We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

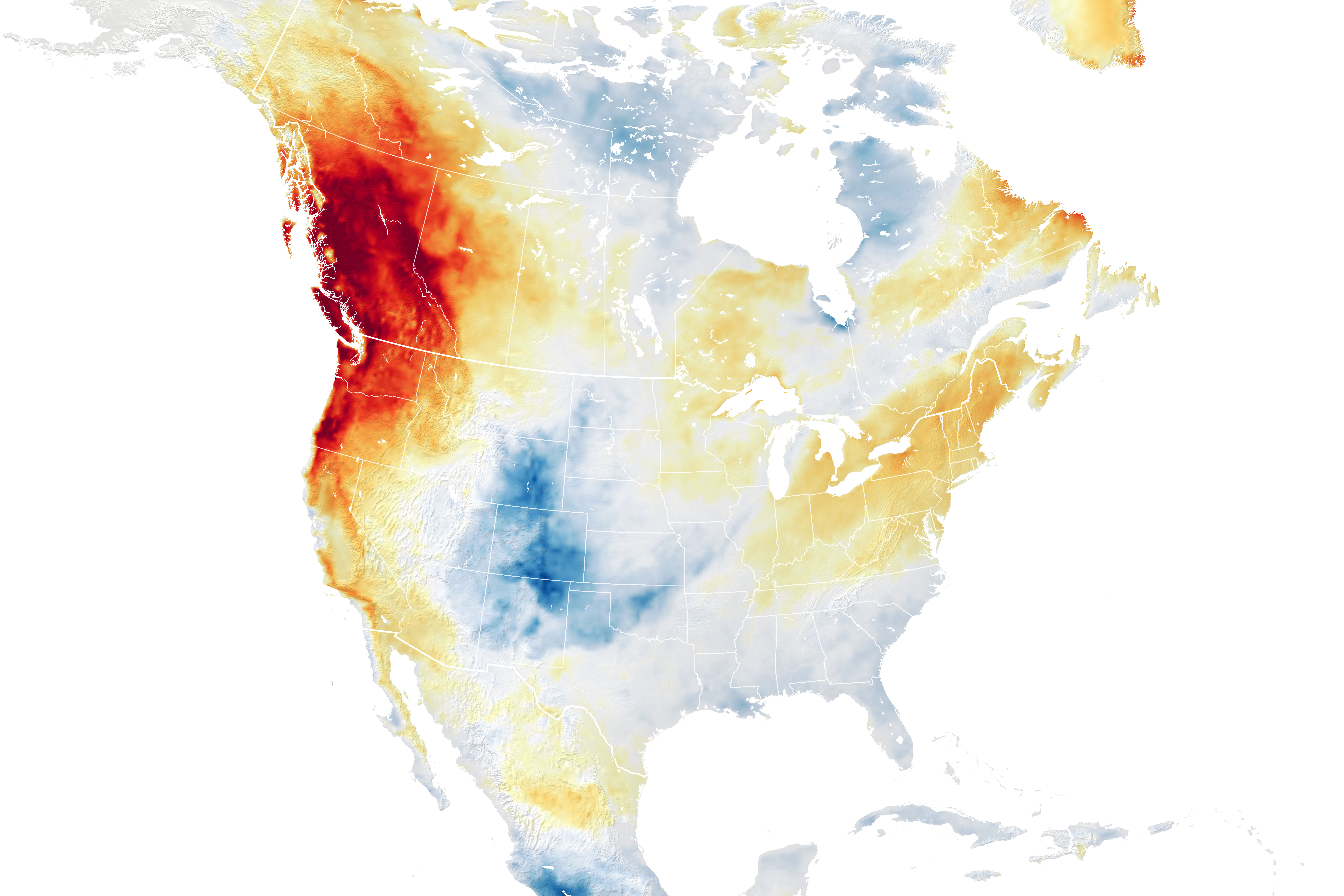

Last Summer’s Heat Dome Effects Were Frightening–and They Aren’t Over

Long term consequences predicted to occur near the Columbia River and beyond

During the summer of 2021 millions of people in the Northwest were trapped in their homes, desperately seeking cool temperatures in the absence of air conditioning. As many of us suffered the effects of high temperatures, a tragic 112 people lost their lives in heat-induced deaths in Washington.

The miserable effects of the heat lasted for a few days, but the long-term impacts, to regional residents and wildlife, are still unfolding.

The extreme heat came from two pressure systems—one from the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, and another from James and Hudson Bay in Canada. The Pacific Northwest became trapped in what is described as a “heat dome,” defined by the Columbia Riverkeeper’s community organizer Kate Murphy as “an area of high pressure that traps heat beneath it.”

“Essentially,” Murphy said, “the area of high pressure acts like the lid on a pot.”

In a place like the Pacific Northwest, where ecosystems rely on cooler temperatures, such extreme heat can have severe, cascading impacts, some of which we have yet to fully understand.

THE COLUMBIA RIVER SALMON—Cold water fish in hot water

The Columbia River Basin, a watershed that stretches from Canada through Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, was on the receiving end of the heat dome’s immediate impacts.

A video released by the Columbia Riverkeeper in mid-July shows sockeye salmon with dramatic lesions and fungus in the Columbia River.

Salmon can become stressed in water temperatures around 65 degrees Fahrenheit and above. The water temperature reached above 72 degrees in parts of Lake Washington Ship Canal for over a week following the heat dome.

Hoping to help the Snake River sockeye salmon in the last 300 miles of their migration journey, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration intervened in July of this past summer. A group of scientists manually removed the fish from the hot water and drove them to the hatchery in Eagle, Idaho.

The heat from the summer is a reminder of a tragedy in 2015 when a heat wave and drought led to 1.5 million juvenile fish deaths that year.

WHITE-TAILED DEER FELT THE HEAT, TOO

Salmon weren’t the only wildlife animals directly affected by the 2021 summer heat.

According to Megan Kernan, water policy manager for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, a drought that began in the spring of last year and continued through summer increased the prevalence of viruses such as epizootic hemorrhagic disease, which is often fatal to white-tailed deer. The dryness limited their watering holes to just a few drinkable areas, where deer congregated in large numbers—perfect conditions for the spread of this infectious disease, as more deer are exposed to the infected gnats that transmit the disease.

It was a difficult summer for the entire region. Many are wondering if the ripple effects will end there, or if the heat dome’s impacts will have long-lasting repercussions.

While the answer demands more research, experts in the field are able to provide us with some opinions.

“Our natural systems are generally resilient,” said the Columbia Riverkeeper’s community organizer Kate Murphy. “However, there are a number of significant stressors on our critical forests at the moment. I certainly hope the forests will recover brilliantly, but we cannot continue adding more pressure and expect the outcome to be a good one.”

In a recent analysis, climate scientists estimated that this heat wave was made 150 times more likely by human-induced climate change.

Kernan says that this hot summer is just the beginning of a pattern we’ll continue to see with the changing climate.

“This issue and these risks aren’t going away. I think it’s important for resource managers around the state to start thinking about how we can build more drought resilient ecosystems.”

An event like this, which is currently estimated to occur once every 1,000 years, is predicted to begin happening every 5 to 10 years if the world continues to warm at the rate that it is.

This likely won’t be the only heat dome we’ll witness during our lifetimes. Jacklyn Hancock, hydrogeologist and drought coordinator for the Washington State Department of Agriculture, believes that the state needs to make some structural changes to allow for easier research regarding long term impacts.

“This is something we’re talking a lot about at the state level,” Hancock said. “I hope that in Washington and throughout this country, we begin to put a little bit more weight on collecting research about (long-term impacts) so we can be better informed when we’re faced with this type of event in the future.”

“There is no time to waste,” Murphy said. “What we do now matters.”