We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Urban Water Providers Protect Water for Wildlife

Innovative partnerships in Utah improve ecosystems and benefit people

For over a century, the Wasatch Mountainous expanse of Little Cottonwood, Big Cottonwood, Parleys, and City Creek Canyons has served as Salt Lake City’s municipal watersheds, one of the oldest Public Water Systems in the western United States. These watersheds are the source of clean, accessible drinking water for more than 360,000 people in Salt Lake City and portions of Salt Lake County.

Behind the tap at your kitchen sink lies a story that weaves together the municipal water supply with the vast mountain range, the snow that it captures, and the essential habitat needed for fish and wildlife to thrive throughout the watershed.

History: A Legacy of Protection & Restoration

The Wasatch Mountains have long been an island oasis in the middle of a sagebrush sea. Many different Indigenous Tribes such as the Ute, Goshute, Shoshone, and Paiute have long found respite from the arid climate along the mountain streams. The Tribes have used the waterways as a major source of food with fish, plants, and wildlife that congregated around the waterbodies. The Ute relationship with and love of the land has tied their culture closely to the earth and its abundance. The Shoshone traveled with the seasons. They call the earth “Mother Earth” because all things, including food and shelter, come from Mother Earth. These Tribal Nations live in and steward natural resources across Utah today.[1]

In 1847, settlers arrived to the Salt Lake Valley. Soon trees were cut to help build the city below and shore up mines. Sheep and cattle grazed heavily, adding to the impact on water quality. (Figure 2. Early Issues – Post Mining – Alta). Spring “runoff” flu was soon prevalent as a result of the contaminated water.

The need to manage these watersheds to provide clean and reliable water was soon evident. To that end, the City and the state of Utah petitioned the federal government to create the Wasatch Forest Reserve. Set aside by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, the Salt Lake Forest Reserve’s main purpose was to provide drinking water to the communities in the valley below, with the additional benefits of biodiversity and providing habitat for native fish and wildlife. This launched a century-long partnership between the City and the U.S. Forest Service that turned the tide of environmental degradation and carefully stewarded these canyons back to ecological health.

Partnerships were critical to this rehabilitation. The City and U.S. Forest Service were assisted by the Civilian Conservation Corp as well as other eager partners. In addition, the nascent ski resorts purportedly used the small trees harvested in this work to craft their ski runs. As the outdoor recreation industry grew, so did the trees.

Stressors to Watersheds and Drinking Water

Fast forward a hundred years and, with challenges of the past met, our watersheds are now being severely challenged by the increasing demand from population growth, the accompanying outdoor recreation, climate change, and increased fire risks.

Catastrophic wildfire is one of the greatest threats to the Wasatch Mountain watersheds and drinking water, as in other municipal water supplies across the West. A century of wildfire suppression has created significant fuel build-up. The trees planted to restore the canyons lack age diversity within the forest community. Wave after wave of invasive insects and vegetation perpetuate fire risk. As a result, wildfire frequency, intensity, and duration have increased throughout the West over the last 50 years. The impacts on the watershed are significant and include erosion, landslides, flooding, and loss of precious habitat. This threatens a crucial source of drinking water as well as the integrity of fish and wildlife habitat throughout the watershed.

Fortunately, through collaborative restoration efforts and strategic investments, we can address these threats and improve watershed health, water sustainability, and wildlife habitat. For example, in Oregon’s McKenzie River watershed, a diverse partnership has worked to build fire resilience and restore landscapes impacted by increasingly intense fires.

Watershed Stewardship Partnerships and Collaboration

Salt Lake City has benefited from a long legacy of partnerships to manage our watersheds, from the US Forest Service, non-profit organizations, and government agencies, to ski areas, canyon residents, and the public. The City is also a partner of Utah Shared Stewardship, which works collaboratively with other public, private, and nonprofit organizations to address wildfire risk and water quality and quantity issues utilizing landscape-scale projects throughout the state. One such Shared Stewardship project is the Parley’s and Lambs Canyon Fuels Reduction Project, which received the 2021 Regional Forester’s Award. Just this year in In May 2022, Utah Gov. Cox and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack signed a renewed Shared Stewardship agreement that reaffirms a mutual commitment to building the relationships and coalitions needed to effectively confront the wildfire crisis throughout the state of Utah.

Working in this framework of Shared Stewardship, the City is presently working with the State, Salt Lake County, and the U.S. Forest Service on planning for watershed-wide fuels treatments. At present, the environmental clearance work is underway with multiple years of fuel treatments being planned. Public outreach is ongoing as the phases of fuel treatments are rolled out.

Watershed Planning and Education

Long-term planning is crucial for the successful protection of our watersheds and the drinking water they provide, as are updates to management plans.

The City’s Watershed Management Plan (WMP) serves to protect source water and guides our watershed policies while documenting how our source waters are protected. Once the update is complete, there will be recommendations to address growing issues like climate change, population growth, exploding recreational use, protection of wetlands, and habitat and wildfire risk. In addition, the WMP update will include a robust fire resiliency plan and climate change analysis. This plan will also inform the fuels reduction efforts in Shared Stewardship with a water quality focus. Importantly, the City hopes to support efforts to reduce the threat to homes, businesses, and life safety and also add a broader recognition of the need to protect the ecosystem services these canyons provide.

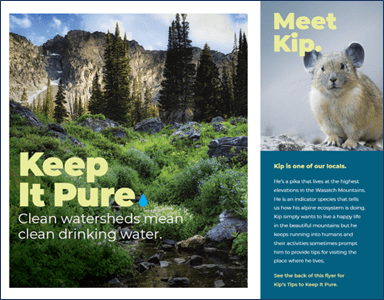

Often, the public is unaware of where their drinking water comes from and why it is so pure. This prompted us to relaunch our “Keep It Pure” Initiative to raise awareness about keeping watersheds clean. “We’ve learned a lot over the 150 years we have been managing and protecting our watersheds. Most importantly, we’ve learned that no one entity can do it alone. We rely on the help of our partners to keep our water pure, but no less important is our need for the public’s help,” said Laura Briefer, Salt Lake City Department of Public Utilities Director.

Compared to other areas in the country, where watershed areas for drinking water are closed to public use, we have a unique situation in the Wasatch Mountains. Much of our watershed lands are in publicly accessible national forests. Yet we have been able to provide affordable high-quality drinking water to our diverse community in the Salt Lake Valley and protect fish and wildlife habitats. This is in tandem with accommodating growing demands for recreation.

Aligning these community values requires a balanced approach using a combination of strategies, factoring in climate change and wildfires. We will continue balancing these community values and our legacy of long-term stewardship of these watersheds for future generations.

The innovative partnerships supporting watershed health and resilience in Utah’s Wasatch Front are part of a trend emerging throughout the West. The National Wildlife Federation coordinates the Healthy Headwaters Alliance, a coalition including Salt Lake City Department of Public Utilities and other western water innovators, utility executives, federal land managers, scientists, community and water justice leaders, and conservation professionals, who share a commitment to equitable, science-based actions to build resilience back into western forested headwaters.

References

Cuch, Forrest S. History of Utah’s American Indians. Logan: Utah State University Press, 2003.

Duncan, Clifford. “The Northern Utes of Utah.” In History of Utah’s American Indians, 167-224. Logan: Utah State University Press, 2003.

Parry, Mae. “The Northwestern Shoshone.” In History of Utah’s American Indians, 25-72. Logan: Utah State University Press, 2003.

[1] Cuch, History of Utah’s American Indian; Duncan, The Northern Utes of Utah, 67-224; Parry, “Northwestern Shoshone.”