We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Follow the Water: Natural Solutions for Wildlife and People Along the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River touches 10 states along its 2,300-mile-long path and drains an area encompassing all or parts of 31 states and two Canadian provinces. Nearly 20 million people rely on the river for daily drinking water. The Mississippi River basin is the migratory flyway for 60% of North America’s bird species. The river also supports a billion-dollar shipping industry and over a million jobs.

But climate change and river management over the decades have led to wild swings between floods and droughts. The loss of wetlands, grasslands, and forests in the basin harms water quality, worsens these flood and drought cycles, and impacts fish and wildlife. Invasive species disrupt aquatic ecosystems, while pollution from industrial agriculture threatens drinking water, wildlife, and creates a large dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

Protecting and restoring our nation’s largest watershed is no small feat. What would it take to create large-scale change?

NWF and our partners are working with nature to find ways to improve the quality of life for communities all along the Mississippi River.

We champion ‘nature-based solutions’ that incorporate natural systems in projects that benefit communities, such as restoring wetlands to reduce flood risk, increasing sustainable agricultural practices to enhance water quality, and improving system hydrology to increase wildlife habitat and watershed resilience.

Right now, we are focusing on three places along the Mississippi River that are facing very different challenges. By diving into these specific places, we’ll learn more about how to harness the power of nature to solve big problems, and hopefully, to create a body of knowledge we can use elsewhere in the basin–and around the country.

Building a safer future for the Quad Cities

The challenge at hand: As climate change intensifies, extreme weather–including flooding, droughts, and high temperatures–will affect the quality of life in river communities like the Quad Cities of Iowa and Illinois. The Quad Cities region faces unique threats due to the Mississippi River mainstem and several large tributaries upstream, like the Rock River, that play a role in local flooding. Furthermore, the bi-state, multi-city region presents distinct planning challenges.

Zoom in: Our new climate assessment summarizes the risks posed by climate change and explores ways to mitigate these risks.

The big picture: We’re collaborating with local stakeholders to determine the most effective and beneficial strategies for climate resilience that strengthen ecosystems and communities across the Quad Cities, including communities upstream of the urban center.

Letting West Tennessee Rivers Flow Freely

The challenge at hand: All but one of the rivers in West Tennessee were channelized in the middle of the last century, leaving a marred landscape, with poor water quality and with rivers and streams largely disconnected from both floodplains and groundwater.

The channelization of these rivers triggered a public backlash in the 1970s that ultimately led to a statewide “no channelization” policy. This policy led to the eventual creation of the West Tennessee River Basin Authority, a pivotal entity tasked with restoring the natural flow and function of West Tennessee rivers. However, increased flooding and rapid urbanization continue to threaten the communities and habitats of West Tennessee.

Zoom in: NWF and partners with the Tennessee Wildlife Federation and The Nature Conservancy are working to restore the natural flows of West Tennessee’s rivers through nature-based solutions such as restoring floodplains, wetlands, and the natural meander of streams that will reduce floods and protect communities.

The big picture: Channelized rivers are not unique to Tennessee; rivers and streams in western Kentucky are also largely channelized and the floodplain forests are now converted to agriculture and other uses. The work in West Tennessee can influence integrated floodplain management efforts elsewhere in the basin.

Exploring Hydrology in Eastern Arkansas

The challenge at hand: Our nation has lost 60 percent of its original bottomland hardwood forests. Arkansas contains some of the largest and most intact stretches, though those acreages are rapidly declining. In Eastern Arkansas, where river management and land use changes have altered hydrology, we are investigating ways to restore original stream flows, safeguard at-risk communities, and preserve wetlands.

Zoom in: Protecting and restoring bottomland hardwood forests through water management and other natural solutions will reduce flooding, improve water quality, and sequester carbon while providing important habitat for migratory waterfowl and songbirds. We’re working alongside partners, like sportsmen, as duck hunting plays a vital role in the region’s economy.

The big picture: With the Arkansas Wildlife Federation, NWF is exploring how enhancing the way water is managed in eastern Arkansas can improve bottomland hardwood forests and the quality of life for communities.

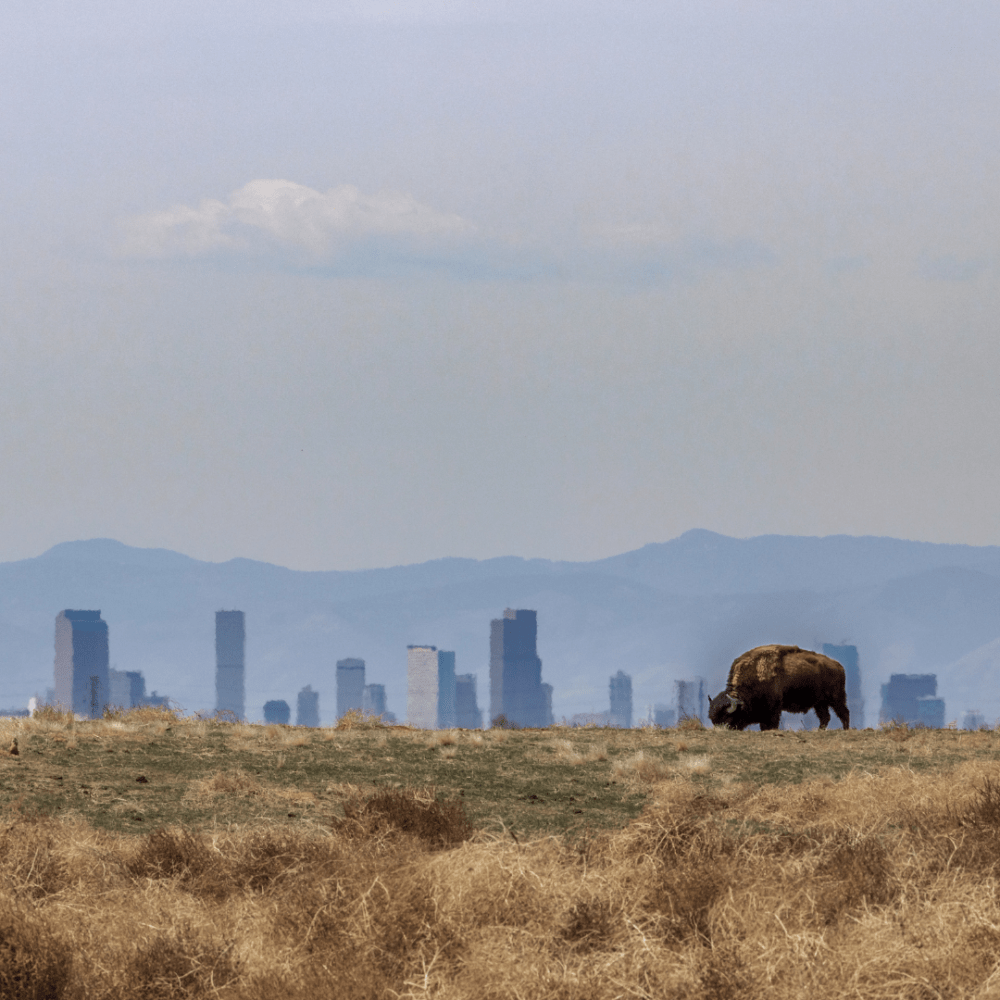

Building Momentum: What’s Next for Beaver Conservation in Colorado