We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

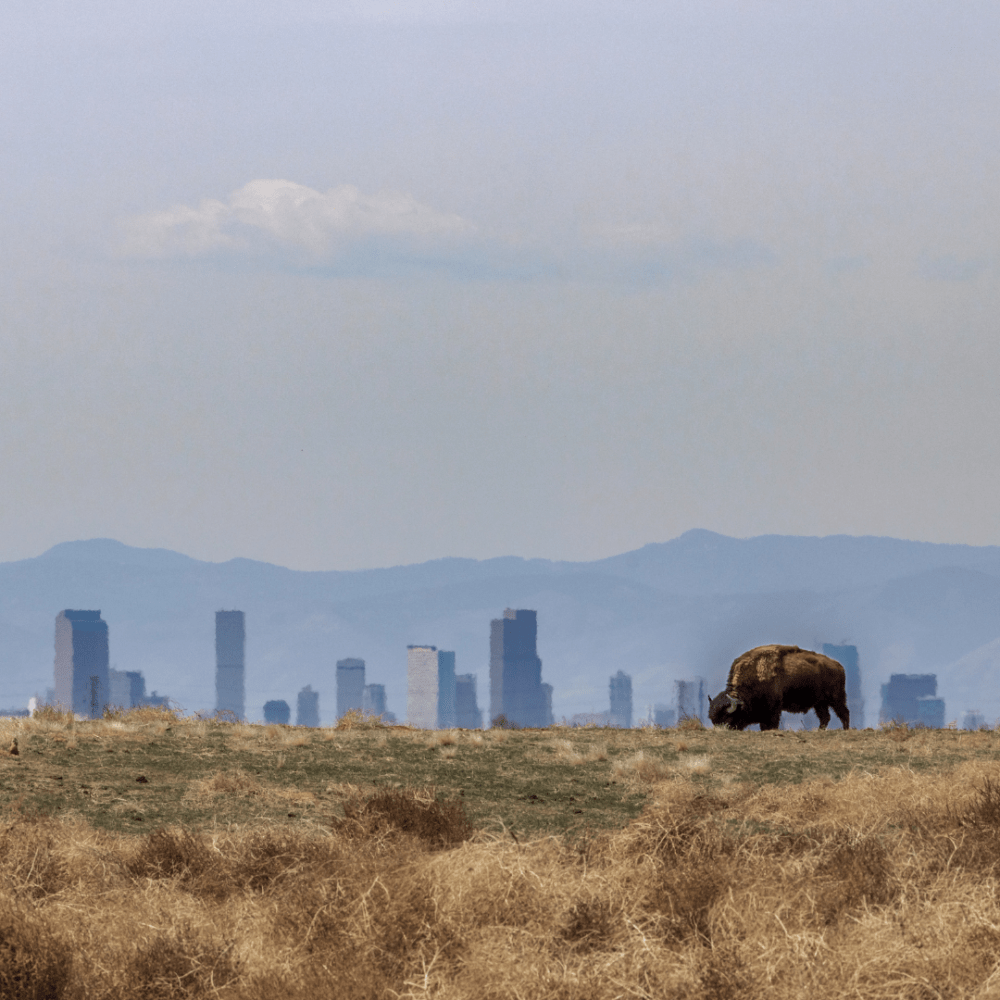

Beavers, Trout, and a Changing Climate

Research seeks to ensure beaver-related stream restoration is a boon rather than a bother for native trout

Driving through the lush forests of America’s Pacific Northwest, you might spot this bumper sticker: “Beaver taught salmon how to jump.”

Beavers may seem magical, especially when their engineering feats are capable of boosting stream flows, providing green refuges during wildfire and drought, and creating more habitat for birds and other wildlife. But that doesn’t mean these rodents are actually capable of instructing fish how to leap.

Instead, the bumper sticker refers to the fact that North American fish species co-evolved with the continent’s largest rodent. Salmon and trout have adapted to jump over or swim around beaver dams. In return for the extra effort navigating upstream past dammed waterways, native fish benefited from the bountiful food and shelter created by beaver ponds.

Today, though, both furry and finned creatures are facing a new “normal.” Populations of native salmonids and beavers have declined drastically due to human influence. In addition, climate change has further reduced the water quality and flows in headwaters streams where native trout reproduce. As their habitat dwindles, it may mean that fish are in trouble if certain tributaries are blocked by a natural barrier. This has sparked concerns about whether beaver dams are always in the best interest of wild trout.

Beaver-related restoration—such as reintroducing beavers or building mimicry structures like beaver dam analogs (BDAs)—has gained momentum as a low-cost, highly-effective watershed restoration practice. To better understand the effects of natural and simulated beaver dams on native fisheries, University of Montana PhD student Andrew Lahr is researching several streams in western Montana.

“We need more research on exactly how beaver ponds impact fish so we can make confident, science-based decisions moving forward,” says Lahr, who worked with Clark Fork Coalition, Lolo National Forest, and The Nature Conservancy to design and install his study.

A boom in beaver-related restoration

Natural and simulated beaver ponds help slow down the flow of water, providing natural water storage and flood control. The ponds recharge groundwater, which keeps streams running when rain and snowmelt are scarce. It also spreads water across the floodplain so it can grow more green plants that feed terrestrial wildlife and livestock.

Fish get to join the feast, too, since beaver ponds diversify stream habitat and produce more aquatic plants and insects. Plus, the side channels, sloughs, and meanders created by dams add complexity to stream habitats, giving fish more places to hide, rest, or spawn.

Because of these promising ecological results, beaver-related restoration projects have increased markedly over the past ten years. In fact, these projects have become so popular that their implementation has outpaced the science on how more natural and simulated beaver structures are affecting fish and other wildlife.

“On the whole, fish benefit from beavers and their ponds. The trick is to make sure we choose the sites wisely and make sure they benefit the whole aquatic community, including wild trout,” says Ladd Knotek, a fisheries biologist with Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks who helped tailor Lahr’s research project.

Low flows impede trout

Knotek says that the majority of beaver-related restoration projects are not a problem for native salmonid species. However, Montana only has a few remaining streams where pure (non-hybridized) cutthroat trout, arctic grayling, and bull trout thrive. These strongholds are areas where fisheries biologists worry that new in-stream structures might unintentionally impact native trout populations because these species can no longer adapt easily to habitat changes.

“One hundred years ago, beaver dams weren’t an issue. If a dam was too high or there was no way through, the overall population was fine because the species was widespread. But we don’t have that population resiliency anymore,” explains Knotek.

Bull trout are listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act, and require very clean, cold water to thrive. Their remaining spawning habitat (small tributaries where they lay eggs each fall) has dwindled to just a handful of mountain headwater streams.

Due to hotter summers and human water use, many streams have precariously low flows—or even dry up—by the fall. That means there might not be enough water in the creek anymore for bull trout to traverse a beaver dam to spawn like they used to.

Although native cutthroat trout head upstream to spawn in the spring, they also migrate in the fall in search of deep, protected pools that will stay ice-free all winter. A poorly-placed beaver dam or BDA may inadvertently block their path to safe overwintering habitat.

Part of Lahr’s research includes analyzing the movement of westslope cutthroat trout in the headwaters of Lolo Creek. He will tag several individuals this summer to track whether they can move over or around dams. A similar study led by Utah researchers is also underway on the Bitterroot River to determine how bull trout are interacting with beaver dams.

“We want to fine-tune beaver mimicry projects based on this research to make sure they’re done in a way that’s compatible with the life cycle of native fish,” says Knotek.

Science-based answers on how beavers affect trout

Another pressing question for fisheries biologists is whether natural or simulated beaver ponds give non-native trout a competitive advantage. Introduced species like brook, rainbow, or brown trout tend to fare better in warmer water—such as ponded habitat that heats more quickly than flowing water. That may give non-native trout an advantage in beaver ponds, allowing them to outcompete native trout for food and other resources.

“We know that beavers add habitat complexity in the stream, which increases the carrying capacity for all fish species. The question is do they disproportionately benefit non-native trout?” says Knotek.

Lahr’s research aims to answer the question by determining if westslope cutthroat trout are being displaced by brook trout because of beavers. Although evidence shows brook trout proliferate in beaver ponds, no statistically significant research has shown that cutthroat populations decrease in response.

Instead, Lahr wonders whether beaver ponds are able to hold more fish of all species, supporting native and non-native trout equally.

“When you add beavers to the mix, models predict that westslope cutthroat trout persist and have higher growth rates because there’s more food, more plants, more water,” says Lahr.”And that translates upstream as you leave the pond, too.”

Lahr points to a recent study conducted in Oregon that showed beaver ponds actually lowered overall stream temperatures during the summer because of the increased exchange of cold groundwater.

“There’s a chance that beavers may create true climate resilience for trout in Montana,” adds Lahr.

The National Wildlife Federation continues to help answer questions about the effects of beaver-related restoration projects. In north-central Montana, NWF and its partners are monitoring recently-built beaver mimicry structures to test if structures enhance habitat for sage grouse and improve prairie streams. This ongoing research will compare water temperature, instream habitat, wildlife diversity, and riparian vegetation in restored versus un-restored sites.

“Since this type of restoration is relatively new in the prairie grasslands, we want to make sure beaver mimicry projects are paying off for people, wildlife and fish alike,” says Sarah Bates, deputy director of NWF’s Northern Rockies, Prairies and Pacific Region.

Visit our regional website to learn more about NWF’s work to restore habitat for beavers and other species.

Our work for wildlife—from beavers to native fish—is supported by the generosity of wildlife advocates like you. Please consider supporting our work today.

Donate!