and nature. No park boundary does or is going to contain P22, and if he decides to start dining on the pets of homeowners who live in the adjacent neighborhoods, or attacks one of the ten million people jogging or biking in the park, his welcome is likely to end very quickly. So far he seems to be figuring it out and limits his meals to deer and other animals. And except for the remote camera that detected his presence, no-one aside from researchers like Sikich have actually seem P22.

“So far, he has adapted really well to urban living and what it takes to stay alive—which is to stay out of sight and not to dine on the backyard dogs.”

Walking through Griffith Park with Sikich and seeing the close proximity of urban life, I became even more admiring of the Angelenos initial welcoming of P22.

Walking through Griffith Park with Sikich and seeing the close proximity of urban life, I became even more admiring of the Angelenos initial welcoming of P22.

Most of the 10 million people who visit the park and the almost 10 million people who live in Los Angeles County haven’t had much need to develop a relationship with mountain lions. You might worry about road rage inflicted drivers or being mugged on Hollywood Blvd, but a (wild animal) predator roaming your neighborhood isn’t something you previously needed to consider for day-to-day LA living.

Which brings me to the title question: does Los Angeles appreciate its wild animals?

I’ve been working on a book, When Mountain Lions Are Neighbors, Wildlife in Today’s California, and have been considering our relationship with animals across the Golden State. So I was excited (and honored) to be invited to participate on a panel on August 9 to consider if Angelenos value wildlife. Hosted by Zócalo Public Square and moderated by Kathryn Bowers, coauthor of Zoobiquity: The Astonishing Connection Between Human and Animal Health, the panel also features City of L.A. Animal Services wildlife specialist Greg Randall, and Natural History Museum environmental educator Lila Higgins.

As panelists, we’re being asked to consider questions such as how do the wild neighbors with whom we share our city affect our urban experience and the way we see the world around us? And what happens—to animals both human and non—when our most strident efforts to tame the world around us fail? Why do we love the wild animals of L.A. and what do they mean for life in our city?

Watch a video of P22 courtesy griffithparktrailcam.com:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=62ypylwysQM[/youtube]

Wildlife. Nature. People don’t typically associate these terms with Los Angeles, the stereotypical images being a smog-filled, disjointed urban sprawl of a city intersected with what seems like endless freeways of perpetual traffic jams.

Stereotypes can reveal some truth, but we also know Los Angeles as home to diverse people and communities, an urban land filled with greenscapes, and a remarkable array of wildlife. A river, albeit now with concrete banks, does run through it, and bears, bobcats and coyotes along with mountain lions roam within the city boundaries.

Surprised? Most people—even some who live in LA—are not aware of the immense connection the city still retains to the natural world.

Yet Los Angeles has made nature its own, woven its own unique cultural landscape onto the physical one, perhaps shaping the tale of Mother Nature into a structure it’s comfortable with, that of a Hollywood blockbuster screenplay. Jenny Price, author of the brilliant essay, Thirteen Ways of Seeing Nature in LA writes: “The history of L.A. storytelling, if more complicated, still basically boils down to a trilogy. Nature blesses L.A. Nature flees L.A. And nature returns armed. “

Isn’t the story of P22 the stuff of which blockbusters are made? It’s the puma version of Star Wars, or Rebel Without a Cause—“a rebellious young man with a troubled past comes to a new town, finding friends and enemies”—with maybe a bit of The Big Lebowski thrown in. And what better setting than Griffith Park, where scenes from Rebel were actually filmed and a statue honoring James Dean stands next to the Observatory.

Yes, I think the people of LA appreciate their wild animals. Perhaps not in the same manner people appreciate and relate to the vast bison herds of Yellowstone, or the grizzly bears in Alaska, or for that matter how most of us are taught to value wildlife, larger than life creatures standing in pristine and glorious nature scenes reminiscent of an Albert Bierstadt painting.

Wildlife just isn’t about idyllic nature settings, or science or environmentalism, it’s about art and culture and history and spirituality and peregrine falcons nesting on skyscrapers (the famous Union Bank pair), coyotes trotting through neighborhood backyards (everywhere), endangered butterflies living at international airports (El Segundo blue butterfly at LAX), and black bears stealing meatballs from trash dumpsters (The Glendale Bear). In Los Angeles, wildlife is about co-existence, about human and non-human residents sharing space and adapting to life together in this grand metropolis. A coexistence that is fraught with difficulty, that doesn’t always have a happy ending, especially for the wildlife (don’t fret-just wait for the sequel), but that ultimately can be beneficial to all.

In this new age of urbanism—95% of California’s population lives in urban areas–I think this style of co-existence evolving in Los Angeles might just be the new zeitgeist needed for the future good of both wildlife and people.

Truly, it’s something to celebrate that the city that gave us Carmageddon and Sharknado also allows a mountain lion to thrive.

Join the conversation! Zócalo and NWF invite you to attend the free event “Does Los Angeles Appreciate Its Wild Animals?” on August 9th at 6:00 pm at Grand Park in LA. For more information and to make your reservation visit the event website.

Follow NWF California on Facebook for more great wildlife stories and photos from across the Golden State!