We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Heating Up: Climate Change Harms Alaska’s Communities & Wildlife

Rising temperatures in the Bering Sea could disrupt fisheries and are linked to massive seabird die-offs, shifts in the local ecosystem, and hardship for Alaska Natives.

In 2019, seabirds off the coast of Alaska’s Bering Sea suffered massive die-offs for the fifth consecutive year. Over 9,000 birds washed ashore along the Alaskan coast between May and August. Short-tailed shearwaters were among the most affected birds, but puffins, murres, and auklets washed up as well.

Climate change is likely a contributor to these die-offs. The affected seabirds, whose deaths are consistently found to be caused by starvation, rely on cold water-dependent prey such as zooplankton and certain fish populations. Unfortunately, the local, historically ice-dependent ecosystem is shifting and these cold water-dependent prey species may not be as available as they once were.

Sea surface temperatures have risen in the Bering Sea. Concurrently, since 2010, the region has seen an increasing abundance of generalist fish species from southern ecosystems, while sentinel species, like Arctic cod, have been shifting to northern habitat. Even if seabirds are able to adapt to these changes and catch new prey species that move into the area, the warmer water species are likely to be less nutritious than fatty, cold water fish.

“I remember going kayaking in 2015 when Common Murres were washing up in droves on the beaches. Scavengers would eat the only breast meat and the heads, so you would see overwhelming numbers of just the skeletons with feathered wings and feet still attached. The sight of so many Murres floating dead in the water was heartbreaking,” — Matthew Jackson, Alaska resident and Climate Organizer for the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council.

The sight of so many Murres floating dead in the water was heartbreaking.”

— Matthew Jackson, recalling 2015 coastal kayaking excursion.

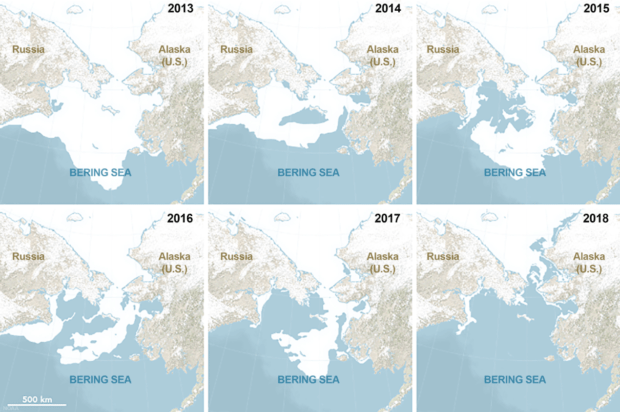

Rising sea surface temperatures also mean that Arctic sea ice is forming later and at a lower extent. In 2018 and 2019 the sea ice extent in the Bering Sea only reached about half of what is normal for winter conditions, and the 2017-2018 winter marked the lowest winter maximum sea ice coverage on record. This is perhaps the start of a pattern that climate models predict will become common in the 2030s.

Throughout the fall and winter months, sea ice extent plays an important role in the balance of the Bering ecosystem and in the lives of the indigenous communities along Alaska’s coast. And the spring melt facilitates algal blooms, allowing the growth of biomass, which forms the base of the Arctic food chain. Copepods and other small creatures rely on the spring algae for sustenance. These small creatures are prey for species such as Arctic cod. The cod feed seals, polar bears, and other marine mammals, and help fuel Alaska’s multibillion-dollar seafood industry— an industry that creates almost 100,000 full-time jobs per year.

Elders from eight indigenous communities along the Alaskan Coast discussed the impacts of rising temperatures and the shifting ocean ecosystem in a report entitled “Voices from the Front Lines of a Changing Bering Sea,” which appears as a direct contribution to NOAA’s 2019 Arctic Report Card. The report chronicles some of the challenges faced by Alaska Native communities including the loss of sea ice that is crucial for travel routes between communities, increased difficulty hunting marine mammals as the Arctic ecosystem shifts northward and prey for mammals becomes less abundant, and more severe erosion as winter storms batter shorelines without sea ice to abate incoming wave energy.

Carol Oliver, a Council Member of the Chinik Eskimo Community Traditional Council, says of Golovin, Alaska in the report, “Golovin as a coastal community is being affected very quickly by the storm surges, by erosion. In the 90’s, we had to move our airport up on the hill because, even today it is flooding, and the old airport is being covered with water right now… Within the last few years, we’ve been encouraging our people to build on higher ground; to be out of the floodplain.”

The unprecedented changes to the Bering Sea ecosystem, as well as the impacts on local communities and Alaska fisheries, are linked to climate change and will likely continue without swift action. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, Alaska has been warming twice as fast as the global average since the mid-twentieth century. And, this January Arctic sea ice extent was below average in parts of the Bering Sea and well below average on the whole. This March when sea ice extent reached it’s yearly maximum, it was the eleventh lowest in the 42-year record.

Heightened temperatures and diminishing sea ice off the coast of Alaska are just two of many indications pointing to the urgency of addressing the climate crisis head-on. The consequences and costs of natural disasters are rising around the U.S. as seen in the National Wildlife Federation’s interactive Unnatural Disasters Story Map. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, global CO2 emissions need to be cut to nearly half the current level by 2030 and to net-zero emissions (after accounting for carbon sinks) by 2050 at the latest to avoid the most severe impacts of climate change.

Investments in clean energy, energy storage, energy efficiency, electric vehicles, and carbon removal technology are key to reducing carbon emissions and meeting these goals. As well, investments are needed for “natural climate solutions,” which can both mitigate climate impacts through carbon storage and emissions reduction, and mitigate natural disasters through protective functions, all while providing other benefits like habitat creation or added recreational value.

One incredible example of a natural climate solution is the Tongass National Forest in Alaska, which is among the nation’s most important carbon sinks and supports 80 percent of the commercial salmon harvested in southeast Alaska. Natural climate solutions can have important job creation functions and economic benefits. Every million dollars spent on reforestation, land and watershed restoration, and sustainable forest management can create 39.7 jobs, compared with only 5.18 jobs per million dollars invested in the oil and gas industry.

This spring, important stimulus legislation may provide an opportunity to invest in natural climate solutions, clean energy, and energy efficiency. Stay tuned for coming action to get involved and advocate for these crucial rebuilding and protective strategies.

To learn more about how climate change affects natural disasters in your state, visit nwf.org/unnaturaldisasters. Or to learn more about using natural systems to ameliorate the climate crisis, check out our Natural Climate Solutions Federal Policy Platform at nwf.org/naturalsolutions.

This blog is a part of a series on climate impacts and climate-exacerbated natural disasters. More blogs in the series: