We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Softening Our Shorelines: Solutions for People and Wildlife Alike

A long history of coastal development, coastal erosion, and storm impacts has led to the armoring of our shorelines with sea walls, breakwaters, riprap, and levees. But, hardened shorelines can complicate coastal adaptation needs, alter natural ecosystems, and may be counterproductive in the face of sea-level rise and associated inland shifts. Living shorelines, in contrast, can enhance the capacity of coastal habitats and communities to adapt and respond to climate-fueled changes.

As more than 50 percent of the American population, about 164 million people, live or work in coastal counties—and climate-driven stressors threaten people and wildlife alike—living shorelines provide a solution that can protect human communities, while also fostering biodiversity.

What is a Living Shoreline?

Living shorelines are a natural alternative to “hard” shoreline stabilization methods and provide numerous societal and ecological benefits, including nutrient pollution remediation, essential fish habitat structure, and buffering of shorelines from waves and storms. Research also shows that living shorelines are more resilient than hard shoreline structures like bulkheads in protecting against hurricanes.

Living shorelines refer to a broad range of shoreline stabilization techniques that use vegetation, shellfish, or other natural resources—sometimes in conjunction with harder shoreline structures—to stabilize estuarine coasts, bays, and tributaries. Living shorelines typically help reduce shoreline erosion, while also enhancing habitat value, supporting natural coastal processes, and providing added storm protection. Examples of living shorelines include natural marshes, marshes with sills, marshes with oyster reefs and mangroves.

Research indicates that during Hurricane Irene, 76 percent of bulkheads were damaged along hard hit shorelines in the central Outer Banks; whereas, none of the marsh or marsh and sill shorelines suffered visible damage, loss of sediment, or loss of elevation. An analysis of research on the cost of materials also found that living shoreline costs range from $50 – $150 per linear foot, depending on the type of approach used. In contrast, this analysis determined that bulkhead costs range from $80 – $1200 per linear foot. Thus, natural infrastructure projects like living shorelines, which can restore vital habitats such as marshes and wetlands, are both commonsense and necessary.

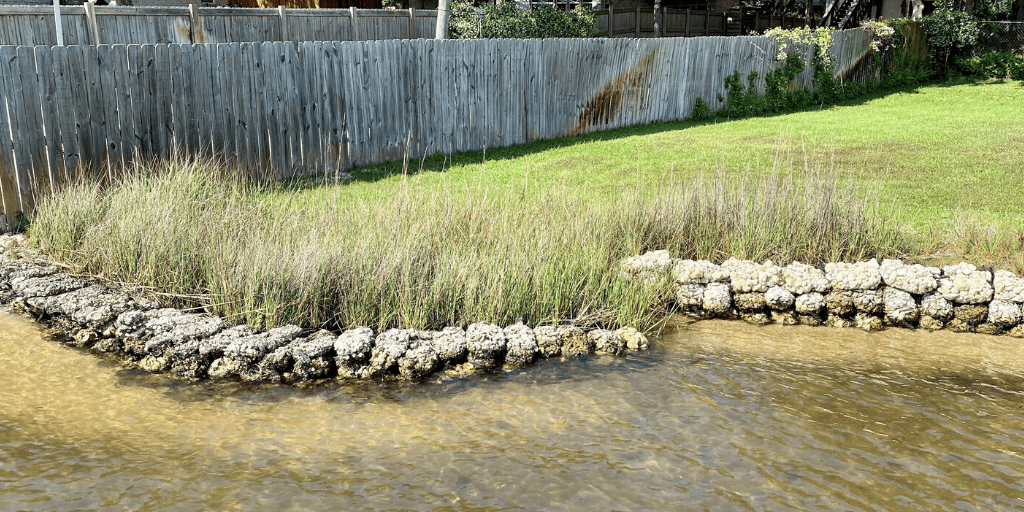

Jennifer McPeak, a resident of Northwest Florida, added that living shoreline projects are not only commonsense from a community resilience perspective, but can also be surprisingly affordable. McPeak developed a living shoreline in the saltwater bayou at her home that consists of reef breakwaters made of oyster shells bordered by cordgrass.

A Solution that Really Works

McPeak originally wanted to use a sea wall to combat the erosion she was experiencing along her shore. But, the sea wall would have cost $14,000 and required the loss of more shoreline to install. When the Florida Department of Environmental Protection agents came out to examine her shore, they asked if she had heard of a “living shoreline” and put her in touch with the Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance (CBA), a local non-profit responsible for sustaining healthy local waterways through monitoring, education, restoration, and research.

“I had never heard of [a living shoreline] before,” McPeak explained. “When you’re watching your biggest investment fall off into the ocean, that’s going to make you a little tense, and there was almost no information on [living shorelines].”

McPeak, however, was able to work with CBA’s restoration coordinator to learn more about living shorelines. After discovering both the economic and ecological benefits, she decided to “take the leap” and install one at her home—and she was not disappointed.

“I sort of fell in love with the idea that it would create this whole ecosystem, and we might actually see some accretion,” McPeak said.

Her living shoreline cost only $3,000, stopped the erosion, helped her gain back a large amount of sand and land, and created a blossoming ecosystem that she had never seen before.

“Going into this, I was totally ignorant … Our shoreline was just completely barren … so I kind of thought that’s how it was in this bayou,” she confessed. “As soon as we started protecting the shoreline and the grasses started growing … the life that came pouring back into this bayou was unreal. It became this fully real-life ecosystem, I mean almost immediately. It wasn’t something that took years and years to build up.”

All kinds of crabs, numerous types of fish like snapper and barracudas, stingrays, pistol and grass shrimp, eels, herons, and seahorses—to name a few—have all populated McPeak’s bayou since the living shoreline was developed.

McPeak emphasized that her living shoreline has also benefited local fishermen, who now frequent her bayou because of the abundance of marine life.

“They fish my shoreline because it’s the food chain brought back to life right there,” she said.

This flourishing ecosystem, however, is not just significant from an ecological standpoint. The living shoreline is also economically beneficial for both McPeak and her community, especially in terms of disaster mitigation.

Living shorelines like salt marshes not only protect against wave energy, but also capture the sand and soil deposited from storms, she explained. “Everytime we have a storm event, I’m like ‘bring it on’ now because that almost guarantees that the storm is going to leave sand on my shoreline, which means it’s raising the level of my shoreline,” she said. “So, as seas start creeping up, Mother Nature is very happily building almost like … a [natural] levee”

Every $1 spent on natural hazard mitigation saves the United States $6 in future disaster costs, making living shorelines a valuable investment, McPeak said.

“The value is insane; it’s so much better [than a sea wall],” she explained.

McPeak’s living shoreline also helps protect her community and its vital tourism industry by decreasing harmful algal blooms, which can shut down Florida beaches sometimes for weeks or months at a time. The cordgrass that she uses in her shoreline is a major nitrogen filter, helping to decrease the growth of algae and protect marine species that wash up onto beaches sick or dead because of the algal blooms.

“If you’re beating back those harmful algal blooms then you’re also protecting your local economy,” she said. “It’s good for business, too.”

McPeak emphasized that she is using a living shoreline because it doesn’t just work, but it works well and completely stopped the erosion. “I’m totally obsessed with it,” she said of her living shoreline.

McPeak noted, however, that the permitting process for her living shoreline was a challenge, taking nearly a year when the process for a seawall would have likely taken only 30 days. Fortunately, the permitting process in Florida for living shorelines has since sped up significantly, she said.

The prolonged permitting process is a commonly cited issue. In states where living shorelines are growing in popularity, new permitting processes and guidelines must be established for living shorelines to ensure that interested landowners are not deterred by a permitting process that is far more complicated than that for a seawall.

“The challenge for the homeowner is … when you make that decision that … this has gotten out of control, and we have got to do something about this, … you want to move [quickly],” she said. “And to be told it could take a year is horrifying.”

Current Status of Living Shorelines

The National Wildlife Federation recently released a “Softening our Shorelines” report that provides a state-by-state catalog of the current permitting process for living shorelines in Gulf and Atlantic coastal states. This report highlights challenges like those McPeak faced when installing her living shoreline, as well as ideas to improve the permitting processes.

“Softening our Shorelines” features opportunities to increase the appropriate use of living shorelines to promote resilience in coastal communities, stabilize shores, and support wildlife and ecosystem services. It focuses on the benefits of living shorelines for people and wildlife alike and examines the regulatory landscape for living shorelines to facilitate the transfer of best practices for natural solutions.

The report found that although living shorelines and natural infrastructure projects prove to have a myriad of societal and ecological benefits, the rate at which they are installed, compared to hard shoreline stabilization projects, is still relatively low due to challenges such as complicated or lengthy permitting processes and a lack of qualified contractors.

“Softening our Shorelines” illustrates that the regulatory and policy landscape is notably different from one state to the next and captures the detailed approaches taken by each. The report also emphasizes that both incentives, such as tax deductions and low-interest loans for living shoreline installations, and education play a major role in the popularity and accessibility of living shoreline approaches.

Recommendations at both the federal and state level were provided in the report to aid in the further growth of natural solutions like living shorelines. The recommendations include:

- Increasing federal investment in project implementation and monitoring

- Establishing a permitting preference for nature-based or hybrid designs

- Ensuring parity in the permitting process for living shoreline approaches, and

- Enabling disaster mitigation dollars to support living shorelines.

To learn more about living shorelines and natural infrastructure projects, as well as how permitting and implementation vary in each state, visit the report here.