We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Saving the Land and Water Conservation Fund is about Saving Culture & a Way of Life

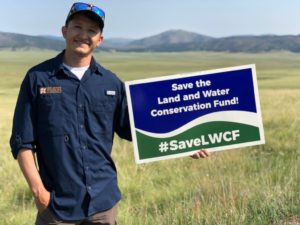

By Guest Author: Jeremy Romero

Being a sportsman and conservationist, I have seen firsthand the declining numbers of young hunters and anglers. I recognize the importance of getting younger generations into the field, passing down traditions and encouraging a way of life that values our public lands and caring for our environment. It is a task I take great pride in.

This August, I was fortunate enough to do just that with David, a 10 year old New Mexican, as I had the honor to take him and his father, a combat veteran, out onto our public lands for David’s first pronghorn antelope hunt. David, a 10 year old native New Mexican, received the license for a muzzleloader pronghorn antelope hunt on the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument through a New Mexico Department of Game and Fish program where individuals who draw tags can then donate them through a non-profit to youth, veterans and first responders. This amazing program continues to benefit youth and those that put their life on the line for us, with a chance to hunt some of New Mexico’s most iconic game species. In this case, David was the lucky recipient. With the school year rapidly approaching, David only had two days to hunt.

Seeing and experiencing the excitement David shared before we even set out made the hunt an immediate success. As a teacher, I pride myself in sharing with David the many ways we could hunt antelope. On the first day, we crawled and stalked numerous antelope only to have the fastest land mammal in North America quickly show us why harvesting a antelope would prove to be difficult. After setting up camp on the first night and telling great stories around the fire, we decided that the next day we would sit at a waterhole, realizing we needed to change strategies as we were no match for to the speed of the antelope. We knew that this would be a game of patience. Our plan was to wait and to hope that a thirsty antelope would make its way to water.

On the morning of the second day, as the sun rose on the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument near Taos, New Mexico, David sat ready for an antelope to approach the watering hole.

Learning to be still, to be quiet and listen, and to be patient and persistent is a valuable lesson that all of us hunters, including David, must truly learn to be successful. Yet, these lessons and cultivated skills do not stop with hunting.

I have learned that they apply to my work in conservation, as I have had to show this same quiet patience and persistence as I have worked to protect our national monuments and encourage communities to support the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF). Sitting as the sun rose that cool morning, I was reminded of these important lessons as I waited with David on the national monument in an area that received funding from LWCF to protect migration corridors and wildlife habitat.

Quietly waiting as the antelope approached, and with a technique as if it were straight out of a hunter education course, David successfully placed his cross hairs on the antelope. Taking a deep breath and with full confidence, David harvested his first antelope buck. It was a beautiful moment as I got to experience a truly sacred moment between David and his father —a moment I once shared with my own father and, God willing, I look forward to one day sharing with my child.

Like David, as a young child I too had been fortunate to have the opportunity to step out and explore some of the most beautiful places in the Southwest. Growing up in New Mexico, hunting, fishing and learning how to provide for myself and family were common lessons passed down from generation to generation. Living in an area where nearly 45 percent of the state is made up of public lands, I have been lucky to experience firsthand how these lands provide for myself, my family, my culture and a way of life.

Having land that protects my way of life and culture is just as important, if not more, than having a successful hunt or day on the water. As mentioned, a little known program called the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) has proven itself successful time and again in providing public access and promoting outdoor opportunities in many of America’s most special places.

In fact, many of the public lands I call home have been made accessible or improved as a result of LWCF. For example, some of my best memories growing up were sitting, listening, and watching hundreds of elk at what is now called the Valles Caldera National Park Preserve. At the time, the Valles Caldera was private ranch where one could only enjoy the scenery from the side of the highway. In 2000, $101 million dollars from LWCF was used to purchase the 80,000-acre Valles Caldera. This investment paved for public access and new opportunities to hunt and fish on lands previously inaccessible. Thanks to LWCF, my dreams of stepping foot in the National Preserve finally became a reality.

It’s undeniable the impact that the Land and Water Conservation Fund has played a role in preserving traditions passed down from generation to generation. Many people do not know that the LWCF was also used to acquire more land within the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument where David and I embarked on his first hunt. This fund allowed for increased access so new and upcoming hunters and anglers have a place to reconnect with the land, water and wildlife like the many of generations before David have done.

LWCF isn’t an abstract federal program or meaningless acronym. For sportsmen and women, the Land Water Conservation Fund stands for our culture, our identity and our way of life. Without LWCF, we could lose the opportunity to pass down the story of dreams coming true not just for us, but for the many generations to come. In essence, LWCF does not just create public access and new opportunities for sportsmen today; it creates within in each of us a sacred bond with one another and a deep connection to our culture, wildlife and the land that in New Mexico and much of the American west tells a story that has been at work for thousands of years.

Sadly, the Land and Water Conservation Fund expired this past September. I encourage you to contact your congressional members and ask them to permanently reauthorize and fully-fund LWCF. Tell congress that by doing this they won’t just be saving one of America’s most successful conservation programs, they would be ensuring that future generations have transformative opportunities to engage in outdoor recreation and to reconnect with themselves, their culture, their history and the sacredness of our public lands, water and wildlife.

READ MORE