We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Using Fire to Fight Fire

How “beneficial burns” are helping forests, wildlife and people adapt to a changing world.

2024 has been yet another brutal wildfire season in the United States, with 8.1 million acres burned so far this year. This is no coincidence—warmer, drier conditions resulting from climate change are resulting in larger and more severe fires, particularly in the western United States.

As threats increase to communities and wildlife in the path of these fires, many people in the U.S. are grappling with what they can do to mitigate their impact. Fortunately, in recent decades, once-overlooked ideas about fire have begun to make a comeback. Long practiced by Indigenous communities, Western scientists and forest managers are increasingly embracing periodic, low-intensity fire—“beneficial burning”—to reduce the severity of larger wildfires while benefiting a wide array of ecosystems in the process.

Fire as a Force for Good

The idea of “beneficial burns” might seem counterintuitive at first. Don’t fires destroy everything in their path? How can this possibly help plants and animals?

Fires, it turns out, are a natural part of many ecosystems. Many wildlife and plants have evolved to depend upon and benefit from occasional, lower-intensity burns. Indigenous peoples have harnessed this power for thousands of years using cultural burning, which involves intentionally setting smaller fires as a way to steward ecosystems and provide various cultural services. But over the past few hundred years, aggressive fire suppression policies implemented by European settlers prevented even low-intensity fires from blazing naturally, and cultural burning was criminalized in many areas.

By the mid-20th century, Western scientists began to appreciate fire’s integral role in many ecosystems. A growing number of land managers are eschewing fire suppression when natural blazes occur, instead simply allowing wildfires to burn in areas where lives and properties are not at risk. Indigenous land stewards, once largely sidelined, are reviving traditional practices.

And US government agencies now conduct “prescribed” or “controlled” burns on over 6 million acres each year, under strict precautions that ensure more than 99.8 percent of Forest Service burns go according to plan.

Beneficial Burning in Practice

This interactive map shows just a few examples of how beneficial burns are now used to reduce wildfire risk and support wildlife:

Longleaf pine ecosystems in the Southeast

In the southeast’s Coastal Plains region, one of the world’s global biodiversity hotspots, open forests of longleaf pine harbor a unique array of plants and animals. Once spanning more than 90 million acres, this ecosystem reached a historic low of around three million acres. The reintroduction of fire, which historically crept through the longleaf understory as often as every two to five years, has helped bring the total area to more than five million acres.

Prescribed burn associations can catalyze learning and offer private landowners opportunities to apply beneficial fire in their own forests and woodlots.

Oak woodlands

Oak trees are some of North America’s keystone species, providing food and habitat to many animals. With their thick bark and ability to resprout, oaks can survive fire, and their flammable leaves even help to promote low-intensity burns.

Before European settlement, some oak forests and woodlands saw fire every three to 20 years, but fire suppression in recent decades has created conditions that now make it hard for young oaks to grow. The reintroduction of fire can help: Efforts such as the “Ready-Set-Fire in White Oak Woodlands” project in southern Indiana are funding beneficial burns on both public and private lands, helping to give declining white oak forests a boost.

Ponderosa pines in the Mountain West

One of the iconic trees of the Rockies, ponderosa pines can be found in dry, high-elevation forests from Canada to Mexico. Like many pine species, ponderosa pines are adapted to periodic fire. Historically, fire returned around once every five to 25 years, clearing out understory vegetation and young trees while leaving many mature trees unharmed.

Fire suppression, on the other hand, leaves ponderosa pines vulnerable to overcompetition, drought stress, and insect damage. Today, forest managers periodically burn ponderosa pine stands—such as in Utah’s Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest—to promote forest health and to prevent the spread of larger wildfires.

Pitcher plants in Florida

You may not associate Florida wetlands with wildfires, but much of its unique biodiversity has adapted to occasional burns. One example is carnivorous pitcher plants, which use nectar and a uniquely tube-shaped structure to attract and trap insects. These unusual plants thrive best in wet prairies, often those that have been recently burned, where they aren’t crowded out by larger trees and shrubs. In recent years, biologists and land managers at locations such as Deer Lake State Park have used burns to clear overgrown areas and help create the conditions for pitcher plants to thrive.

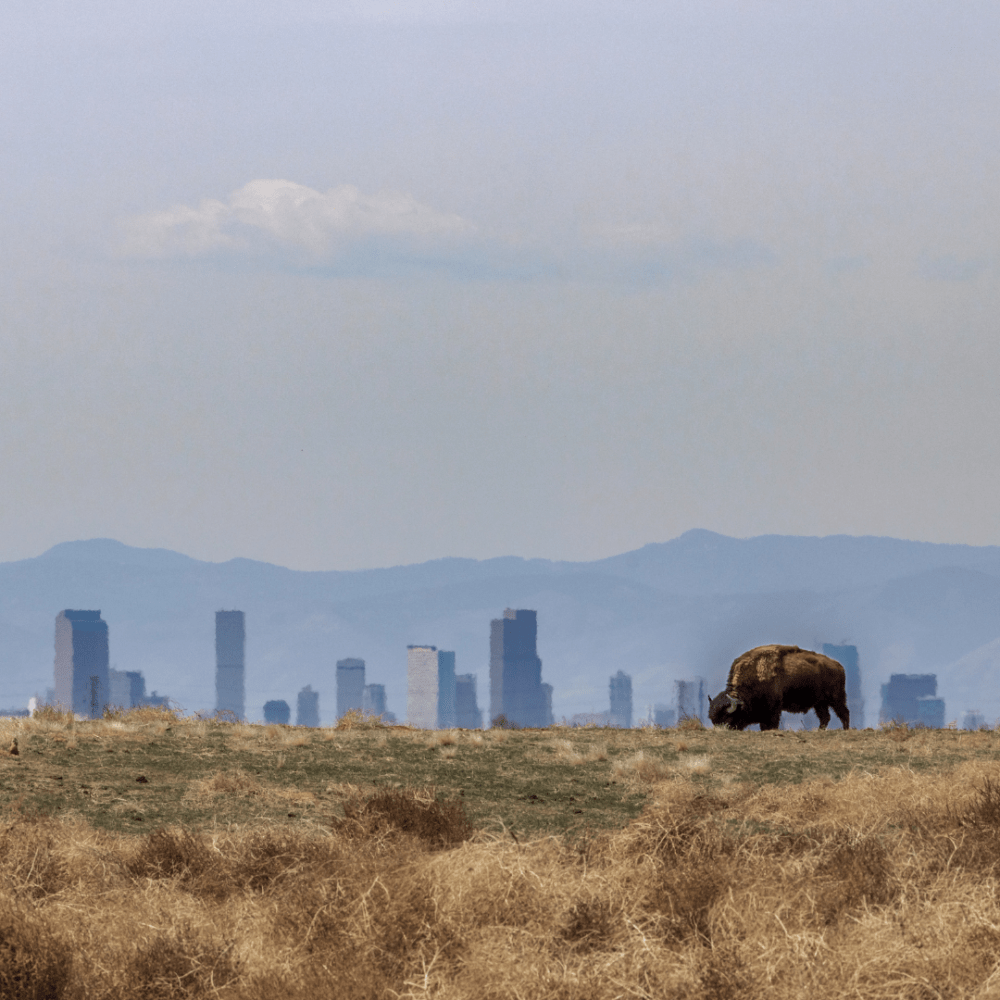

Grasslands in the Great Plains

Wild grasslands are one of America’s most threatened ecosystems, currently vanishing as fast as the Brazilian rainforest. And while many identify agricultural development as a primary culprit, fire suppression has played a key role too. Without periodic fire to clear out young trees, some grasslands effectively transform into forests over time, a process known as “woody encroachment.”

Increasingly, Plains States landowners are using burns to resist ongoing encroachment. A landowner’s alliance in Nebraska formed in 2002, for example, has used fire to reclaim nearly 90,000 acres of prairie habitat to date. These efforts have a wide range of benefits, from seed dispersal to soil enrichment to invasive species control, and are an equally critical tool in reducing wildfire risk.

With wildfires blazing across many of our cherished lands, it’s hard to see fire as anything more than an enemy. In fact, when harnessed strategically, it’s one of our most powerful tools in a broader suite of actions that can enhance resilience for forests and other ecosystems.

As climate change pushes the natural world to its limits, it’s more important than ever to use our best available tools to help forests adapt. By embracing beneficial burns, we can reduce wildfire risks and restore the historic bond between people, fire, and land—a bond that has sustained ecosystems for centuries.

To learn more about NWF’s work to engage communities in the Southeast, click here.