We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Can Cities Capture Too Much Water?

New Report Provides a Pathway for Water-Conscious Communities to Keep their Rivers Flowing

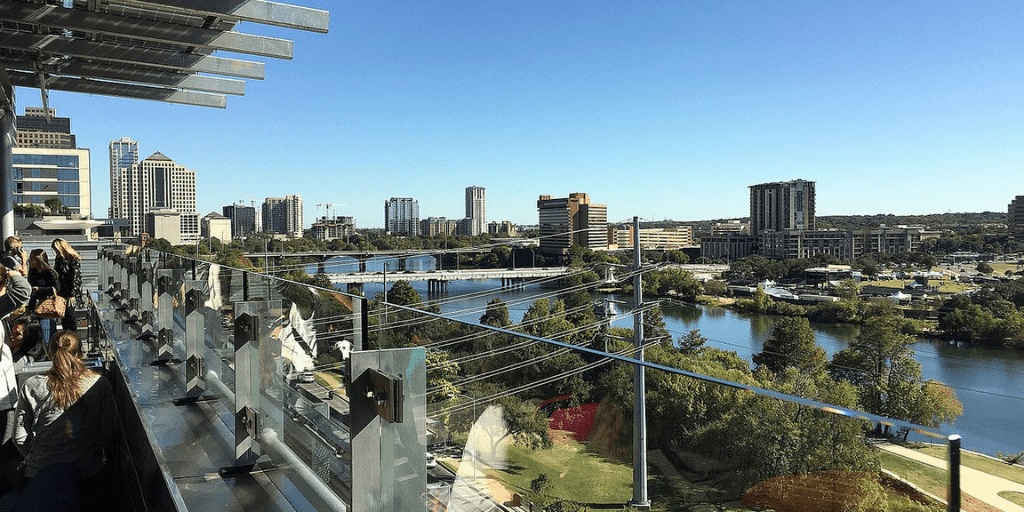

Returning items to circulation has more than one meaning at the Central Library in Austin, Texas. In addition to holding thousands of books (and seeds!), this much-celebrated community project captures everything from rainwater to air-conditioning condensate, storing and treating it for re-use onsite.

Projects such as Austin’s library are on the forefront of a nationwide push by innovative, growing cities to better use their own urban environment as a source of water. Yet, as forward-thinking cities become increasingly adept at capture and reuse, they also confront a related problem—capturing too much water can deprive rivers and streams of critical flow levels. It’s a classic dilemma of urban management in the climate-change era. Creative efforts to save water in one sector can lead to unintended consequences elsewhere.

In the particular case of reduced river flow, the scale of the potential consequences is staggering. River systems with a healthy flow of water have a portfolio of benefits that touch on nearly every level of human, animal, and plant life.

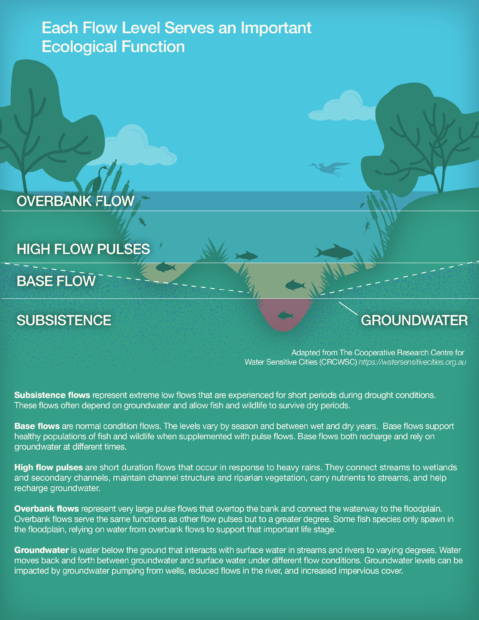

In a healthy system, seasonal flow patterns help drive the lifecycle of everything from aquatic bacteria to large fish to terrestrial wildlife species that range far from the main river channel. Robust river systems also amplify biodiversity (see the Amazon basin as the ultimate example of this dynamic) and provide much-needed seasonal wetting of soils and floodplain areas that support trees and birds. In addition, flowing water plays a critical role in diluting and assimilating contaminants that would otherwise accumulate and severely harm local ecosystems. At the subterranean level, healthy flows recharge the groundwater systems which enable life further afield.

Of course, human communities are deeply entangled in all the ecosystems sustained by healthy waterways. We depend on the same groundwater, we harvest countless riparian-dependent animal and plant populations, and we recharge our souls on and around these waterscapes.

Perhaps most critically, all these benefits are spread across, and dependent upon, a healthy, functioning watershed. Like a twist in a water hose, a permanent reduction in flow at any point on a waterway leads to considerable ripple effects on downstream communities.

City water planners are increasingly sensitive to these broader dynamics but have long lacked practical, informed guidance as to how to better incorporate healthy flow targets into established planning processes. Given the lack of guidance and the prospect of pandemic-induced budget constraints, the temptation for planners is to simply emphasize maximizing use of local water sources as the primary “eco-friendly” dimension of new projects. Yet, as we’ve seen, a string of thirsty cities attempting to capture as much water as possible will inevitably degrade the broader watershed.

Fortunately, a new report from the National Wildlife Federation, the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, and the Pacific Institute aims to address this growing quandary. The report provides water utilities and decision-makers a planning framework for integrating analysis and support of healthy waterways into city programs and projects. We offer planners both a step-by-step template and a best-practice toolkit—all intended to provide practical, actionable guidance culled from the experience of cities at the forefront of planning for healthy waterways.

Despite their presence in nearly every urban environment on earth, individual waterways are notoriously difficult for planners to define and quantify. Like water itself, waterways constantly shift, slide, merge, and change character. Precisely for this reason, we recommend water utilities seriously engage with a broad spectrum of people who live near and with their rivers—community members who walk alongside, boat, fish, and swim in local waters; advocates who want livable neighborhoods and a reliable water supply; area environmental scientists who have studied local flow levels and the specific ecosystems that depend on them. A sustained public engagement process that captures both lived experience and localized expertise can help produce water plans that better understand and prioritize the healthy flow of water through a community.

Of course, community-driven visioning is just the beginning of planning for healthy waterways. Water utilities also need practical guidance on which specific technologies in their expanding array of options can positively affect local flows while also contributing to bottom-line concerns over water supply and budget constraints.

Stormwater capture technology is one such versatile tool our report highlights for planners. As concrete and asphalt continues to spread across urban landscapes, stormwater that used to seep into local underground flows can’t penetrate the surface and is instead whisked away by artificial drainage channels. All this unabsorbed water causes a main river channel to momentarily surge with flood water in a manner out of sync with historic flood patterns. A creatively designed stormwater capture program can serve multiple beneficial purposes in such a situation. Not only can it help prevent flood surges by capturing elevated run-off, the water it captures can be used to boost local water supply, recharge groundwater, and replenish waterways during increasingly-frequent dry periods.

It is this kind of practical, mutually-beneficial approach our report seeks to emphasize. We want to offer cities a pathway to reconcile their growing ability to capture and reuse water with their continued need to maintain healthy, flowing waterways. Back here in Austin, our not-so-little library is remarkable not only for the circulation of recycled water inside its walls, but for the sparkling, languid gleam of the Colorado River just outside its windows. A vibrant, resilient world needs both kinds of flow.

To learn more about how cities can better plan for healthy waterways, check out the new report from the National Wildlife Federation, the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, and the Pacific Institute: Ensuring One Water Delivers for Healthy Waterways: A Framework for Incorporating Healthy Waterways into One Water Plans and Projects

For more on the innovative water capture and re-use system at the Austin Central Library, check out this helpful explainer.