We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Fencing for Wildlife

Combining data, relationships, and volunteers for on-the-ground impact

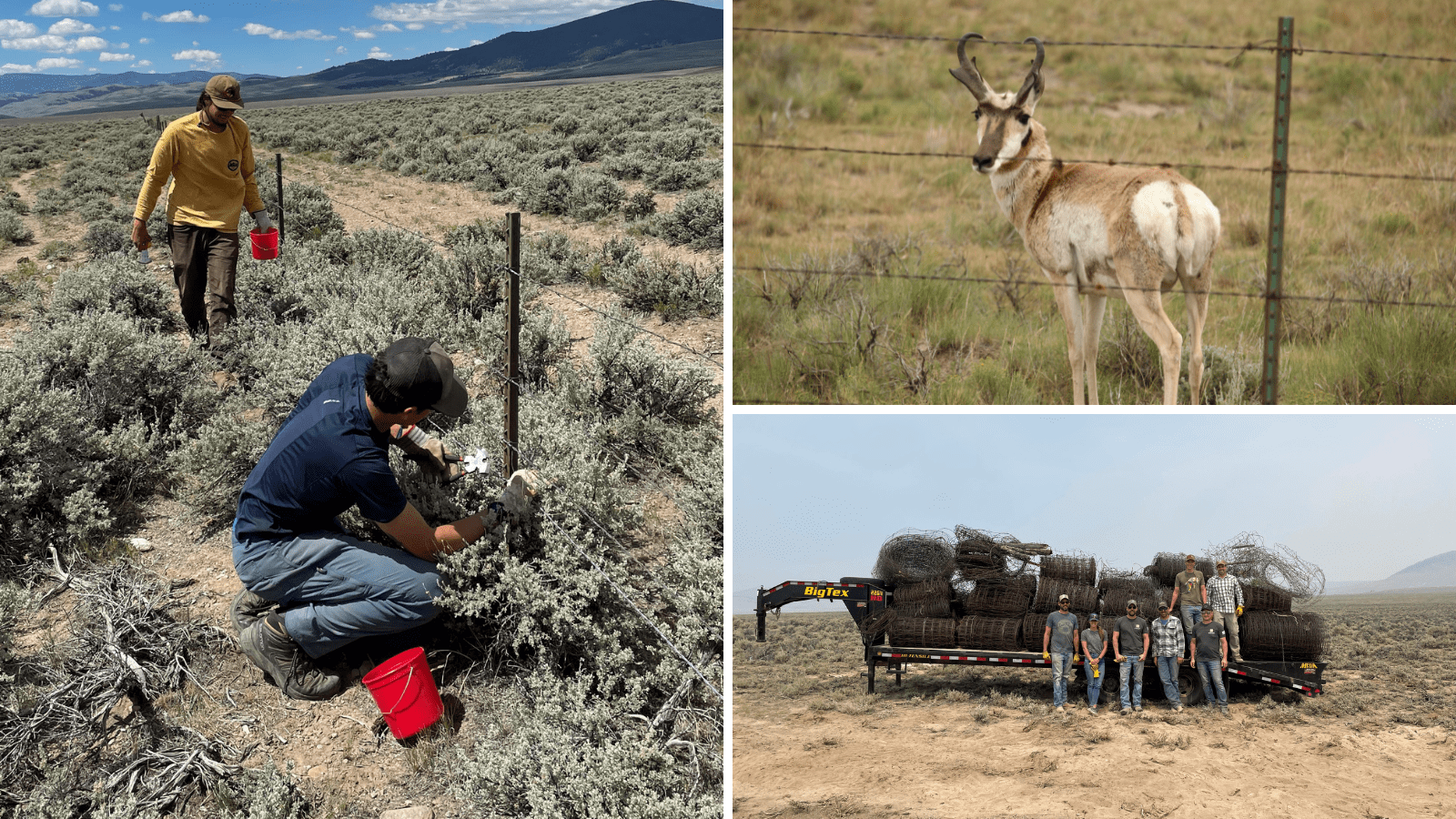

A force — 67 volunteers strong, hailing from 10 organizations — came together to facilitate pronghorn migration in southwest Montana.

“Working side by side, in the searing heat, we tackled a fractured landscape and over 5 miles of fences to introduce wildlife-friendly fencing…”

I reflect on this summer’s accomplishments by looking over my gear. The soles of my boots are peeling off. My chainsaw and loppers are dull. The bed of my pickup is covered with pieces of old barbed wire tangled in the wood dust of rotted fence posts. Then there’s the cooler that I stocked and restocked countless times with ice-cold drinks to keep volunteers moving in the heat. It’s now empty and drying in the sun. What does it all represent?

A force—67 volunteers strong, hailing from 10 organizations—that came together to facilitate pronghorn migration in southwest Montana. Working side by side, in the searing heat, we tackled a fractured landscape and over 5 miles of fences to introduce wildlife-friendly fencing.

There was a fair amount of advance effort to lay the groundwork before the fieldwork began to transform these fences to wildlife-friendly standards. First, as the coordinator of this project, I worked with partner organizations to identify the highest-priority locations for fence mitigation. We looked at maps of pronghorn GPS collar data to discover where a fence blocked or impeded movement. I then worked with landowners and public land agencies to develop work plans for specific fences that suited both the wildlife and the needs of landowners and lessees. Next, I needed boots on the ground, and volunteers heeded the call to provide the manual labor needed to get the job done.

We had an impressive showing of volunteers this summer, from local Dillon residents and regional sporting groups to college students from across the country. A small business owner and his staff drove all the way from Minnesota with their heavy equipment to help roll up miles of woven fence wire. When I exclaimed in disbelief that they had actually shown up he said, “Of course, we love doing this stuff.”

Barriers in the sagebrush

Pronghorn are thought to have evolved on the prairies and shrublands of North America locked in chase with fleet predators now extinct. Their survival tactics of speed and keen eyesight kept them out in the open and they didn’t develop a knack for jumping the way elk or deer did; species that survive in part by moving quickly through the timber.

So here we are, 20 million years later and pronghorn are the sole surviving member of a family of hooved mammals found only in North America (Antilocapridae). They are the second-fastest land mammal in the world after the African cheetah but they rarely jump fences.

Instead, pronghorn must find a way to crawl under or through them. This makes navigating the landscape difficult, especially in areas where fences have bottom wires near the ground. These fences were historically built to keep sheep and cattle contained and predators out of pastures. However, the proliferation of woven wire and barbed wire fences with low ground clearances has resulted in a landscape that is much more difficult — and often dangerous — for pronghorn to navigate.

Fences can cause direct injury to pronghorn and other species, and the likelihood of starvation may increase if wildlife can’t move to appropriate areas to find food. In northern latitudes like Montana, a key ingredient for pronghorn survival is the ability to move to areas with shallow snow depth to feed on sagebrush, their preferred winter forage. According to Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, the pronghorn population in the Horse Prairie area has been in steady decline since the mid-1990s and there’s no clear indication of why, but fences are likely a contributor.

The National Wildlife Federation is assisting pronghorn conservation efforts in southwest Montana by improving winter range habitat as well as ensuring that migration routes are barrier-free. Modifying fences with smooth bottom wires that are 16-18 inches off the ground creates the necessary gap for pronghorn to get under without being injured.

This clearance also helps juvenile elk and mule deer. They too have difficulty jumping and can get caught in the top wires of fences during unsuccessful crossing attempts. Going under is easier. With funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, we’re able to look at fence location and wildlife movement data to plan and coordinate a highly targeted on-the-ground strategy for fence mitigation. In this way, our project can have a clear and tangible impact on connectivity for not only pronghorn but a diversity of wildlife species.

Collaboration is key

A really important aspect of this work is that it’s not about pointing fingers and accusing folks of having “bad” fences. Instead, it’s an excellent opportunity to have a much-needed conversation about what is practical for both wildlife and people. It’s likely that wildlife-friendly fences won’t work everywhere. But surely there are locations on any given ranch in the West where fences can be modified to ease passage for wildlife while still doing their job of holding in livestock. So, it’s a matter of finding them. In addition, there’s an opportunity to include fencing in larger connectivity plans and proposals that might also include roads, railroads, and other linear features restricting movement.

Wildlife are savvy, and though they can figure out ways to navigate the complex matrix of human development, there’s immense opportunity to make life easier on them. The data from the GPS collars tells us that, on average, pronghorn interact with a fence about every 1.3 miles along their 80-mile trek from their winter range in Horse Prairie to their summer pastures of the Mount Haggin Wildlife Management Area. That’s over 120 fence crossings on a round-trip journey.

Remote cameras are showing us that many pronghorn have back injuries from crawling under low wires, and this can lead to infection and stress. In my experience so far, I’m finding that nobody wants to see that. Better still—as I discovered working with ranchers, volunteers, and other agencies—people are motivated to do something about it. It is estimated that we’ve lost over 75% of historic long-distance terrestrial migrations in the contiguous US, and so it’s our responsibility to caretake the land and the wildlife in a way that can sustain those that remain.

There’s a lot more work to be done and I am inspired by the folks who are eager to get out on the landscape and make a positive impact for wildlife. We’re planning to improve at least 16 miles of fences by 2024 in the Horse Prairie area and Big Hole valley, and there’s a significant opportunity to scale-up this work. This summer, I was impressed by how many volunteers already realize the importance of increasing landscape permeability to sustain wildlife migrations. That’s why they showed up. But I am also grateful to have folks out lending a hand who may have never given fences a second thought, until now.

Interested in volunteering? Please contact buzzards@nwf.org.