We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Talking Snake River Salmon as Spring Approaches

This is shaping up to be an active year for the Snake River, its dams and its salmon.

There could be extra water spilling through the dams on the lower Snake and lower Columbia Rivers this spring to help juvenile salmon get downstream – unless last ditch efforts by the Corps of Engineers thwart agreements reached by federal, state and tribal biologists to provide more water for fish.

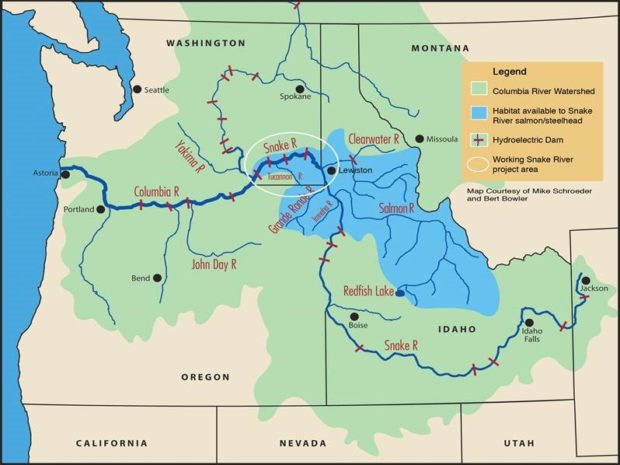

The increased amounts of spill were ordered by federal district court Judge Michael Simon as an interim measure while federal river agencies work through a five year process to look at how wild salmon and steelhead runs in the Columbia and Snake can be restored. Specifically on the table is the option of breaching the four dams on the lower Snake River. Not content with the collaborative agreement for interim spill that was signed off on by federal biologists, the Corps is seeking immediate review form the Ninth Circuit in yet another attack on restored threatened and endangered runs of fish.

To highlight both the progress that has been made and the big challenges that remain for restoring wild salmon and steelhead, the Save our Wildlife Salmon Coalition, which includes the National Wildlife Federation, decided it was time to talk to the public.

The groups invited two reporters well versed in all things salmon to talk about the Snake, which flows through Idaho into the Columbia, and the Elwha River on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula.

Rocky Barker of the Idaho Statesman, and Lynda Mapes, reporter for The Seattle Times, did double duty the week of January 21, presenting “A Tale of Two Rivers” to standing room crowds in Seattle and Spokane.

Barker spent 2017 reporting and writing a series of stories on the Columbia River, salmon and power. He was the lead researcher on editorials that called for breaching four Snake River dams to save salmon. He is the author of the book “Scorched Earth: How the Fires of Yellowstone Changed America.”

Mapes covered the removal of two dams on the Elwha and has written about what has happened to the river and the land around it since the dams were breached. Her book, “The Elwha, A River Reborn,” grew out of her reporting.

“Now you can stand in the former reservoir and there are trees over your head,” Mapes told the Seattle audience. Two dams blocked the river for 100 years, until the Elwha dam came down in 2011 and the Glines Canyon Dam followed in 2014.

Natural recovery behind the former dams is going to take 20 years, she said, and the salmon recovery won’t be a steady one. The number of fish returning to the river this year and next will be down from the first few years after the dams were breached. That’s because the fish returning now traveled down river when sediment built up behind the dams was being flushed from the river.

The recovery is about more than salmon though, Mapes said. As the habitat is restored, other species – from insects to elk – are thriving.

In 2010, the Elwha dams came up for license renewal and were found to be operating below current power production efficiency standards, which led to their removal.

That won’t be the case with the dams on the lower Snake River. Construction on the four dams lasted from 1962 to 1978, and they still provide power, Barker said, although they are not as important to the power grid as they were 20 years ago.

They also provide water to irrigate wheat and make it possible for barge traffic to carry it away.

But Barker said the river “doesn’t produce the goods and services like it did 20 years ago.” There are fewer farms pumping water out of the river and less barge traffic. As for power, these dams were always the lesser lights in the Columbia-Snake power system.

Barker said that Idaho, unlike on the Elwha, has habitat that doesn’t need to be restored.

“We still have water. We still have habitat. We have to decide what we’re going to do with them.”

The process of deciding has been going on in federal court since 2001 when the National Wildlife Federation and other plaintiffs brought a lawsuit against federal agencies to force them to abide by the Endangered Species Act and protect salmon in the Columbia River basin. That was not quite 10 years after Snake River sockeye were listed as endangered.

In April 2017, Judge Simon ordered plaintiff and defendants in the lawsuit to work together on a plan for how much water could be spilled over four dams on the Snake and four dams on the Columbia to improve the survival rate of young salmon heading downriver. The result is a plan to start in April for flows to be as large as they can be under Washington and Oregon’s limits on dissolved gas. High concentrations of dissolved gas can be harmful to young salmon.

“Every time spill is increased, salmon returns also increase,” said Tom France, Executive Director of the National Wildlife Federation’s Northern Rockies, Prairies, and Pacific Regional Center. “The increased spill order by the Court should lead to this same positive result.”

But it won’t happen if government attorneys get their way. They have appealed the judge’s order that resulted in the increased spill operation.

“It is truly unfortunate that the Corps of Engineers continues to fight real progress for fish even when their experts participated in the solution,” France wrote in an email.

Beyond the immediate increases spill ordered for this spring, Judge Simon has also directed the federal agencies to come up with a new biological opinion and analysis on how they’re going to protect and recovery endangered fish. Under the Judge’s order, the agencies must consider breaching the four lower Snake River dams in this process and reach a new decision by 2021.

Since 2000, the federal river management agencies has issued four different biological opinions on how salmon and steelhead can be protected. Four times, federal judges have determined these proposals to be wholly inadequate. As one judicial opinion described it, the federal agencies continue to offer “relatively small steps, minor improvements and adjustments” when drastic action was called for.

“Nature is going to talk,” Mapes said. “I wonder if we are going to listen.”